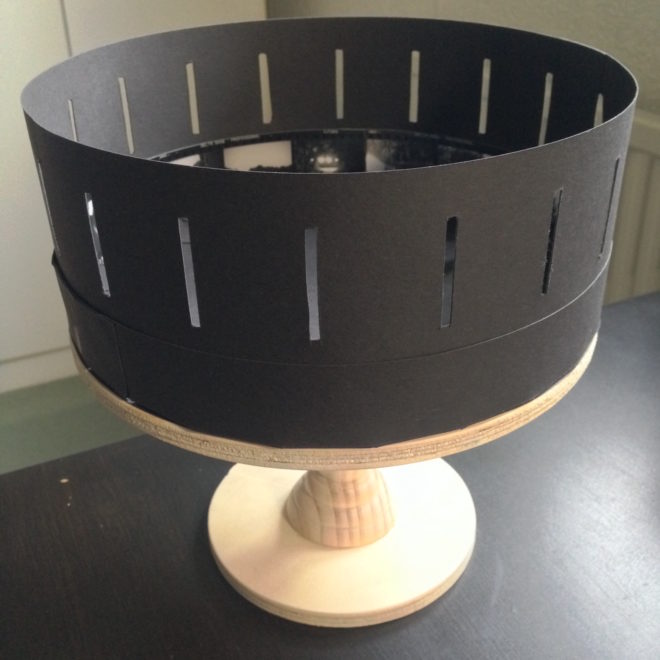

In the early days of lockdown, I blogged about my intentions to build a zoetrope, a Victorian optical device that creates the illusion of a moving image inside a spinning drum. I even provided instructions for building your own, sized like mine to accommodate 18 looping frames of contact-printed 35mm photographs. Well, last week I was finally able to hire my usual darkoom, develop and print the image sequences I had shot over the last five months, and see whether my low-tech motion picture system worked.

Making Mini Movies

Before I get to the results, let me say a little about the image sequences themselves and how they were created. Because I was shooting on an SLR, the fastest frame rate I could ever hope to record at was about 1fps, so I was limited to time-lapses or stop motion animation.

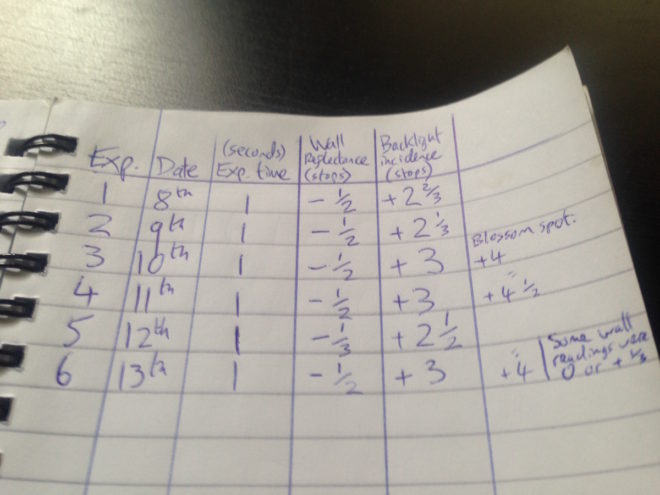

Regular readers may recall that the very first sequence I captured was a time-lapse of the cherry tree in my front garden blossoming. I went on to shoot two more time-lapses, shorter-term ones showing sunlight moving across objects during a single day: a circle of rotting apples in a birdbath (which I call Sundial), and a collection of props from my flatmate’s fantasy films (which I call Barrels). I recorded all the time-lapses with the pinhole I made in 2018.

The remaining six sequences were all animations, lensed on 28mm, 50mm or 135mm SMC Pentax-Asahi glass. I had no signficant prior experience of this artform, but I certainly had great fun creating some animated responses to the Covid-19 pandemic. My childish raw materials ranged from Blue Peter-esque toilet roll tubes, through Play-Doh to Lego. Orbit features the earth circling a giant Covid-19, and The Sneeze sees a toilet roll person sternutating into their elbow. Happy Birthday shows a pair of rubber glove hands washing themselves, while Avoidance depicts two Lego pedestrians keeping their distance. 360° is a pan of a room in which I am variously sitting, standing and lying as I contemplate lockdown, and finally Social Distance tracks along with a pair of shoes as they walk past coronavirus signage.

By the time I finished shooting all these, I had already learnt a few things about viewing sequences in a zoetrope, by drawing a simple animation of a man walking. Firstly I discovered that the slots in my device – initially 3mm in width – were too large. I therefore retrofitted the drum with 1mm slots, resulting in reduced motion blur but a darker image, much like reducing the shutter angle on a movie camera. I initially made the mistake of putting my eye right up to the drum when viewing the animation, but this destroys the shuttering effect of the slots. Instead the best results seem to be obtained with a viewing distance of about 30cm (1ft).

I could already see where I might have made mistakes with my photographed sequences. The hand-drawn man was bold and simple; it looked best in good light, by a window or outdoors, but it was clear enough to be made out even if the light was a bit poor and there was too much motion blur. Would the same be said of my 35mm sequences?

Postproduction

I contact-printed the nine photographic sequences in the usual way, each one producing three rows of six frames on a single sheet of 8×10″ Ilford MG RC paper. In theory, all that was left was to cut out these rows and glue them together.

In practice, I had managed to screw up a few of the sequences by fogging the start of the film, shooting a frame with bad exposure, or some other act of shameful incompetence. In such cases I had to edit much like filmmakers did before the invention of digital NLEs – by cutting the strips of images, excising the rotten frames and taping them back together. I even printed some of the sequences twice so that I could splice in duplicate frames, where my errors had left a sequence lacking the full 18 images. (This was effectively step-printing, the obsolete optical process by which a shot captured at 24fps could be converted to slow motion by printing each frame twice.)

Once the sequences were edited, I glued them into loops and could at last view them in the zoetrope. The results were mixed.

Barrels fails because the moving sunlight is too subtle to be discerned through the spinning slots. The same is partly true of Sundial, but the transient glare caused by the sun reflecting off the water at its zenith gives a better sense of motion. Blossom shows movement but I don’t think an uninitiated viewer would know what they were looking at, so small and detailed is the image. Orbit suffers from smallness too, with the earth and Covid-19 unrecognisable. (These last two sequences would have benefitted from colour, undoubtedly.)

I’m very pleased with the animation of Social Distance, though I need to reprint it brighter for it to be truly effective. You can just about make out that there are two people passing each other in Avoidance, but I don’t think it’s at all clear that one is stepping into the road to maintain a safe distance from the other. Happy Birthday is a bit hard to make out too. Similarly, you can tell that 360° is a pan of a room, but that’s about it.

Perhaps the most successful sequence is The Sneeze, with its bold, white toilet roll man against a plain black background.

Conclusions

Any future zoetrope movies need to be bold, high in contrast and low in detail. I need to take more care to choose colours that read as very different tones when captured in black and white.

Despite the underwhelming results, I had a great time doing this project. It was nice to be doing something hands-on that didn’t involve sitting at a screen, and it’s always good to get more practice at exposing film correctly. I don’t think I’ll ever make an animator though – 18 frames is about the limit of my patience.

To make the whole thing a little more fun and primitive, I decided to shoot using

To make the whole thing a little more fun and primitive, I decided to shoot using