Two years ago I made Stasis, a series of photographs that explored the confluence of time, space and light. Ever since then I’ve been meaning to follow it up with another photography project along similar lines, but haven’t got around to it. Well, with Covid-19 there’s not much excuse for not getting around to things any more.

So I’ve decided to make a zoetrope – a Victorian optical device which produces animation inside a spinning drum. The user looks through slits in the side of the drum to one of a series of images around the inside. When the drum is set spinning – usually by hand – the images appear to become one single moving picture. The slits passing rapidly through the user’s vision serve the same purpose as a shutter in a film projector, intermittently blanking out the image so that the persistence of vision effect kicks in.

Typically zoetropes contain drawn images, but they have been known to contain photographed images too. Eadward Muybridge, the father of cinema, reanimated some of his groundbreaking image series using zoetropes (though he favoured his proprietary zoopraxiscope) in the late nineteenth century. The device is thus rich with history and a direct antecedent of all movie projectors and the myriad devices capable of displaying moving images today.

This history, its relevance to my profession, and the looping nature of the animation all struck a chord with me. Stasis was to some extent about history repeating, so a zoetrope project seemed like it would sit well alongside it. Here though, history would repeat on a very small scale. Such a time loop, in which nothing can ever progress, feels very relevant under Covid-19 lockdown!

With that in mind, I decided that the first sequence I would shoot for the zoetrope would be a time-lapse of the cherry tree outside my window. I chose a camera position at the opposite end of the garden, looking back at my window and front door – my lockdown “prison” – through the branches of the tree. (The tree was just about to start blooming.)

The plan is to shoot one exposure every day for at least the next 18 days, maybe more if necessary to capture the full life of the blossom. Ideally I want to record the blossom falling so that my sequence will loop neatly, although the emergence of leaves may interfere with that.

To make the whole thing a little more fun and primitive, I decided to shoot using the pinhole I made a couple of years ago. Since I plan to mount contact prints inside the zoetrope rather than enlargements, that’ll mean I’ve created and exhibited a motion picture without ever once putting the image through a lens.

To make the whole thing a little more fun and primitive, I decided to shoot using the pinhole I made a couple of years ago. Since I plan to mount contact prints inside the zoetrope rather than enlargements, that’ll mean I’ve created and exhibited a motion picture without ever once putting the image through a lens.

I’m shooting on Ilford HP5+, a black-and-white stock with a published ISO of 400. My girlfriend bought me five roles for Christmas, which means I can potentially make ten 18-frame zoetrope inserts. I won’t be able to develop or print any of them until the lockdown ends, but that’s okay.

My first image was shot last Wednesday, a sunny day. The Sunny 16 rule tells me that at f/16 on a sunny day, my exposure should be equal to my ISO, i.e. 1/400th of a second for ISO 400. My pinhole has an aperture of f/365, which I calculated when I made it, so it’s about nine stops slower than f/16. Therefore I need to multiply that 1/400th of a second exposure time by two to the power of nine, which is 1.28 – call it one second for simplicity. ( I used my Sekonic incidence/reflectance meter to check the exposure, because it’s always wise to be sure when you haven’t got the fall-back of a digital monitor.)

One second is the longest exposure my Pentax P30t can shoot without switching to Bulb mode and timing it manually. It’s also about the longest exposure that HP5+ can do without the dreaded reciprocity failure kicking in. So all round, one second was a good exposure time to aim for.

The camera is facing roughly south, meaning that the tree is backlit and the wall of the house (which fills the background) is in shadow. This should make the tree stand out nicely. Every day may not be as sunny as today, so the light will inevitably change from frame to frame of the animation. I figured that maintaining a consistent exposure on the background wall would make the changes less jarring than trying to keep the tree’s exposure consistent.

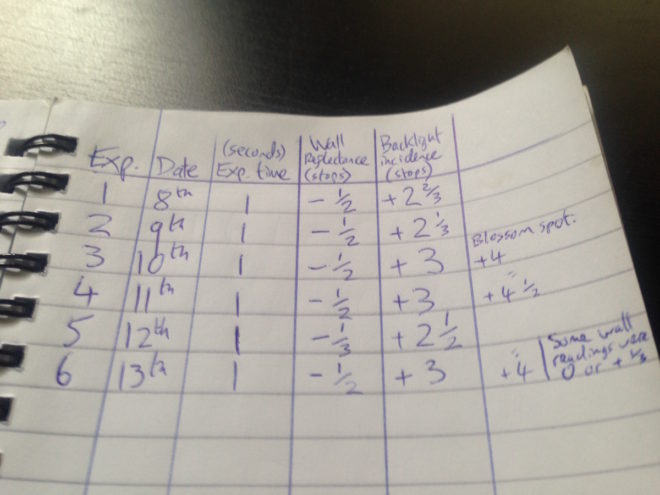

I’ve been taking spot readings every day, and keeping the wall three-and-a-half stops under key, while the blossoms are about one stop over. I may well push the film – i.e. give it extra development time – if I end up with a lot of cloudy days where the blossoms are under key, but so far I’ve managed to catch the sun every time.

All this exposure stuff is great practice for the day when I finally get to shoot real motion picture film, should that day ever come, and it’s pretty useful for digital cinematography too.

Meanwhile, I’ve also made a rough prototype of the zoetrope itself, but more on that in a future post. Watch this space.