Award-winning visual effects artist Douglas Trumbull died recently, leaving behind a body of memorable work including the slit-scan “Stargate” sequence from 2001: A Space Odyssey. But what is slit-scan and where else has it been used?

Award-winning visual effects artist Douglas Trumbull died recently, leaving behind a body of memorable work including the slit-scan “Stargate” sequence from 2001: A Space Odyssey. But what is slit-scan and where else has it been used?

Slit-scan has its origins in still photography of the 1800s. A mask with a slit in it would be placed in front of the photographic plate, and the slit would be moved during the exposure. It was like a deliberate version of the rolling shutter effect of a digital sensor, where different lines of the image are offset slightly in time.

The technique could be used to capture a panorama onto a curved plate by having the lens (with a slit behind it) rotate in the centre of the curve. Later it was adapted into strip photography, a method used to capture photo-finishes at horse races. This time the slit would be stationary and the film would move behind it. The result would be an image in which the horizontal axis represented not a spatial dimension but a temporal one.

Such a collision of time and space was exactly what Stanley Kubrick required for the Stargate sequence in 2001: A Space Odyssey, when astronaut Dr David Bowman is treated to a mind-warping journey by the alien monolith.

Douglas Trumbull, then only 25, had already been working on the film for a couple of years, first producing graphics for the monitors in the spacecraft (all done with physical photography), then detailing and shooting miniatures like the moon bus, creating planets by projecting painted slides onto plexiglass hemispheres, and so on, eventually earning a “special photographic effects supervisor” credit.

“The story called for something that represented this transit into another dimension,” Trumbull said of the Stargate in a 2011 interview with ABC, “something that would be completely abstract, not something you could aim a camera at in the real world.

“I had been exposed to some things like time-lapse photography and what is called ‘streak photography’,” he continued, referring to long exposures which turn a point light source into a streak on film.

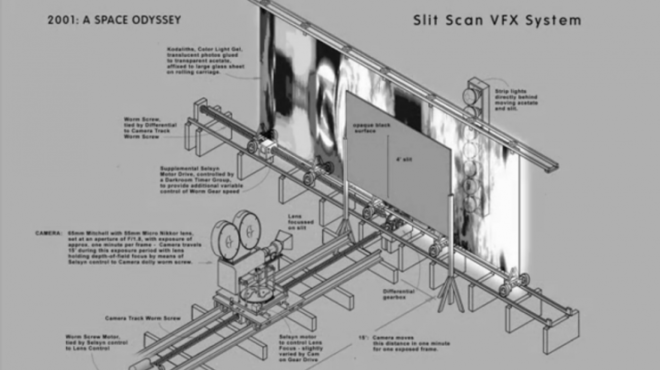

This germ of an idea developed into a large and elaborate machine that took five minutes to shoot a single frame.

The camera was mounted on a special tracking dolly driven by a worm gear to ensure slow, precise movement. While exposing a single frame it would creep towards a large black mask with a 4ft-high slit in it. Behind the slit was a piece of backlit artwork mounted on a carriage that could move perpendicularly to the camera. This artwork – an abstract painting or a photo blow-up of flowers or coral – slid slowly to the right or left as the camera tracked towards it. Remember, this was all just to capture one frame.

The resulting image showed a wall of patterned light stretching into the distance – a wall generated by that slit streaking across the frame.

For each new frame of film the process was repeated with the artwork starting in a slightly different position. Then the whole strip of film was exposed a second time with the camera adjusted so that the slit now produced a second wall on the other side of frame, creating a tunnel.

The Stargate sequence was unlike anything audiences had seen before, and one of the many people inspired by it was the BBC’s Bernard Lodge, who was responsible for creating Doctor Who’s title sequences at the time. For early versions he had used a ‘howl-around’ technique, pointing a camera at a monitor showing its own output, but when a new look was requested in 1973 he decided to employ slit-scan.

Lodge used circles, diamonds and even the silhouette of Jon Pertwee’s Doctor rather than a straight slit, creating tunnels of corresponding shapes. Instead of artwork he used stressed polythene bags shot through polarising filters to create abstract textures. The sequence was updated to incorporate Tom Baker when he took over the lead role the following year, and lasted until the end of the decade.

An adaptation of slit-scan was used in another sci-fi classic, Star Trek: The Next Generation, where it was used to show the Enterprise-D elongating as it goes to warp. This time a slit of light was projected onto the miniature ship, scanning across it as the camera pulled back and a single frame was exposed. “It appears to stretch, like a rubber band expanding and then catching back up to itself,” visual effects supervisor Robert Legato told American Cinematographer. “This process can only be used for a couple of shots, though; it’s very expensive.”

Thanks to CGI, such shots are now quick, cheap and easy, but the iconic images produced by the painstaking analogue techniques of artists like Douglas Trumbull will live on for many years to come.