A couple of weeks ago I shared my thoughts about whether a director of photography should own equipment. My conclusion was that it can be useful early in your career, when you’re shooting corporates or tiny films with no hire budget. So what is the best camera for indie cinematography?

I’m not going to answer that, but I will tell you what to look for when investing in a camera. Hopefully these tips will help you choose the one that’s right for you from the huge and ever-changing array of professional cameras on the market, from the humble DSLR to the ubiquitous Reds and everything in between.

1. Image quality

The quality of the image is of course the most imporant attribute of any camera. Rather than any technical specifications, I’m talking about the aesthetic quality here: how does it feel? Does it have that elusive “cinematic” quality? Is it “filmic”? Does it remind you of certain kinds of movies?

A good place to start is to look up sample footage on YouTube, or better still Vimeo for less compression muddying the issue. If you can borrow the camera and try it out before you buy, even better. Take away some test footage and try grading it too.

2. Resolution

Resolution, the sheer number of pixels a camera can record, is part of image quality, but I include it as a separate point because I see it as more of a technical consideration than an aesthetic one. You should ask yourself what longevity you require from your films – will people still be watching them, say two or three years from now, and if so what sort of resolution might be the norm by then?

Also consider your delivery platform. If everything you shoot is going on YouTube, perhaps you don’t need more than 1080P (standard HD).

3. Dynamic Range

Dynamic range is a measure of how much contrast a camera can handle. Too small a dynamic range and you will frequently struggle with bright areas “clipping” – i.e. losing details – or dark areas getting lost in the image noise. Also, the wider the dynamic range, the more flexibility you will have in grading.

For a cinematic image, 12 stops of dynamic range is the absolute minimum, with 14 or more being ideal.

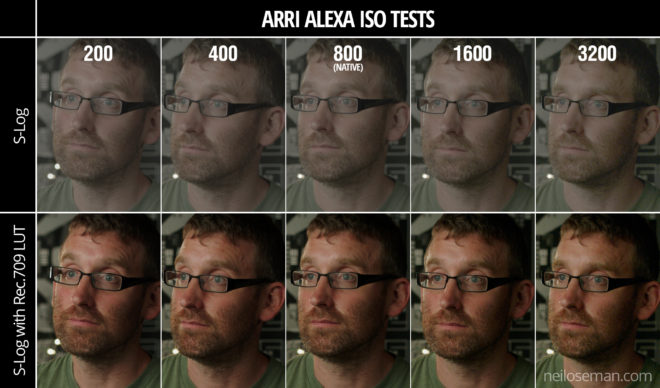

4. Maximum ISO

The ISO (International Standards Organisation) scale rates the light sensitivity of a camera. The most important thing is the native ISO, the one at which the camera is optimised to give the cleanest image with the most detail. On some cameras, setting an ISO other than the native one reduces the image quality considerably.

The higher the ISO, the less light will be required to expose an image correctly. 800 is typical these days, but many cameras go much higher than that. It is worth thinking about spending more money to get a camera with a higher native ISO, because you may save a lot of money on lighting.

5. Lens Mount

This is crucial because you may already have a collection of lenses, or you may intend to hire certain lenses, and you need to be sure that they will fit your new camera’s mount.

The Canon EF mount is extremely common and will open up a huge range of options for stills glass as well as some low-end cinema glass. The smaller MFT (micro four-thirds) mount also has a wide range of lenses.

Top-end cameras have PL mounts which take all the beautiful cinema lenses used on big movies, but only choose this route if you are willing to part with a lot of cash!

6. Form Factor

When I started in the industry, cameras were all ergonomically designed to sit on your shoulder, with a nice handgrip to the right of the lens and an EVF (electronic viewfinder) to provide a third point of stabilising contact. Nowadays cameras tend to be boxy, heavy and uncomfortable to hold without additional accessories (see below).

Again, try to gets your hands on the camera in a shop and see how it feels before you purchase. As well as handheld shooting, consider how easy it will be to rig onto dollies, sliders, gimbals, etc.

7. Required Accessories

Buying the camera body itself is unlikely to be the end of your expenditure. You will need lenses, batteries, a battery charger, cards, a card reader and almost certainly some kind of stabilising system, be it a simple shoulder rig or an electronic gimbal.

You may also want an EVF, a tripod, matte box, follow focus – the list can seem endless! Be careful to budget your essential accessories before buying the camera. Some cameras seem like bargains until you add up all the extras. Pay particular attention to the media, and to exactly what speed of media you need in order to shoot at the resolution and frame rate that you require, as this can get very expensive.

8. Codec

What file type and codec does the camera shoot? Does your editing system support that format? If not, how time-consuming will it be to convert everything?

What compression ratios does the camera support? How much hard drive space will you need to store an hour of footage at that ratio? What about ten hours, plus back-ups? Often there is a trade-off between a highly compressed format like H.264 which is light on disc space but may need converting before you can edit it, and a lightly compressed format like ProRes which burns through disc space but can be dropped straight into most editing software.