What angle the key light hits a character at is a KEY (groan) decision for a director of photography. The lighting featurette in my last post looked at some of the options, but today I’d like to expand on those with some more up-to-date examples.

Imagine a clock face. You’re looking down on the scene and your talent is at the centre with their eyeline to twelve o’clock.

With that in mind, consider the following shots. The camera is at between twelve and one o’clock in each case.

Clearly the level of fill makes a big difference, but you can already see that a key light at noon gives a flawless, evenly lit look which is great for a leading lady, while a half-past-nine casts half of the face into darkness for a threatening or mysterious feel. There is a sweet spot I love at about quarter to eleven where, on one side of the face, only the eye and a triangle on the cheek are lit. But generally between half past ten and half past eleven models the face nicely.

In all of the above examples, with the camera at one-ish, the key was between nine and twelve, i.e. the key was on the opposite side of the eyeline to the camera. This is known as lighting the “downside” – the side away from camera. Most cinematographers, myself included, consider this the most pleasing side to light from, as it shows the shape of the face and gives a nice shadow area on the camera side into which you can dial your preferred amount of fill.

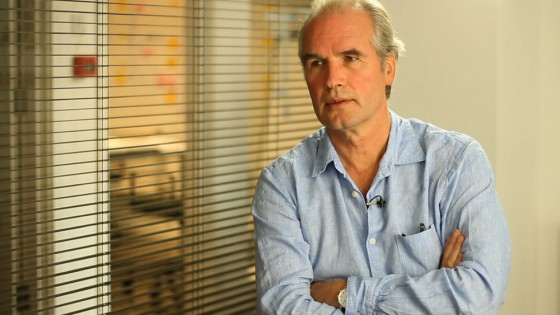

Here is an example of lighting the upside:

In many scenes, the position of the keylight will be dictated by the layout of the set or location, so a DP should consider this in pre-production discussions with the production designer, on location scouts or when the director is blocking the actors.