Directing A Cautionary Tale last week was a very satisfying experience. There are a number of reasons for this – one is that, unlike when Stop/Eject wrapped, we are not now faced with the task of creating visual effects, shooting pick-ups and doing ADR. I’m pretty sure we got everything we needed in the can in that whirlwind three day shoot.

But the main reason is that it’s been one of the most collaborative directing experiences of my career. I’ve written before about the process of surrendering filmmaking roles to collaborators, and the joy of receiving contributions from those collaborators which far outstrip what you could have done yourself. With A Cautionary Tale I’ve finally reached a point where I am directing and ONLY directing. (We will gloss over the bit of focus-pulling I had to do on a few shots.)

It was great to leave the job of lighting and photographing the film completely to Alex Nevill, who did a beautiful job, and it’s nice to sit back and wait for editor Tristan Ofield’s first cut. It was also really, really good not to have to worry about the logistical side of things.

But the biggest relevation and the biggest benefit was in the improved relationship I was able to have with the actors. Freed from the invisible cord which tethers a DP to their camera, and without the concerns of a producer littering my mind, I was able (I hope) to give the cast far more attention. It is not often in my career that I have been able to sit in a trailer (okay… it was a caravan) and discuss the upcoming scene with the actors, but I got to do it on A Cautionary Tale.

Despite the late casting of Frank Simms as Gordon, I had been able to meet both Frank and lead actress Georgia Winters prior to the shoot and do some good groundwork on their characters. Here too I found the process more collaborative than I have done in the past, for the simple reason that I had not written the script. A writer-director is very close to his or her story and tends to have a very strong idea of how everything should be played. A non-hyphenate director, however, has no greater insight into the script than the actors. The result is that I found I was usually asking the actors questions, to invite discussion, rather than issuing them with instructions. I suppose some might see this as a lack of vision on my part, but I’m pretty sure it will lead to a richer end product.

Throughout the shoot I tried to maintain my philosophy of keeping the number of takes to a minimum, as discussed in a 2011 blog entry. At points it made me unpopular with Alex, but long and bitter experience has taught me that it is not worth doing another take just because of minor camera wobbles. Yes, your operator might get the camerawork perfect on the next take, but something else will go wrong – a loud motorbike going by, for example – and before you know it, it’s twenty minutes later, you’ve done four more takes to get everything technically perfect, and now the performances are no longer fresh, so you use take one in the edit anyway! Don’t go chasing the take where everything’s perfect, because it will never happen. Just make sure the performance is perfect and the audience will forgive everything else – hell, they probably won’t even notice that camera wobble once it’s cut smoothly with the surrounding shots and the sound is nicely mixed.

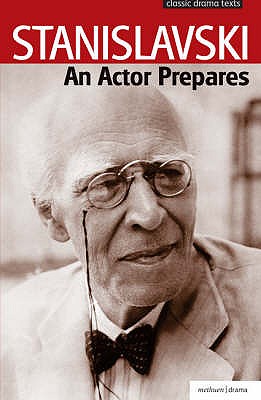

Reading Stanislavski definitely paid off. He underlined the importance of a fresh performance built on unique creative inspiration, chiming in with my point above. And I was even able to use a “magic if” when directing the closing shot of the film. I strongly recommend reading An Actor Prepares if you want to better understand how to engage with actors.

Stay tuned for more on A Cautionary Tale as we progress through post.