Painting with Light is a book I first heard about when Hollywood DP Shane Hurlbut recommended it on his excellent blog. Browsing the shop at the BFI Southbank recently I came across a copy, liked what I saw… and went home and ordered it on line. Them’s the breaks.

Painting with Light is a book I first heard about when Hollywood DP Shane Hurlbut recommended it on his excellent blog. Browsing the shop at the BFI Southbank recently I came across a copy, liked what I saw… and went home and ordered it on line. Them’s the breaks.

John Alton was something of a rebel. In an era when most DPs used complex lighting set-ups hung from the studio grid, Alton lit from the floor, using fewer sources, and was consequently faster. This made him unpopular with his peers. A strained, in-out relationship with the American Society of Cinematographers didn’t help. He sometimes clashed with other heads of department too, notably designers, who didn’t like the way his lighting made their work look. But directors and producers loved him because he worked quickly.

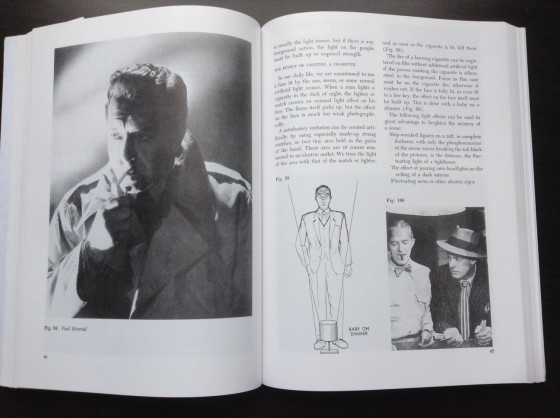

When Painting with Light was published in 1949, Alton was emerging as a key cinematographer of the film noir genre. Today he is remembered as one of the masters of noir. His utterly black shadows, backlit fog and slatted keylights defined the visuals of films like The T-Men (1947, dur. Anthony Mann) and The Big Combo (1955, dir. Joseph H. Lewis).

However, noir lighting – or “Mystery Lighting” as Alton terms it – occupies only one chapter of Painting with Light. Two preceding chapters cover the basics of Hollywood filmmaking and introduce lighting equipment, most of which is now obsolete. Subsequent chapters cover “Special Illumination” – predominantly weather effects and vehicle interiors, “The Hollywood Close-up” – looking at key angles and introducing a clock system not dissimilar to the one I once blogged about – and “Outdoor Photography”.

The book then diverges from filmmaking, offering advice to novice photographers taking holiday snaps or equipping a portrait studio. Chapter nine, “Visual Music”, explores lighting and composition in terms of a musical allegory, each shot contributing to the symphony of the movie. Chapter twelve is the strangest, urging women to be aware of how their faces are lit as they go about their lives so that they can ensure they are always seen to their best advantage. All cinematographers know that beauty is as much about lighting as it is about bone structure and make-up, but I can’t see that idea ever catching on outside of the industry. Brief chapters on film processing, suggested improvements to cinemas, and the human eye as a camera, round out this mixed bag. A foreword, a lengthy but interesting biography and a filmography introduce the current edition.

While many of the ideas and principles put forward by Alton are still relevant today, some of it serves more as a historical record of cinematography in the mid-twentieth century. Curiously propounding the system he apparently rebelled against (I wonder how different the book might have been had he written it at the end of his noir period), Alton paints a picture of a time in which cinematography was much more complex and artificial. Whereas today we talk of the three-point lighting system of key, fill and backlight, Alton speaks of an eight light system, adding:

- eyelight – to give a sparkle in the eye

- kicker – a three-quarter backlight to define the jaw

- clotheslight – a cross-light to bring out the texture of the costumes

- filler – not to be confused with fill, the filler is purely to cure vertical shadows from a high keylight

- background light

While the modern cinematographer is aware of all of the above and tries to incorporate them, he or she tries to make lamps pull double- or triple-duty and would almost never use eight lamps to light a single close-up. Alton also advocates abandoning all of your wide-shot lighting and starting again from scratch for the close-up, to beautify your star; today’s audiences would not accept the mis-match of such radically re-lit close-ups. He talks of flag and grip equipment which could never work with today’s dynamic blocking and camera movement, like a “chin scrim” designed to cast a very specific shadow on the collar of a white dinner jacket to stop it blowing out.

But some sections still have undeniable value today. Alton looks at different types of faces and how to light each to their best advantage, how to light a dinner table or a campfire scene, and how to light for different times of day. He maintains that movie lighting should always mimic what natural light does in real life – hard to believe, but this was quite a radical concept in 1949. Examples and diagrams are used throughout to illustrate his techniques.

For me the most interesting part was his insight into depth in cinematography. Many DPs, myself included, feel that a shot looks best when the foreground is dark, the midground is correctly exposed and the background is bright. Alton offers the following explanation of this phenomenon:

At night when we look into an illuminated room from the dark outside, we can see inside but cannot be seen ourselves. A similar situation exists in the motion picture theatre during a performance. We sit in the dark looking at a light screen; this gives a definite feeling of depth. In order to continue this depth on the screen, the progression from dark to light must be followed up. The spot which should appear to be the most distant should be the lightest, and vice versa…

I have no doubt that there are more useful tomes on the market for a student of contemporary cinematography, but if you like a bit of history along with useful tips you’ll find Painting with Light a good read. Like a time capsule, reading Alton’s book today reveals which bits of the past were transient fads and which were timeless universal truths. The importance of depth, the tricks of lighting for different faces, the textural power of cross-lighting, the drama of back-lighting… There are plenty of timeless truths here, and in learning them from Alton you’ll be following in the footsteps of many great cinematographers.