In August 2016 I was recommended to a production manager who was crewing up a small pick-ups shoot in London. The pick-ups were for Rory’s Way, or The Etruscan Smile as it was then known, a $12 million feature based on the best-selling novel of the latter name, starring Brian Cox and Thora Birch. Apparently test screenings had shown that the film’s ending wasn’t quite satisfying enough, and parts of it were to be remounted.

In August 2016 I was recommended to a production manager who was crewing up a small pick-ups shoot in London. The pick-ups were for Rory’s Way, or The Etruscan Smile as it was then known, a $12 million feature based on the best-selling novel of the latter name, starring Brian Cox and Thora Birch. Apparently test screenings had shown that the film’s ending wasn’t quite satisfying enough, and parts of it were to be remounted.

I was given a storyboard consisting of actual frame-grabs from the original version of the scene, alongside notes explaining how the action would be different. Not to give too much away, but the scene involves Brian’s character in bed, and a baby in a cot next to him. The changes simply involved Brian giving a different reaction to what the baby is doing. The bed was to be set up on stage against a blue screen, and composited into backgrounds extracted from the principal photography footage. The baby’s performance was not to be changed, so he was to be rotoscoped out of the original footage too.

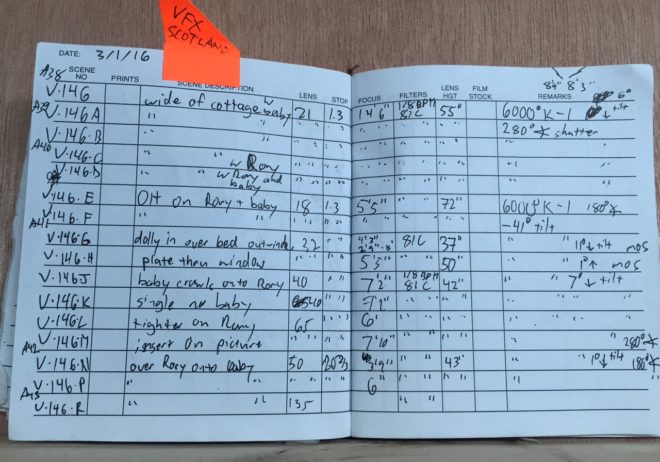

I was sent the camera report, 2nd AC’s notebook and script notes from principal photography. The crew had known that the view out of the bedroom window would be added in post, and that separate takes of the baby and Brian would be digitally combined, so they recorded plenty of information for the VFX team. Between the three documents, I had the focal length, focal distance, aperture, white balance, shutter angle, filters, lens height and tilt of every set-up in the scene.

My next step was to email the main unit DP, who was none other than Javier Aguirresarobe, ASC, AE – the man behind the lens on Thor: Ragnarok, Nicole Kidman vehicle The Others, two of the Twilight films, and Woody Allen’s Vicky Cristina Barcelona. Needless to say, I was honoured to be recreating the work of such an experienced cinematographer.

Javier told me that he had shot with Arri/Zeiss Master Primes, and explained the feel and colour of lighting he had been going for. He had used an 81C (coral) filter to warm up the image a little, and a 1/8th Black Promist for diffusion.

After that, I sat down over coffee with Ben Millar, my gaffer. We analysed the footage from principal photography and reverse-engineered the lighting. I say “we”; it was mostly Ben. This is why a DP hires a good gaffer!

After that, I sat down over coffee with Ben Millar, my gaffer. We analysed the footage from principal photography and reverse-engineered the lighting. I say “we”; it was mostly Ben. This is why a DP hires a good gaffer!

The pick-ups shoot was a single day. The afternoon before, the director and the camera department convened at the studio. The plan was to go through each of the set-ups using a stand-in in the bed. For each set-up, we first used the camera logs and script notes to put on the correct lens and filters, and set the sticks to the right height and tilt. Then, with a print-out of the original shot taped underneath the monitor, we nudged the camera around until we had the closest possible match in framing. This done, ACs Max Quinton and Bex Clives marked the tripod position on the floor with tape, writing the lens length, height, filters etc. on the tape itself to make things super-efficient the next day.

On the morning of the shoot, the lighting department had two or three hours to set up before Brian was called. We used mostly Kinoflos, with a lot of flags to represent window frames through which light sources had been shining on the original set. The VFX supervisor Stephen Coren and I checked the histograms on the monitor to ensure the blue screen was lit evenly and to the level he required.

We were ready to roll in plenty of time, and things went more or less to plan, with the addition of an extra shot or two. The editorial team were in the next room, checking our shots against the original material, and they reported that all was well.

We finished up with a single wide night interior shot for an earlier scene in the movie. This was an interesting one, because we had to extrapolate the lighting for the whole room from a single close-up that had been shot in principal photography. Our wide shot, recorded entirely against blue, would be dropped into a wide shot from principal – a daylight wide shot, that would be digitally painted and retimed for night.

At the time of writing, Rory’s Way has just hit UK cinemas, but I have yet to see it. For all I know it might have been re-edited again, but hopefully my shots are still in there! Either way, it was a fascinating exercise to analyse and reproduce the work of a top cinematographer.