It’s high time we heard from producer and production designer Sophie Black on this blog, so here are her thoughts on the pre-production of Stop/Eject.

Four days ago we wrapped on Stop/Eject after a six day shoot that felt like a month. There were stressful bits, and no one got much sleep. But it was also one of the best shoots of my life!

The footage is looking amazing (keep checking the Stop/Eject Facebook Page for all the stills as they come online) and I can’t wait for the trailer. This shoot, without a second’s thought, goes straight into my top two, and not just because I finally got to stay at home and film on my doorstep. My only problem now is that I’ve gone from working all day every day for about two months to an empty house and nothing on my immediate schedule. Cold turkey. So I’ve promised director Neil Oseman that I would start doing a series of guest blogs, and I hope that these will cure me of my Stop/Eject withdrawal symptoms.

Today I’m talking about pre-production in the Art Department, and for that I need to take us back to this time two weeks ago. Now, with all independent films – and particularly with short films – it’s to be expected that tasks will have to be shared out, and that job boundaries will get blurred as it’s all hands on deck. It is for that reason that two of the main set builders on all Light Films projects are the director and the writer, and that the catering on Stop/Eject was covered by the costume designer and the make-up artist.

So you expect to have to do work out of your job description. What you don’t always predict, however, is the workload that’s caused by drop-outs.

Two weeks before the Stop/Eject shoot, I had a pretty long list of work left to do. I was juggling the Ashes prep with last minute S/E casting, two rooms to paint and dress, a couple of props to finish, and over 400 tape cassettes to do calligraphy on (urgh!). Not an ideal amount of work with two weeks left to go, but achievable.

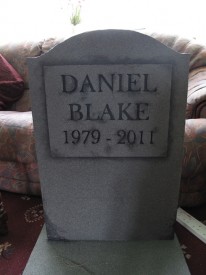

The first task was re-doing part of a gravestone set piece. Many things were rushed the first time we went to make Stop/Eject, and I’d had to make do with my first attempt, which was decent but a little untidy (first image below). The good thing about having to push back the shoot – although it was disappointing at the time – was the fact that we got to do everything a hundred times better. The gravestone was certainly one of those things.

To help me improve it, Neil got in contact with professional production designer Ian Tomlinson, who told me that I could get a neater finish on the lettering if I printed out a stencil then engraved it into foamboard. (I’d used polystyrene for the rest, which still made good stone).

After I stuck the foamboard over the original lettering, I spray-painted it with the same stone effect spray as before, left it to dry in my downstairs loo (there was nowhere else to put it!) then used a dry-brush in a darker colour to add ageing and definition to the lettering.

That went smoothly, and I managed to get the location painting done in one afternoon thanks to the help of a volunteer called Ellie Ragdale:

When you’re doing a job which isn’t paid, no matter how great the project, there’s always going to be someone who abandons it in favour of a wage. You can expect one or two at least. And when this happens, no matter how much you have on or how last minute it is, you can’t just turn round to the director on the day and say, “such and such isn’t here because the person dropped out,” or, “it wasn’t my job so I decided to put my feet up and ignore it”. Particularly when it’s part of your department (I was head of Production Design so anything to do with the decoration was supposed to be in my control). It can’t just be abandoned when the film needs it. Someone has to do it. And, much as I dreaded it, I knew it would have to be me. There was less than a week until the crew arrived and everyone was already juggling more than their fair share of jobs. I just had to crack on.

The first extra job I took on was the shop sign for the film’s main location. Because of the nature of my job I find it hard to trust helpers, and I rarely delegate on smaller tasks, but I knew a local craftswoman who made beautiful vintage signs so I asked her to do it. She would be paid, but she offered to do it for next to nothing, and I knew she would do a great job. Then I got a call saying that she’d had to go into hospital and wasn’t taking on anymore work.

This one certainly wasn’t anyone’s fault, and it wasn’t too huge a task, so I grabbed by brother’s old warhammer board and a paintbrush and made the sign. It was easy but it was frustrating because I knew that I wasn’t the best person for the job and, due to the other woman’s calibre, what I turned out could only be second-rate.

The next problem came when it was time to build the film’s all-important alcove set. We’d advertised for a builder and had a decent amount of replies, but some weren’t qualified, some didn’t respond to our replies, and others showed genuine interest in the job and sent us a couple of emails, then changed their minds. I managed to contact a few local people I knew and had a few offer to build it with my help, but out of them a few were busy on the day and a couple became oddly aloof and stopped replying to me. The only person left to help managed to stay long enough to help me fetch the materials I needed (thanks Steve!) but had to go at lunchtime due to a prior commitment.This left me, alone in my Dad’s cramped garage (moving into the kitchen for space when needed), with his power tools at hand but no will or clue. I’d only ever decorated a set before; I was trained to design them, even technically, but I’d never wielded an electric saw in my life!

But what I’ve learnt is that it’s amazing what you can do when you try. Luckily I only had to build a wooden box-type thing – albeit ones with panels made out of antique doors – and it wasn’t anything more complicated than that. Plus my Dad helped speed things up by cutting a few pieces after I’d measured and marked them.

Was that the last of the drop-outs? Of course not. We were supposed to have someone build us an ornate, carved wooden arch to go at the front of the alcove set. I’d given the guy the job then he’d sent me a quick concept sketch and I’d even spoken to him on the phone, where he sounded enthusiastic. With less than a week before the shoot, I called him twice to three times a day. every day, and even left him messages, but I never heard from him again. Although it was disappointing, this was one part of the set we decided we could do without.

Instead of two days, the set ended up taking five, during all of which I was thinking about the looming tape cassettes, and wondering when on earth I was going to get them done. My morale was also starting to get pretty low – the garage was cold and I was up until 1am every morning with only Soul Searcher and American Beauty on my laptop to keep me going.

In spite of the odds, by the time the crew arrived there were three completed sides for the alcove, all of which featured heavily-screwed wooden frames, antique doors, and stained hardboard surfaces. Just like that, I’d built my first set.

From that point onwards, I wasn’t alone anymore. The chivalrous Gaffer-turned-handyman Colin Smith built the roof for me, and made sure I had all the pieces I needed to make a basic wooden arch for the front. Then the lead actor Oliver Park joined in too, by staying up with me and helping me paint the last couple of pieces. He even played Aerosmith on his phone to keep me happy. It may be an old-fashioned sentiment, but I think that men are wonderful things!!

Thanks Sophie. I’m off to polish my crocodile shoes, but you can read more about Sophie’s work on her website.