The seventh instalment in the Mission: Impossible franchise was originally scheduled for release this July. It’s since been pushed back to next September, which is a minor shame because it means there will be no release in 2021 to mark the quarter of a century since Tom Cruise first chose to accept the mission of bringing super-spy Ethan Hunt to the big screen.

The seventh instalment in the Mission: Impossible franchise was originally scheduled for release this July. It’s since been pushed back to next September, which is a minor shame because it means there will be no release in 2021 to mark the quarter of a century since Tom Cruise first chose to accept the mission of bringing super-spy Ethan Hunt to the big screen.

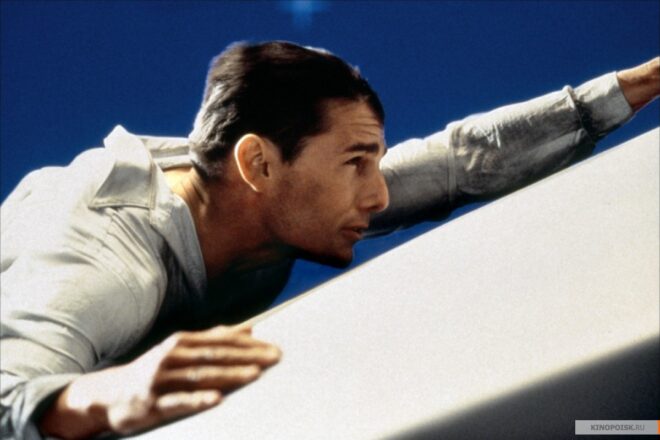

Today, 1996’s Mission: Impossible is best remembered for two stand-out sequences. The first, fairly simple but incredibly tense, sees Cruise descend on a cable into a high-security vault where even a single bead of sweat will trigger pressure sensors in the floor.

The second, developing from the unlikely to the downright ludicrous, finds Cruise battling Jon Voight atop a speeding Channel Tunnel train, a fight which continues on the skids of a helicopter dragged along behind the Eurostar, ending in an explosion which propels Cruise (somehow unscathed) onto the rear of the train.

It is the second of those sequences which is a landmark in visual effects, described by Cinefex magazine at the time as “the dawn of virtual sets”.

“In Mission: Impossible, we took blue-screen elements of actors and put them into believable CG backgrounds,” said VFX supervisor John Knoll of Industrial Light and Magic. Building on his work on The Abyss and Terminator 2, Knoll’s virtual tunnel sets would one day lead to the likes of The Mandalorian – films and TV shows shot against LED screens displaying CG environments.

Which is ironic, given that if Tom Cruise was remaking that first film today, he would probably insist on less trickery, not more, and demand to be strapped to the top of a genuine speeding Eurostar.

The Channel Tunnel had only been open for two years when Mission: Impossible came out, and the filmmakers clearly felt that audiences – or at least American audiences – were so unfamiliar with the service that they could take a number of liberties in portraying it. The film’s tunnel has only a single bore for both directions of travel, and the approaching railway line was shot near Glasgow.

That Scottish countryside is one of the few real elements in the sequence. Another is the 100ft of full-size train that was constructed against a blue-screen to capture the lead actors on the roof. To portray extreme speed, the crew buffeted the stars with 140mph wind from a parachute-training fan.

Many of the Glasgow plates were shot at 12fps to double the apparent speed of the camera helicopter, which generally flew at 80mph. But when the plate crew tried to incorporate the picture helicopter with which Jean Reno’s character chases the train, the under-cranking just looked fake, so the decision was taken to computer-generate the aircraft in the vast majority of the shots.

The train is also CGI, as are the tunnel entrance and some of its surroundings, and of course the English Channel is composited into the Glaswegian landscape. Once the action moves inside the tunnel, nothing is real except the actors and the set-pieces they’re clinging to.

“We cheated the scale to keep it tight and claustrophobic,” said VFX artist George Hull, admitting that the helicopter could not have fitted in such a tunnel in reality. “The size still didn’t feel right, so we went back and added recognisable, human-scale things such as service utility sheds and ladders.”

Overhead lights spaced at regular intervals were simulated for the blue-screen work. “When compositing the scenes into the CG tunnel months later, we could marry the environment by timing those interactive lights to the live-action plates,” explained Hull.

Employing Alias for modelling, Softimage for animation, RenderMan for rendering, plus custom software like ishade and icomp, ILM produced a sequence which, although it wasn’t completely convincing even in 1996, is still exciting.

Perhaps the best-looking part is the climactic explosion, which was achieved with a 1/8th scale miniature propelled at 55mph through a 120ft tunnel model. (The runaway CGI which followed Jurassic Park’s 1993 success wisely stayed away from explosions for many years, as their dynamics and randomness made them extremely hard to simulate on computers of the time.)

Knoll went on to supervise the Star Wars prequels’ virtual sets (actually miniatures populated with CG aliens), and later Avatar and The Mandalorian. Meanwhile, Cruise pushed for more and more reality in his stunt sequences as the franchise went on, climbing the Burj Khalifa for Ghost Protocol, hanging off the side of a plane for Rogue Nation, skydiving and flying a helicopter for Fallout, and yelling at the crew for Mission: Impossible 7.

At least, I think that last one was real.