Yesterday I paid a visit to my friend Chris Bouchard, co-director of The Little Mermaid and director of the hugely popular Lord of the Rings fan film The Hunt for Gollum. Chris has been spending a lot of time working with Unreal, the gaming engine, to shape it into a filmmaking tool.

The use of Unreal Engine in LED volumes has been getting a lot of press lately. The Mandalorian famously uses this virtual production technology, filming actors against live-rendered CG backgrounds displayed on large LED walls. What Chris is working on is a little bit different. He’s taking footage shot against a conventional green screen and using Unreal to create background environments and camera movements in post-production. He’s also playing with Unreal’s MetaHumans, realistic virtual models of people. The faces of these MetaHumans can be puppeteered in real time by face-capturing an actor through a phone or webcam.

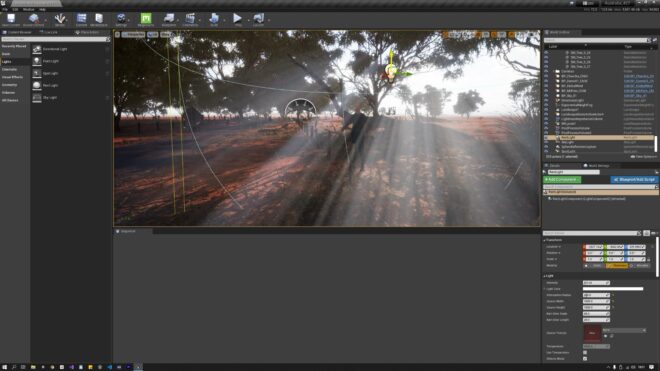

Chris showed me some of the environments and MetaHumans he has been working on, adapted from pre-built library models. While our friend Ash drove the facial expressions of the MetaHuman, I could use the mouse and keyboard to move around and find shots, changing the focal length and aperture at will. (Aperture and exposure were not connected in this virtual environment – changing the f-stop only altered the depth of field – but I’m told these are easy enough to link if desired.) I also had complete control of the lighting. This meant that I could re-position the sun with a click and drag, turn God rays on and off, add haze, adjust the level of ambient sky-light, and so on.

Of course, I tended to position the sun as backlight. Adding a virtual bounce board would have been too taxing for the computer, so instead I created a “Rect Light”, a soft rectangular light source of any width and height I desired. With one of these I could get a similar look to a 12×12′ Ultrabounce.

The system is pretty intuitive and it wasn’t hard at all to pick up the basics. There are, however, a lot of settings. To be a user-friendly tool, many of these settings would need to be stripped out and perhaps others like aperture and exposure should be linked together. Simple things like renaming a “Rect Light” to a soft light would help too.

The system raises an interesting creative question. Do you make the image look like real life, or like a movie, or as perfect as possible? We DPs might like to think our physically filmed images are realistic, but that’s not always the case; a cinematic night exterior bears little resemblance to genuinely being outdoors at night, for example. It is interesting that games designers, like the one below (who actually uses a couple of images from my blog as references around 3:58), are far more interested in replicating the artificial lighting of movies than going for something more naturalistic.

As physical cinematographers we are also restricted by the limitations of time, equipment and the laws of physics. Freed from these shackles, we could create “perfect” images, but is that really a good idea? The Hobbit‘s endless sunset and sunrise scenes show how tedious and unbelievable “perfection” can get.

There is no denying that the technology is incredibly impressive, and constantly improving. Ash had brought along his Playstation 5 and we watched The Matrix Awakens, a semi-interactive film using real-time rendering. Genuine footage of Keanu Reeves and Carrie-Anne Moss is intercut with MetaHumans and an incredibly detailed city which you can explore. If you dig into the menu you can also adjust some camera settings and take photos. I’ll leave you with a few that I captured as I roamed the streets of this cyber-metropolis.