Can a scene be lit with just one lamp? It certainly can, and in fact some of cinema’s most stunning and iconic images have been achieved this way. A single source image can be realistic or stylised, flattering or scary, but is almost always arresting. Even if you decide the look of a single source is too extreme, and add more lamps, building the lighting around that one key source can still be a very useful approach.

Let’s consider some of the ways in which a single source can be used.

Front Light

Front light is not very common in cinematography because – and this will be especially true without any other sources – it produces a flat image. Often we think of front light as being devoid of depth, though in fact it does reveal depth because things closer to the camera (and therefore also closer to the light) are brighter, while distant backgrounds are darker. An example is the sequence from Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind in which the frontal spotlight and the resultant dark surroundings represent the protagonist’s memories being erased.

More common is three-quarter front light, which gives some modelling on the face, and is consequently seen a lot in portraiture, both modern and classical.

Side Light

Light from the side can be the most informative, revealing shape, texture and detail. As a single source, it produces incredible chiaroscuro – contrast between light and shade. This shot from the The Godfather is a great example.

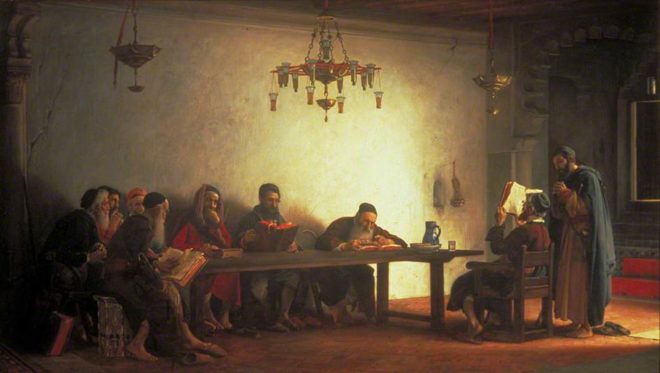

Here is a more complex example from classical art. I saw this painting at the Guildhall recently and it inspired me to write this post. I love the way that the soft light comes in through an unseen doorway to the right, illuminating the wall and modelling each of the people differently according to the angle it reaches them at.

Toplight

Perhaps the most famous use of toplight is in The Godfather‘s opening scene, where the characters’ eye sockets are rendered black and hollow by the steep angle of the single source.

A ceiling lamp hanging over a table is one of the most frequently seen examples of single source top-lighting.

Often the table or things on it – papers, white tablecloths – will reflect back some of the toplight, filling in the shadows. Film Riot investigates the many variations of this set-up in their episode on single source lighting.

Backlight

There are many examples of scenes lit only from the back. It’s a beautiful look, creating mood and mystery, revealing form without details, reducing people to simulacra. The optional addition of smoke helps the light to wrap a little and lift the shadows.

It’s not uncommon for a DP to begin lighting by setting a backlight to give form and depth to the scene, then seeing if and where other sources are necessary, to illuminate faces and other important details.

OMNIDIRECTIONAL

Most film fixtures shed their illumination in broadly one direction, but of course most light sources in day-to-day life aren’t that discriminating, throwing rays all around them. In the form of practicals, such omnidirectional lights can create very interesting images, particularly when they are handheld.

When people are grouped around an omnidirectional source, each one is modelled differently. Characters in the foreground, between the lamp and the camera, become silhouettes, while those to the sides are rendered in chiaroscuro, and those in the background are lit frontally. This creates a wonderful feeling of dark-to-light/near-to-far depth and dimensionality. 17th century Dutch masters like Gerrit Dou and Gerard van Honthorst painted such effects beautifully.

Having recently re-equipped myself with a 35mm SLR, I’m planning a photography project inspired by some of these candlelit scenes. Watch this space!