Last summer I lensed Harvey Greenfield is Running Late, a hilarious comedy feature starring Paul Richards, based on his acclaimed one-man play, soon to have its 100th performance. We had a 14-day window in Paul’s schedule for the shoot, during which we captured two thirds of the film – less than we’d hoped, but still a remarkable achievement given the resources we had and the production value we achieved. This summer we shoot the rest.

Day 15

Ten months on, we returned to the house from days 11 and 12. It’s on the verge of being sold, and this was our last chance to mop up the outstanding material here.

Ten months on, we returned to the house from days 11 and 12. It’s on the verge of being sold, and this was our last chance to mop up the outstanding material here.

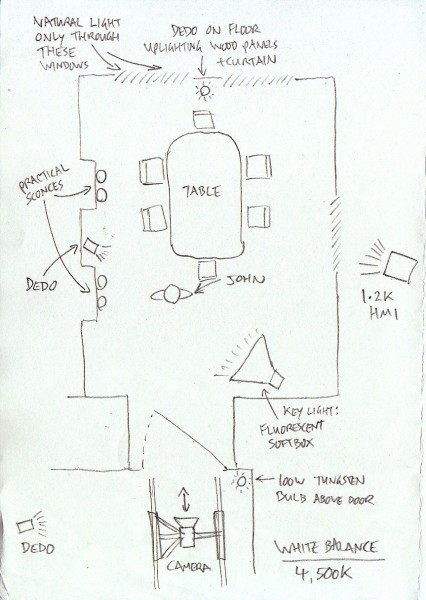

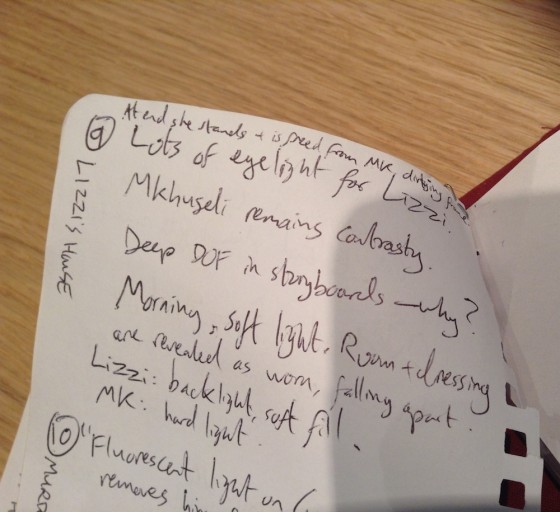

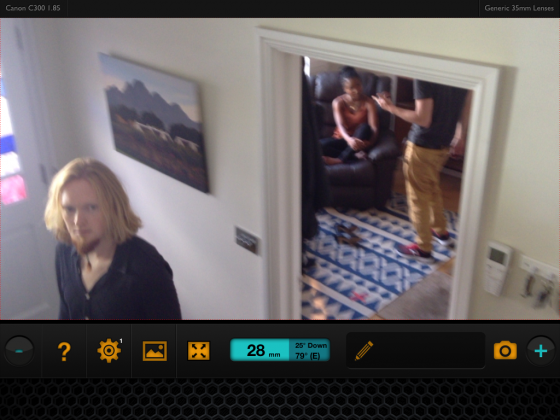

We eased into it gradually with simple inserts, recreating the look and lighting in the kitchen using Fifi’s camera notes, clips from the assembly edit, and this blog (yes, it’s not just for you, dear reader). At times like this I wish I recorded even more information – intensity and colour temperature readings for every source would be extremely useful, but is that really practical?

After traumatising Paul with a reshoot of a scene in which he gets slapped (accidentally for real the first time around) we popped outside to get a shot of him on the street, filmed through a car windscreen. Last year we captured the first monologue of the film as a oner, but with hindsight director Jonnie Howard decided it needed breaking up; this windscreen shot is one of several that he has added to illustrate the things Harvey monologues about. Proving that there are no easy shots, it took me an embarrassingly long time to eliminate annoying reflections in the glass by covering shiny parts of the dashboard with matt black tape and putting a polarising filter in the matte box.

Next we moved to the back garden for one of the film’s most complicated shots. It starts off as a two-shot of Harvey and Alice (Liz Barker) in a nighttime interior setting then – via a low-tech, Michel Gondry-style transition – becomes a single of Harvey in a daytime exterior. Gaffer Stephen Allwright and spark Jeremy Dawson built a dark box out of flags and bolton, parts of which had to swing away to let in the natural light during the transition. A light had to be panned off and a reflector swung in too, while production designer Amanda Stekly and her helpers performed their own magic with the set. By the time we got it in the can we were losing the light, but the result was well worth it.

The dusk gave us just the look we needed for a quick scene in the bedroom, then we were into full nighttime scenes. I climbed into the wardrobe to get the right camera angle – we were without our beloved 14mm lens this time around, so the locations felt a little tighter!

Later we had to recreate the lighting of the aforementioned oner, so we could shoot coverage, again with extensive reference to the camera notes, rushes and R3D metadata, this blog, and on-set photos captured on my phone. Last year we dialled a custom cyan colour into the Astera tubes and I really wish I had noted the XY or HSL numbers so that we could have dialled those into the Rayzr MC 200 that was replacing them for the pick-ups. Instead we had to judge it by eye.

It was now about midnight and we still had an important sequence in the kitchen and living room to shoot; we ultimately captured it in two set-ups and an insert. This day’s filming had seen the most extreme examples of the colour scheme I planned last year: orangey-red colours to represent Harvey’s stress, and cooler, greenish shades for calmer moments. By the end of the night it was starting to look like The Neon Demon and I was wondering if I had gone too far. I guess I will find out when it’s all cut together.

Day 16

A pleasant cycle ride through Cambridge and out across a meadow brought me to the brand-new village of Eddington and the impressive Storey’s Field Centre where we would be filming the office of Harvey’s boss, Bryan (Alan Hay). First up was a fantastic shot of Harvey huffing and puffing up a spiral staircase in the centre’s main hall. The high-tech building had its lights and two layers of blinds controlled electronically, and Stephen was able to completely reshape the natural light in the huge wide shot and even put a glorious streak of light on the staircase just by pressing a few buttons. If only every location was equipped so.

A smaller, but still obscenely spacious, hall served as Bryan’s office. French windows faced east into a beautiful courtyard garden. High windows on the opposite side of the room featured motorised blinds again, which sadly would not stop halfway, forcing us to close them completely to control the light. An overhang above the French windows, combined with the high walls of the courtyard, meant that very little natural light now entered the room. For a key, Stephen constructed a book-light by pointing an Aputure 600D up into a tilted frame of Ultrabounce and then hanging some diffusion (half grid, I think) off the top edge. We added a tungsten fresnel on a boom to give some orange, stress-themed hair-light to characters in the middle of the room.

The first shot was effectively the POV of a dartboard, so we stuck three darts to the matte box with Blu Tack. Sharp points and oily substances – exactly the things you want right next to your lens! – but it looked great.

The next couple of shots featured co-writer Raymond Howard’s baby daughter. One was a contra-zoom, captured on the 18-35mm which I zoomed manually off the barrel while pushing in on the Tango ProSup slider. The other required me to brandish the handheld camera right in baby’s face for a very long time until she eventually cried.

Then it was onto the big scene. This featured Bryan referring to a PowerPoint presentation, which meant a lighting transition as the screen came down and the projector fired up. For Harvey’s angle, with his back to the projector, we boomed an Aputure 300D behind him to simulate the projection beam, and sat a pocket LED light on the matte box to represent the bounce off the screen; these faded up as the 600D book-light and tungsten hair-light dimmed down. For Bryan’s angle the real projection light wasn’t doing enough on his face, so we “extended” the practical lamp on his desk with a small tungsten fresnel. For the wide shot we could get away with re-angling the practical so that it cast a dramatic, Citizen Kane-esque shadow from Bryan up onto the screen.

All in all, the day’s work added a huge amount of scale and humour to the movie. It was lovely to see and work with everyone again for the weekend. Next month most of us will be back for eight more days of running late.

12:46am We carry on with the scene, getting some very cool shots in the can, before wrapping a little after midnight. The kit is packed away in the living room, ready to load into the van tomorrow. Cider and sleep beckon.

12:46am We carry on with the scene, getting some very cool shots in the can, before wrapping a little after midnight. The kit is packed away in the living room, ready to load into the van tomorrow. Cider and sleep beckon.