I’m certainly glad you could join me today. It’s a fantastic day here and I hope it is wherever you’re at. Are you ready to read a fantastic little blog post? Good, then let’s get started.

I’m certainly glad you could join me today. It’s a fantastic day here and I hope it is wherever you’re at. Are you ready to read a fantastic little blog post? Good, then let’s get started.

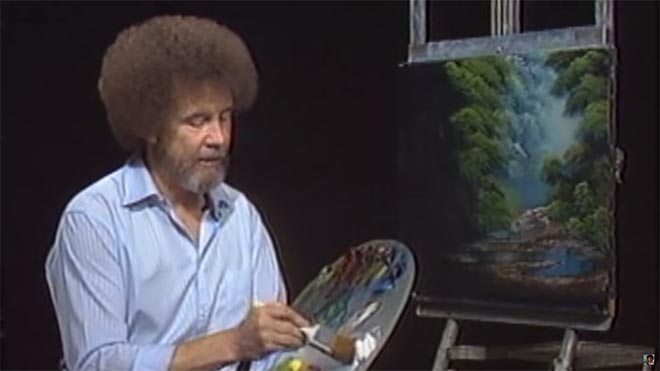

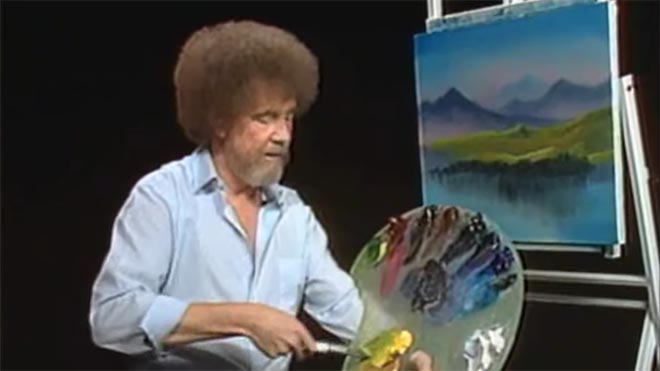

For twelve years, across 400 episodes, Bob Ross entertained all generations of Americans with his public access TV series, The Joy of Painting. Although he floated up to join the happy little clouds in 1995, in recent years YouTube and Twitch have brought his shows to a new audience, of which I am a humble member. Bob’s hypnotic, soft-spoken voice, his unfailingly positive attitude, and the magical effects of his wet-on-wet oil-painting technique make his series calming, comforting and captivating in equal measure.

Having watched every episode at least twice now, I’ve noticed several nuggets of Bob Ross wisdom that apply just as well to cinematography as they do to painting.

1. “The more plains you have in your painting, the more depth it has… and that’s what brings the happy buck.”

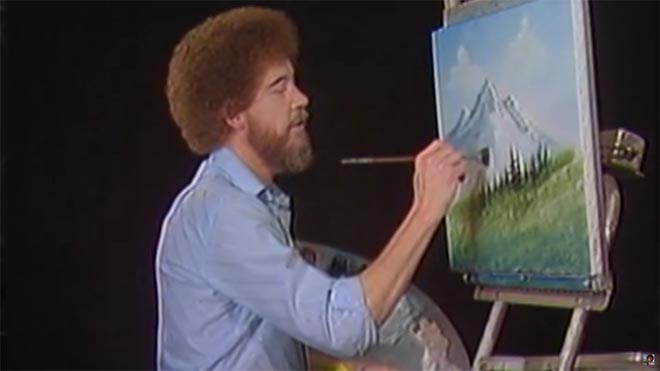

Bob always starts with the background of his scene and paints forward: first the sky with its happy little clouds; then often some almighty mountains; then the little footy hills; some trees way in the distance, barely more than scratches on the canvas; then perhaps a lake, its reflections springing forth impossibly from Bob’s brush; the near bank; and some detailed trees and bushes in the foreground, with a little path winding through them.

Bob always starts with the background of his scene and paints forward: first the sky with its happy little clouds; then often some almighty mountains; then the little footy hills; some trees way in the distance, barely more than scratches on the canvas; then perhaps a lake, its reflections springing forth impossibly from Bob’s brush; the near bank; and some detailed trees and bushes in the foreground, with a little path winding through them.

Just as with landscape painting, depth is tremendously important in cinematography. Creating a three-dimensional world with a monoscopic camera is a big part of a DP’s job, which starts with composition – shooting towards a window, for example, rather than a wall – and continues with lighting. Depth increases production value, which makes for a happy producer and a happy buck for you when you get hired again.

2. “As things get further away from you in a landscape, they get lighter in value.”

Regular Joy of Painting viewers soon notice that the more distant layers of Bob’s paintings use a lot more Titanium White than the closer ones. Bob frequently explains that each layer should be darker and more detailed than the one behind it, “and that’s what creates the illusion of depth”.

Distant objects seem lighter and less contrasty because of a phenomenon called aerial perspective, basically atmospheric scattering of light. As a DP, you can simulate this by lighting deeper areas of your frame brightly, and keeping closer areas dark. This might be achieved by setting up a flag to provide negative fill to an object in the foreground, or by placing a battery-powered LED fixture at the end of a dark street. The technique works for night scenes and small interiors, just as well as daytime landscapes, even though aerial perspective would never occur there in real life. The viewer’s brain will subconsciously recognise the depth cue and appreciate the three-dimensionality of the set much more.

3. “Don’t kill the little misty area; that’s your separator.”

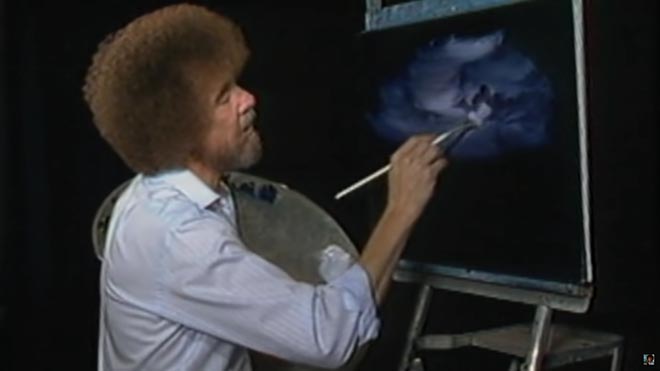

After completing each layer, particularly hills and mountains, Bob takes a clean, dry brush and taps gently along the bottom of it. This has a blurring and fading effect, giving the impression that the base of the layer is dissolving into mist. When he paints the next layer, he takes care to leave a little of this misty area showing behind it.

We DPs can add atmos (smoke) to a scene to create separation. Because there will be more atmos between the lens and a distant object than between the lens and a close object, it really aids the eye in identifying different plains. That makes the image both clearer and more aesthetically pleasing. Layers can also be separated with backlight, or a differentiation of tones or colours.

4. “You need the dark in order to show the light.”

Hinting at the tragedy in his own life, Bob often underlines the importance of playing dark tones against light ones. “It’s like in life. Gotta have a little sadness once in a while so you know when the good times come,” he wisely remarks, as he taps away at the canvas with his fan-brush, painting in the dark rear leaves of a tree. Then he moves onto the lighter foreground leaves, “but don’t kill your dark areas,” he cautions.

If there’s one thing that makes a cinematic image, it’s contrast. It can be very easy to over-light a scene, and it’s often a good idea to try turning a fixture or two off to see if the mood is improved. However bright or dark your scene is, where you don’t put light is just as important as where you do. Flagging a little natural light, blacking out a window, or removing the bubble from a practical can often add a nice bit of shape to the image.

5. “Maybe… maybe… maybe… Let’s DROP in an almighty tree.”

As the end of the episode approaches, and the painting seems complete, Bob has a habit of suddenly adding a big ol’ tree down one or both sides of the canvas. Since this covers up background layers that have been carefully constructed earlier in the show, Bob often gets letters complaining that he has spoilt a lovely painting. “Ruined!” is the knowing, light-hearted comment of the modern internet viewer.

The function of these trees is to provide a foreground framing element which anchors the side of the image. I discussed this technique in my article on composing a wide shot. A solid, close object along the side or base of the frame makes the image much stronger. It gives a reason for the edge of the frame to be there rather than somewhere else. As DPs, we may not be able to just paint a tree in, but there’s often a fence, a pillar, a window frame, even a supporting artist that we can introduce to the foreground with a little tweaking of the camera position.

The ol’ clock on the wall tells me it’s time to go, so until next time: happy filming, and God bless, my friend.

If you’re keen to learn more about cinematography, don’t forget I have an in-depth course available on Udemy.