If Roger Deakins is the greatest living cinematographer, Jack Cardiff must be the greatest one no longer with us. He is perhaps best known for his triptych of Technicolor collaborations with Powell & Pressburger – A Matter of Life and Death, Black Narcissus (which won Cardiff an Oscar and a Golden Globe) and The Red Shoes. But his career spanned a huge swathe of cinematic history, beginning in the days of the silent film and concluding in the age of action blockbusters like Rambo: First Blood Part II. Along the way he photographed many of the twentieth century’s most iconic movie stars: Humphrey Bogart, Sophia Loren, Errol Flynn, Marilyn Monroe, Laurence Olivier, Audrey Hepburn and Kirk Douglas, to name but a few.

If Roger Deakins is the greatest living cinematographer, Jack Cardiff must be the greatest one no longer with us. He is perhaps best known for his triptych of Technicolor collaborations with Powell & Pressburger – A Matter of Life and Death, Black Narcissus (which won Cardiff an Oscar and a Golden Globe) and The Red Shoes. But his career spanned a huge swathe of cinematic history, beginning in the days of the silent film and concluding in the age of action blockbusters like Rambo: First Blood Part II. Along the way he photographed many of the twentieth century’s most iconic movie stars: Humphrey Bogart, Sophia Loren, Errol Flynn, Marilyn Monroe, Laurence Olivier, Audrey Hepburn and Kirk Douglas, to name but a few.

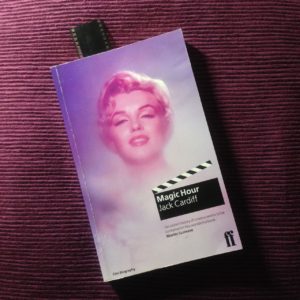

Magic Hour is Cardiff’s autobiography, first published in 1996. (Yes, I’m reviewing this book 21 years late. Sorry.) From the beginning, his life was remarkable. His parents were travelling music hall performers, and he never stayed at the same school for long. But what he might have lacked in conventional education he more than made up for with a voracious appetite for literature and fine art.

One day, gazing at a roomful of paintings, I realized something starkly obvious that I’d never noticed before. Light! Now I gave all my attention to the way painters used light and also began the habit of analysing the light all around me: in rooms, buses, trains – everywhere. How light plays subtle tricks, bouncing off walls, how its various reflections and changed light sources can reveal much insight into the character of a face.

After a few movie appearances as a child actor, Cardiff found work as a camera assistant at Elstree, eventually rising to the rank of camera operator. One day, he and his fellow operators were interviewed to see who would go to America to learn all about the new Technicolor process. Cardiff cut short the technical questions and held forth on the great painters who inspired him. He was selected.

The Technicolor camera was enormous and required precision maintenance, but Cardiff was to get stunning results from it.

Over the next quarter of a century, until the advent of single-film Eastmancolor, which tolled the death knell of the three-strip camera, I used this superb Rolls-Royce of a beauty all over the world in all kinds of dangerous situations: in steel foundries (inches away from molten ingots), in battleships in wartime seas, on top of erupting volcanoes, in burning deserts and steaming jungles, and diving on to the Colosseum in Rome in an old Italian bomber.

The above passage neatly sums up the kind of adventures Cardiff chronicles in Magic Hour. Anyone who’s ever worked on a film set will have a few ridiculous anecdotes to tell, and this man had a lifetime’s worth. For example, during World War II, Cardiff was tapped to lens a propaganda drama called Western Approaches. One scene required the sinking of a submarine, which was achieved without VFX of any kind, with the vessel doing a controlled dive to end up just short of total submersion. “My Technicolor camera was tied on to the extreme tip of the stern,” wrote Cardiff, “and I was operating it!”

After the war he came to the attention of director/producer team Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger, leading to that famous triptych noted in my introduction, before going on to work with many other renowned filmmakers. His collaboration with Hitchcock, Under Capricorn, featured a memorable scene in which the four-foot-high Technicolor camera was required to track along the length of a dining table. This being impossible, the table was rigged to split apart as the camera advanced.

Now the camera moved forward, seemingly on an inevitable collision course, but at the last moment, each of the guests fell back on to a mattress clutching his section of the table with all the props stuck on it!

Magic Hour is beautifully and sincerely written, making you wish you could share a pint with the great man and hear even more of his beguiling tales of cinematic capers. Throughout the book, he provides unique insights into the off-screen lives of the Hollywood icons he worked alongside: his friendship with the “childlike, frightened Marilyn”; his unconsummated romance with Sophia Loren; his chat with Errol Flynn about the latter’s womanising, and many others.

We are also treated to fascinating glimpses into Cardiff’s creativity as a cinematographer. For example, when faced with an exterior close-up whose grey, cloudy background would not match earlier sunny wide shots, Cardiff shone an ungelled tungsten lamp on the talent and instructed the lab to correct for his skin tone. The lab duly added blue to the print, restoring the talent’s skin tone to normal and tinting the grey sky a perfect blue! Can you imagine performing such a risky experiment and not knowing until the following day whether it had succeeded or not? We digital DPs are truly spoilt.

Another example of Cardiff’s ingenuity was on 1956’s War and Peace, where he had to create a sunrise effect on a glass matte painting.

I placed a small lamp close beside my camera which was brightly reflected in the sheet of glass. [This had] pink and orange filters on it. Although a tiny lamp, its reflection in the glass looked exactly like a dawn sun on the horizon.

In the late fifities, Cardiff moved into directing, and the great critical and commercial success of his 1960 film Sons and Lovers forms the denouement of Magic Hour. He later returned to DPing with such mainstream movies as Death on the Nile and Conan the Destroyer, a period of his life which Cardiff gives only a passing mention in the closing chapter. Perhaps he was less proud of the modern box office fodder than his earlier, arguably more artistic, work?

Cardiff died in 2009, the year before the release of the documentary feature Cameraman: The Life and Word of Jack Cardiff. Whether you choose to learn about Cardiff’s contributions to cinema from that excellent film or from the equally absorbing Magic Hour, learn you should. The word “legendary” is over-used, but Cardiff is more deserving of the adjective than most.