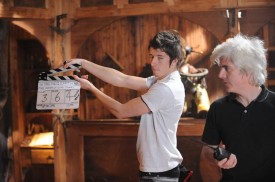

Col constantly ribs me about the lack of a first assistant director on Stop/Eject, and the consequent lack of adherence to the schedule. But as I edit the film, I’m appreciating more and more the other duties of a first AD and the consequences of those duties going undischarged.

Because part of the first’s job is to literally assist the director – to help them keep track of things which can easily get forgotten amidst the chaos of filming. Things like crossing the line, getting enough coverage and not missing out bits of the script. (Two other crew members that a big budget production will have who will also be looking out for those things are the script supervisor and the editor – because the editor will be cutting the material the day after you shoot it, and may be able to tell you before you leave a location that you need an extra shot.)

So here are some examples of the moronic cock-ups I made, which might well have been avoided if I’d had a first and/or a script supervisor looking out for me:

- Tommy Draper wrote a great stage direction in one scene: “She opens the fridge. It’s as empty as her life.” Unfortunately I chose to shoot it in a way that made it impossible to tell the fridge was empty, because I didn’t pay close enough attention to the script during filming.

- In another scene, I wrote that the cellophane is torn off an object before it is used. I included that detail in the script because, as a writer, I knew that otherwise the audience would not necessarily understand the important point that the object was brand new and unused. Somehow this got dropped from the scene during rehearsals, and it wasn’t until I saw the film edited together that I realised how crucial the cellophane was.

- In scene seven, the most complex of the film, we decided during rehearsals to alter the timing of an incident. One side effect of this – which again I didn’t notice until I saw the edit – was that the shots I had storyboarded (and thus the shots that I filmed) no longer established satisfactorily the whereabouts of one of the characters at a critical moment.

- In scene 24 I crossed the line. You can see this at the very end of the trailer.

The omission of things in the script are particularly annoying (a) because I co-wrote the bloody thing and should have noticed, and (b) because any good writer takes care to be economical with words and only put in things which are important.

Some of these things can be fixed with pick-ups. For example, I filmed a close-up of my wife’s hands unwrapping the cellophane in our flat recently. But others have no solution beyond a major reshoot, which would be very hard to justify. So what you end up with is a subtle erosion of the quality of the film, and this is one of the reasons that a more expensive film looks more expensive. A bigger crew does mean more attention to detail and thus higher production values in every respect.

I share these thoughts with you not because I’m any less proud of Stop/Eject or feel like I need to make excuses for it, but simply to pass on a lesson the project has taught me. It’s very easy to think of a first assistant director as merely a time-keeper, but if you work without one you should appreciate that there are other strings to their bow, and your project may suffer more lasting effects than just a tired cast and crew.