While in Japan recently, I was finally able to get hold of that country’s version of my 2005 feature film, Soul Searcher. I thought this would be a good opportunity to talk a little bit about international distribution and the mysterious M&E mix.

The story of an ordinary guy who gets trained to be the new Grim Reaper, Soul Searcher was picked up for distribution by a small UK company called Wysiwyg Films (now defunct). After releasing it on DVD in the UK, they sold all the foreign rights (much to my chagrin) to American sales agents Loose Cannon. Loose Cannon put out a US DVD, aiming to misleadingly tap the horror market by adding a splash of blood to the cover art, along with a stock photo of a random hooded guy with glowing eyes.

Loose Cannon then sub-sub-licensed the rights to five other territories: Benelux, Russia, Argentina, Thailand and Japan. Russian pirates hilariously dubbed the film into their own language (see some clips here), but the only territory to officially dub rather than subtitle the movie was Japan.

Presumably because of the film’s numerous martial arts fights, the Japanese distributors paid more for the film than any other country: $24,750. I know this from the Loose Cannon sales reports that were eventually forwarded to me by Wysiwyg. The only reason I know anything else about the Japanese release is from extensive googling (using the actors’ names as search terms proved most fruitful) which led me to the Amazon.jp page for the DVD a few years ago.

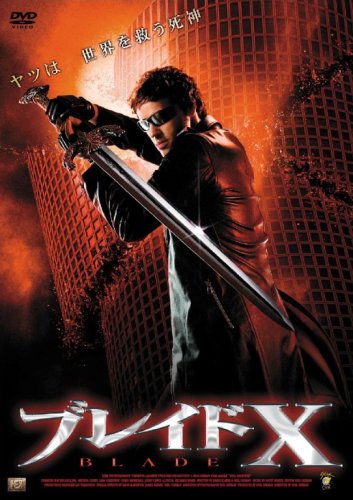

At first I thought I’d made a mistake. The cover art displayed on the page was completely new to me, showing an unfamiliar man holding a huge sword (a weapon never used by Soul Searcher’s hero). Beneath that was the title, in both Japanese and English: Blade X. It was only after Google Translating the page that the customer reviews confirmed this was indeed my very own Soul Searcher. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the reviews complained of the film’s lack of Wesley Snipes, the lack of correlation between the movie’s scythe-wielding hero and the cover’s sword-bearing imposter, plus many other flaws that are common to the English version!

Sadly, this is how low budget film sales work. The distributors know that the films are unlikely to generate much positive word of mouth, so they resort to tricking consumers into buying them with misleading covers and references to more successful films.

Anyway, when I saw that Amazon’s tech specs listed a Japanese audio track, I was desperate to get my hands on the DVD. But I could never find a seller who would import it for less than an eye-watering £40, so I waited, and in June this year I finally visited Japan and bought a copy.

But how does dubbing work? Well, amongst the delivery materials that a sales agent will require when you sell them your film will be an M&E mix – that’s Music and Effects. What this means is that you supply a version of the film which contains music, sound effects, foley, atmospheres, everything except the dialogue. This is one of the reasons for the existence of foley (footsteps, clothing rustles and other mundane sounds added to the film in postproduction); if you relied on the footsteps recorded along with the dialogue on set, those footsteps would disappear when you muted the dialogue tracks to produce the M&E mix.

It’s always worth running off an M&E version when mixing a feature, whatever you feel its chances of achieving distribution are. Trying to create an M&E track after the fact, when the mixer has moved on to other projects, the source files may no longer exist, etc, etc, is likely to be a real headache. Instead, take five minutes in your mixing session to mute the dialogue tracks and bounce it out.

Along with the M&E mix, sales agents will require a dialogue list – essentially a transcription of the film, so it can be translated ready for dubbing or subtitling.

The following video compares some clips from Soul Searcher, showing the original English versions, followed by the M&E track, then the Japanese dub.

The Japanese distributors made a good job of dubbing Soul Searcher. As far as I can tell, the voice cast seem to give decent performances, and the mixer has blended everything carefully together. I wonder how much this dub cost them? Undoubtedly, factoring in the manufacturing and advertising costs, and the $24,750 they paid to Loose Cannon for the rights, they will have spent more on the film than my investors and I did in making it (£28,000).

If you want to know more about distribution contracts, check out my post on what to look for in one, and for the full story of Soul Searcher’s financing, expenditure, and distribution revenue, look no further than this exhaustive, no-holds-barred video…