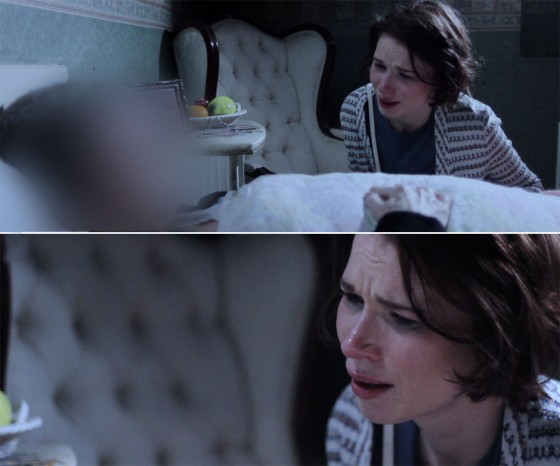

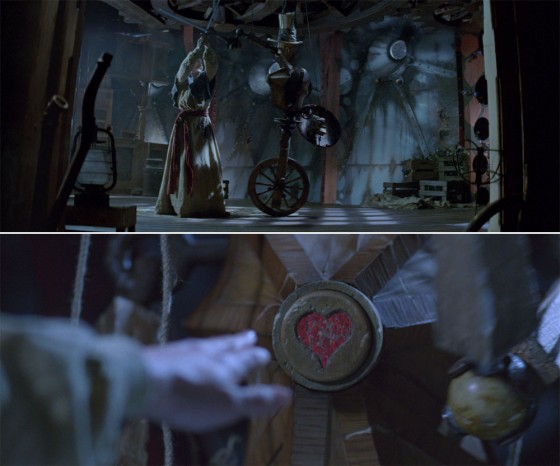

Tomorrow the film I’m currently DPing, The Deaths of John Smith, has an extremely packed schedule. This has got me thinking about how a filmmaker can keep themselves on schedule when faced with a seemingly impossible amount of material to get through.

The most effective action is of course to take out a big red pen and start cutting down the script. I know personally I find this very difficult, particularly if I’m both the writer and the director, because I’ve convinced myself by this point that everything in my shooting draft absolutely has to be there. Even though I know that, when I get to the edit, some scenes will inevitably get deleted and some dialogue will get trimmed. The challenge is to identify those trims now, on set, and save myself the trouble of shooting them.

Beware that simply cutting some dialogue is unlikely to have a signficant effect on your schedule, because most of your time on set is spent not shooting or even rehearsing, but setting up. Take a long, hard look at your shotlist or storyboards. Do you really need all that coverage?

Consider a Single Developing Shot (SDS). This means shooting an entire scene in just one set-up, with some camera movement and perhaps some dynamic blocking to maintain interest. The danger here is of doing a ridiculous number of takes of this one set-up because you know you have nothing to cut to if it’s not perfect (a trap I’ve fallen into more than once). I would advise qualifying your SDS with a cutaway or two to claw back a bit of flexibility in the edit and ease the pressure on the master shot.

If you can’t see a way to reduce the number of shots you need, consider ways to make those shots quicker to film. The most time-consuming shots for a director of photography to light are reverses, where the camera flips around to shoot in the opposite direction to all the previous angles, meaning every light has to be moved, along with the video village and all the piles of idle equipment in the background. Can you get away without a reverse, by changing the blocking a little? That character who has their back to camera – could they cheat their profile towards us a bit? It’s cheesy and not very realistic, but TV shows often achieve this by having one character talk to another’s back.

Down-the-line close-ups are also quick to do. This means that, after doing your wide, you leave the camera more or less where it is (and, crucially, the lights too) and put on a longer lens to get your close-ups. Watch your continuity carefully, because down-the-line cuts will really show up any errors.

If all else fails, the wrap time is looming and you’ve still got half a dozen set-ups to get, it’s best if those set-ups are close-ups or even cutaways. Because you and a skeleton crew can come back another day, maybe to a different location, maybe with a stand-in for your lead actor, and shoot tight pick-ups. Clearly this isn’t going to work with a wide master shot, for which you would need your whole cast and crew back, and the same set/location.

Finally, when working as a DP I have occasionally been asked to speed up the shoot by not lighting it. It is usually at this point that I feign hearing problems. Yes, not lighting stuff will speed up the shoot enormously. But you’re no longer making a professional film; you’re making a home video with an expensive camera. Don’t ask your DP to do this – you’ll only offend them. Instead, perhaps ask what camera angle would require the least re-lighting.

What tricks and techniques have you used to speed up your shoots?