When I read a script that I’m going to shoot, there are a number of things I’m looking out for. I want to identify the themes and the character arcs, so that I can come up with ways of reflecting these in the cinematography (see my previous blog post for examples). And on a more mundane practical level, I’m figuring out what equipment is required, and which scenes or sequences might be difficult photographically.

When I read a script that I’m going to shoot, there are a number of things I’m looking out for. I want to identify the themes and the character arcs, so that I can come up with ways of reflecting these in the cinematography (see my previous blog post for examples). And on a more mundane practical level, I’m figuring out what equipment is required, and which scenes or sequences might be difficult photographically.

To demonstrate my thought process in planning a project, I thought I would share with you today the things I highlighted in a particular script and why. The script in question is The Gong Fu Connection, written by Ted Duran, and we start shooting it this Friday. It’s an action-comedy drama in which a young Chinese businessman learns a life lesson via his connection with an Englishman who has introduced Kung Fu in a farm community in Sussex. You can help us make the film by going to www.indiegogo.com/projects/the-gong-fu-connection and contributing, or by spreading the word on your social media networks.

Throughout the script I’ve highlighted the time of day in the slug lines. One of the first things I need to know as a DP is, “Are there are night scenes?” because that will have a big effect on the lighting equipment needed. Ted’s script is nice and specific, not just DAY or NIGHT, but DAWN, MORNING, AFTERNOON, EVENING and DUSK. This is a really helpful starting point in considering the light. In general I see that there are a lot of daylight exteriors, so bounce and negative fill are going to be my two chief weapons.

The very first slug line is:

1. INT. VICTORIA STATION – MORNING

Immediately I’m wondering, “Is this going to be a guerilla shoot or are we going to have permission?” Clearly we will never be allowed large lighting set-ups and we will always be working around the general public. Battery-powered LED panels will come in handy here.

A little lower down the page is:

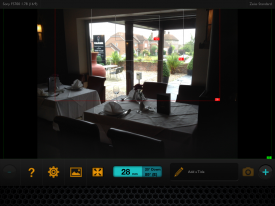

3. INT. RESTAURANT – DAY

Straight away I’m thinking, “Should it be night instead?” Even though in summer you may go to a restaurant in daylight, somehow it feels like it wouldn’t look right on camera. I make a note to discuss this with Ted on the recce, and indeed we end up deciding to shoot it after dark.

The next scene features a phone conversation. I make a note to ask if the person on the other end of the line will be seen.

Another station scene contains the direction:

He gets on the train… The train whizzes past an urban landscape…

I highlight this, to remind myself that this is a hidden extra scene – on board the train, as opposed to at the station. Again I’m wondering what the extent of permissions will be and what restrictions there may be on equipment. I also highlight other hidden extra scenes later on – an interior bedroom scene in which a character sees another character outside through the window, and a montage set in a variety of different places and times.

I highlight the following in a café scene:

Time passes, we see the clock tick past… Half an hour and two coffees later…

Maybe there are jump cuts here to show the passing of time? I’ll want to adjust the keylight outside the window to simulate the progress of the sun.

A violent flashback takes place in an apartment. Although the script specifies DAY, the content makes me imagine the look a little differently. I write the following notes: “Dingy look? TV light? Maybe night. Rough, handheld fight. No finesse or control.” Ultimately Ted and I do decide to set the scene at night. The flickering TV set will be a key light source. The handheld look will contrast with the more slick steadicam and tripod work which will characterise the Kung Fu fights later on in the film.

A more pastoral scene features two characters walking and talking beside a lake. I write: “Watery reflections? Bounce M18 off surface of water?” I’m thinking to enhance the beauty of the setting by using the rippling water surface to bounce an ArriMax M18 onto the characters’ faces.

A direction later on reads, “He is lost in his own world.” I write “push in?” beside this as a shot suggestion. Then I read:

Startled, he turns around to see a man towering over him in his dressing gown with a long plaited beard, who looks at him with a frown on his face.

This character, Mandragor, clearly has a special signficance, a mystical presence. I write “special lighting for Mandragor?” next to this passage. This will probably be stronger backlight or perhaps an unusual eyelight of some kind. I highlight his other appearances in the film too.

A dawn scene specifies that “the sun has just risen”, which I highlight. If it’s a cloudy day, or we’re unable to shoot at dawn, I may need to fake this with an orange-gelled HMI.

Later on, a direction reads:

RICKY smiles, then looks at AERONA dreamily.

I highlight this and write “classic beauty shot” above. I won’t go as far as a soft-focus filter, but the lighting needs to be particularly flattering here to represent Ricky’s enamoured POV.

A flashback in a pub has a nice clear description which is a great springboard for the cinematography:

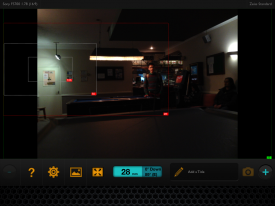

… Playing pool in a dark room in a grungy pub…

I’m immediately thinking smoke, shadows, pools of light from the over-table fixtures. I also highlight the word “laptop” since the screen will be a light source which I may want to use or beef up with a hidden LED panel perhaps.

Later on I’ve highlighted a dialogue scene in a moving car. I need to talk to Ted about how he wants to shoot it, and to think about how the camera can be rigged to get those shots.

The only time a specific shot is mentioned in the script is here:

Ricky is running as fast as he can. We see a close up on his face as he thinks.

I highlight this, knowing that it will be tricky to accomplish and hoping that Colin Smith, our steadicam operator, will be up to the challenge!

Having read the script a couple of times, I go back and make some notes on the cover page about the general photographic approach:

City – dark, dingy, oppressive, handheld, little/no eyelight – handheld?

Country – light, backlit, bounce-from-below

Characters with no connection – Lucia, the bad guys, Ricky to begin with – are framed in clean singles. Handheld or stiff tripod.

Characters with connection – Matthew, his posse, Ricky as the film goes on – are framed in 2- shots and dirty singles. There are more fluid shots with pans or tracks.

And that’s all. Some of these notes are just for me to think about, while others raised questions I needed to ask the director and producer about. Preparation is key in filmmaking, and in the heat and stress of the shoot I’ll be glad I gave some consideration to these issues in advance.