Following my personal observations on the shot planning process the other day, here’s a look at that process in action and a record of some of the thoughts that go through my head as a director when I’m choosing camera angles.

Everything begins with the script, and here is the extract for the Stop/Eject sequence I’m going to break down:

14. INT. ALCOVE/EXT. RIVER GARDENS – DAY – INTERCUTKATE stands behind the alcove’s curtain with an armful of tapes. She pushes one into the recorder – “JULY 16th 2007, 5-6:30pm” - and hits PLAY. Warm summer sunshine steals in through the crack in the curtain. She pulls it back to reveal the river, sunlight dancing and sparkling in the water of the weir.COPY-KATE cycles through the gardens on a creaky old bicycle with a custom paint job and various doodads hanging off, oblivious to her other self and the alcove stood in the middle of a Victorian bandstand.Copy-Kate spots a strange figure on the riverbank, wearing closed-back headphones and waving a big, fluffy microphone at the running water. She looks ahead – she’s about to run over TWO YOUNG GIRLS. She grips the brakes tightly and the bike screeches to a stop with a noise like a small army of warring cats. She catches her breath as the older girl scowls and drags her sister away.

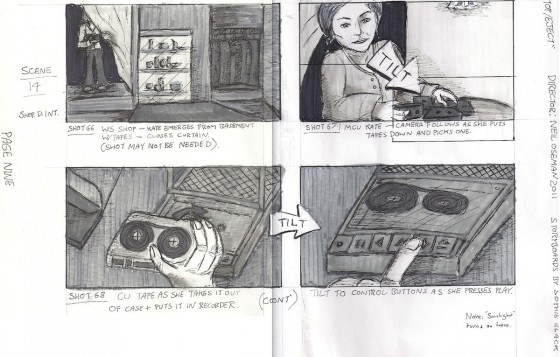

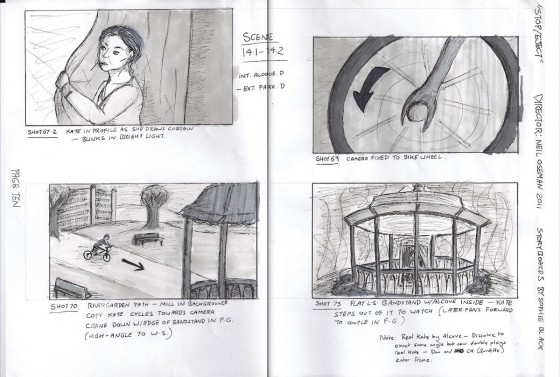

Sophie drew the following storyboards for this sequence, based on my rough sketches:

I don’t like starting scenes with establishing shots; I prefer to reveal them gradually. So when I conceived the first shot (top left) – setting up Kate in the alcove in the shop – I suspected I would probably end up cutting it, and sure enough I never even filmed it. The audience would know by now where the tape recorder alcove was, I figured.

The next shot (top right) follows Kate as she puts down the stack of tapes. This is fairly basic visual storytelling. The audience already knows that the tapes contain recordings of Kate’s life. When we see her come in with an armful of cassettes, we anticipate her nostalgia trip.

As this was the first time Kate was to travel back in time more than a few hours, I felt it important to show the action of the tape going into the recorder in close-up (bottom), to ensure the audience understood the connection between the tapes, the machine and the time travelling.

We then return (top left) to the previous angle, following Kate as she stands back up and opens the curtain. One of my regrets with Stop/Eject was that I never shot over Kate’s shoulder as she looked out of the alcove. I can only think this is because I was trying to avoid doing “the obvious thing”. In this scene I chose instead to tease what she’s seeing, revealing first the sunlight on her face, and then (top right) an abstract close-up of a spinning bike wheel, part of the visual theme of circles I had smart-arsedly developed for the film. My thinking was that time travel was a big and unbelievable concept for Kate to take in, so it needed to be broken to her (and therefore us) gradually.

Finally the scene is revealed (bottom left) in a high wide shot to establish the geography, which then cranes down to draw us into the action. On the day, there was a bush in the foreground, which began to obscure the action as we craned down, so we decided to crane up instead, rising up over the bush to reveal the action.

Next it was necessary to show the place of Kate and the alcove in the geography. I wanted to echo the formality and symmetry of the bandstand’s architecture by framing it flat-on, dead centre (bottom right).

Then Copy-Kate sees Dan, her future husband, for the very first time. I wanted to show an immediate connection using an over-the-shoulder shot-reverse. Since Copy-Kate was on a moving bike, this meant panning with her for her angle (top) and then tracking with her for Dan’s angle (bottom) in order to keep her shoulder in frame. I left Dan’s shoulder out of Kate’s shot since he hasn’t seen her yet and so hasn’t made a connection.

Then Copy-Kate sees Dan, her future husband, for the very first time. I wanted to show an immediate connection using an over-the-shoulder shot-reverse. Since Copy-Kate was on a moving bike, this meant panning with her for her angle (top) and then tracking with her for Dan’s angle (bottom) in order to keep her shoulder in frame. I left Dan’s shoulder out of Kate’s shot since he hasn’t seen her yet and so hasn’t made a connection.

The editing podcast below from summer 2012 explains the various iterations I went through with this sequence. (I later brought Miguel Ferros on board to re-edit the film, and his final version is far superior to all of my attempts.) You can see in the podcast some of the problems that my linear shot planning approach caused, notably my failure to cover the whole scene in the crane shot, and the restrictions which that placed on me in the edit.

Despite these minor quibbles, I’m very proud of Stop/Eject and its visual storytelling. It’s recently received a couple of glowing reviews on Unsung Films and The London Film Review, the latter praising its visuals, and both quite rightly lauding Georgina Sherrington’s brilliant lead performance.