Shortly before Christmas, while browsing the secondhand books in the corner of an obscure Herefordshire garden centre, I came across a small blue hardback called The Tricks of Light and Colour by Herbert McKay. Published in 1947, the book covered almost every aspect of light you could think of, from the inverse square law to camouflage and optical illusions. What self-respecting bibliophile cinematographer could pass that up?

Shortly before Christmas, while browsing the secondhand books in the corner of an obscure Herefordshire garden centre, I came across a small blue hardback called The Tricks of Light and Colour by Herbert McKay. Published in 1947, the book covered almost every aspect of light you could think of, from the inverse square law to camouflage and optical illusions. What self-respecting bibliophile cinematographer could pass that up?

Here are some quite-interesting things about light which the book describes…

1. SPHERES ARE THE KEY to understandING the inverse square law.

Any cinematographer worth their salt will know that doubling a subject’s distance from a lamp will quarter their brightness; tripling their distance will cut their brightness to a ninth; and so on. This, of course, is the inverse square law. If you struggle to visualise this law and why it works the way it does, The Tricks of Light and Colour offers a good explanation.

[Think] of light being radiated from… a mere point. Light and heat are radiated in straight lines and in all directions [from this point]. At a distance of one foot from the glowing centre the whole quantity of light and heat is spread out over the surface of a sphere with a radius of one foot. At a distance of two feet from the centre it is spread over the surface of a sphere of radius two feet. Now to find an area we multiply two lengths; in the case of a sphere both lengths are the radius of the sphere. As both lengths are doubled the area is four times as great… We have the same amounts of light and heat spread over a sphere four times as great, and so the illumination and heating effect are reduced to a quarter as great.

2. MIRAGES ARE DUE TO Total internal reflection.

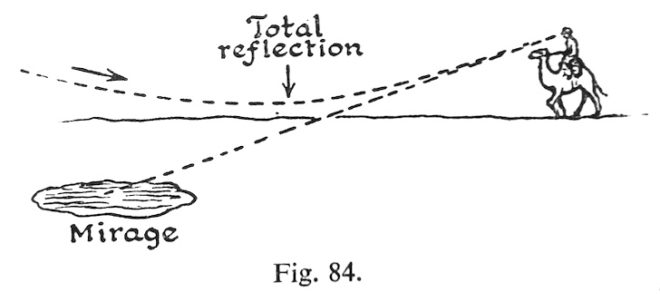

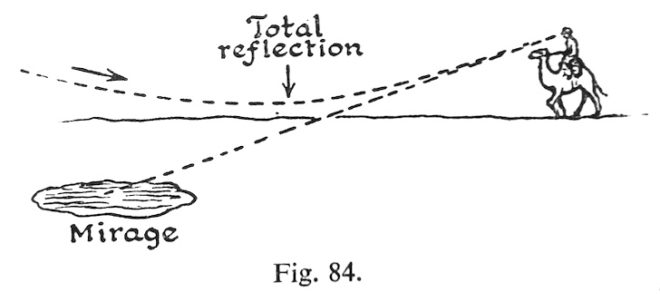

This is one of the things I dimly remember being taught in school, which this book has considerably refreshed me on. When light travels from one transparent substance to another, less dense, transparent substance, it bends towards the surface. This is called refraction, and it’s the reason that, for example, streams look shallower than they really are, when viewed from the bank. If the first substance is very dense, or the light ray is approaching the surface at a glancing angle, the ray might not escape at all, instead bouncing back down. This is called total internal reflection, and it’s the science behind mirages.

The heated sand heats the air above it, and so we get an inversion of the density gradient: low density along the heated surface, higher density in the cooler air above. Light rays are turned down, and then up, so that the scorched and weary traveller sees an image of the sky, and the images looks like a pool of cool water on the face of the desert.

3. Pinhole images pop up in unexpected places.

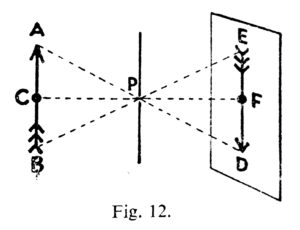

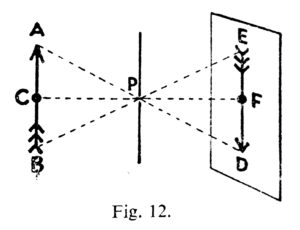

Most of us have made a pinhole camera at some point in our childhood, creating an upside-down image on a tissue paper screen by admitting light rays through a tiny opening. Make the opening bigger and the image becomes a blur, unless you have a lens to focus the light, as in a “proper” camera or indeed our eyes. But the pinhole imaging effect can occur naturally too. I’ve sometimes lain in bed in the morning, watching images of passing traffic or flapping laundry on a line projected onto my bedroom ceiling through the little gap where the curtains meet at the top. McKay describes another example:

One of the prettiest examples of the effect may be seen under trees when the sun shines brightly. The ground beneath a tree may be dappled with circles of light, some of them quite bright… When we look up through the leaves towards the sun we may see the origin of the circles of light. We can see points of light where the sun shines through small gaps between the leaves. Each of these gaps acts in the same way as a pinhole: it lets through rays from the sun which produce an image of the sun on the ground below.

4. The sun isn’t a point source.

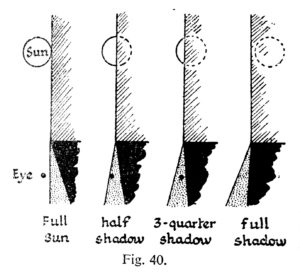

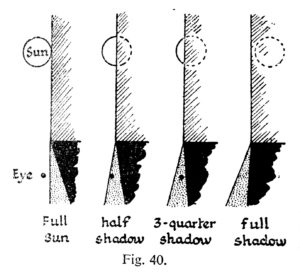

“Shadows are exciting,” McKay enthuses as he opens chapter VI. They certainly are to a cinematographer. And this cinematographer was excited to learn something about the sun and its shadow which is really quite obvious, but I had never considered before.

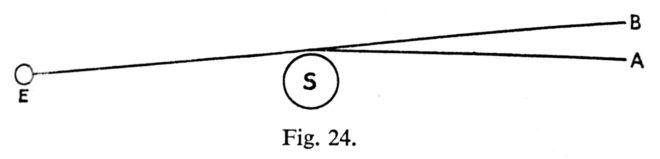

Look at the shadow of a wall. Near the base, where the shadow begins, the edge of the shadow is straight and sharp… Farther out, the edge of the shadow gets more and more fuzzy… The reason lies of course in the great sun itself. The sun is not a mere point of light, but a globe of considerable angular width.

The accompanying illustration shows how you would see all, part or none of the sun if you stood in a slightly different position relative to the hypothetical wall. The area where none of the sun is visible is of course in full shadow (umbra), and the area where the sun is partially visible is the fuzzy penumbra (the “almost shadow”).

5. Gravity bends LIGHT.

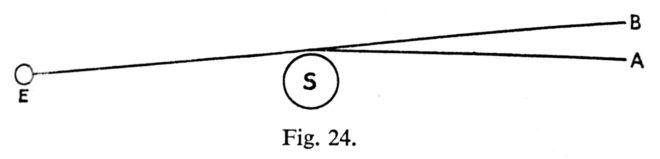

Einstein hypothesised that gravity could bend light rays, and observations during solar eclipses proved him right. Stars near to the eclipsed sun were seen to be slightly out of place, due to the huge gravitational attraction of the sun.

The effect is very small; it is too small to be observed when the rays pass a comparatively small body like the moon. We need a body like the sun, at whose surface gravity is 160 or 170 times as great as at the surface of the moon, to give an observable deviation…. The amount of shift depends on the apparent nearness of a star to the sun, that is, the closeness with which the rays of light from the star graze the sun. The effect of gravity fades out rapidly, according to the inverse square law, so that it is only near the sun that the effects can be observed.

6. Light helped us discover helium.

Sodium street-lamps are not the most pleasant of sources, because hot sodium vapour emits light in only two wave-lengths, rather than a continuous spectrum. Interestingly, cooler sodium vapour absorbs the same two wave-lengths. The same is true of other elements: they emit certain wave-lengths when very hot, and absorb the same wave-lengths when less hot. This little bit of science led to a major discovery.

The sun is an extremely hot body surrounded by an atmosphere of less highly heated vapours. White light from the sun’s surfaces passes through these heated vapours before it reaches us; many wave-lengths are absorbed by the sun’s atmosphere, and there is a dark line in the spectrum for each wave-length that has been absorbed. The thrilling thing is that these dark lines tell us which elements are present in the sun’s atmosphere. It turned out that the lines in the sun’s spectrum represented elements already known on the earth, except for one small group of lines which were ascribed to a hitherto undetected element. This element was called helium (from helios, the sun).

7. Moonlight is slightly too dim for colours.

Our retinas are populated by two different types of photoreceptors: rods and cones. Rods are much more sensitive than cones, and enable us to see in very dim light once they’ve had some time to adjust. But rods cannot see colours. This is why our vision is almost monochrome in dark conditions, even under the light of a full moon… though only just…

The light of the full moon is just about the threshold, as we say, of colour vision; a little lighter and we should see colours.

8. MAGIC HOUR can be longer than an hour.

We cinematographers often think of magic “hour” as being much shorter than an hour. When prepping for a dusk-for-night scene on The Little Mermaid, I used my light meter to measure the length of shootable twilight. The result was 20 minutes; after that, the light was too dim for our Alexas at 800 ISO and our Cooke S4 glass at T2. But how long after sunset is it until there is literally no light left from the sun, regardless of how sensitive your camera is? McKay has this to say…

Twilight is partly explained as an effect of diffusion. When the sun is below the horizon it still illuminates particles of dust and moisture in the air. Some of the scattered light is thrown down to the earth’s surface… Twilight ends when the sun is 17° or 18° below the horizon. At the equator [for example] the sun sinks vertically at the equinoxes, 15° per hour; so it sinks 17° in 1 hour 8 minutes.

9. Why isn’t Green a primary colour in paint?

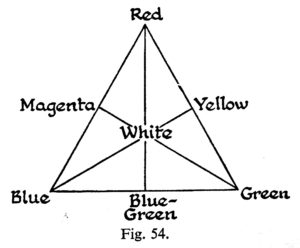

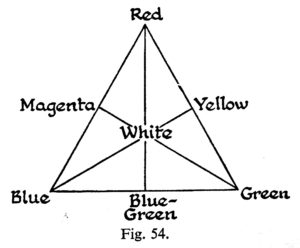

And finally, the answer to something that bugged me during my childhood. When I was a small child, daubing crude paintings of stick figures under cheerful suns, I was taught that the primary colours are red, blue and yellow. Later I learnt that the true primary colours, the additive colours of light, are red, blue and green. So why is it that green, a colour that cannot be created by mixing two other colours of light, can be created by mixing blue and yellow paints?

When white light falls on a blue pigment, the pigment absorbs reds and yellows; it reflects blue and also some green. A yellow pigment absorbs blue and violet; it reflects yellow, and also some red and green which are the colours nearest to it in the spectrum. When the two pigments are mixed it may be seen that all the colours are absorbed by one or other of the components except green.

If you’re interested in picking up a copy of The Tricks of Light and Colour yourself, there is one on Amazon at the time of writing, but it will set you back £35. Note that Herbert McKay is not to be confused with Herbert C. McKay, an American author who was writing books about stereoscopic photography at around the same time.

Yesterday I took a trip to The Tate Britain to see what I could learn about light and composition from the world of traditional art. My background is more technical than fine art, so this world is quite new to me. Within quarter of an hour of arriving, I had fallen in love with the work of JMW Turner. The way this man captured the natural moods of light and weather is breathtaking.

Yesterday I took a trip to The Tate Britain to see what I could learn about light and composition from the world of traditional art. My background is more technical than fine art, so this world is quite new to me. Within quarter of an hour of arriving, I had fallen in love with the work of JMW Turner. The way this man captured the natural moods of light and weather is breathtaking.