Exciting title, right? It’s not the glamorous side of a DP’s job, but enabling a scene to be shot quickly is a skill which definitely has its place, as long as you balance it with creative and technical quality, of course.

Exciting title, right? It’s not the glamorous side of a DP’s job, but enabling a scene to be shot quickly is a skill which definitely has its place, as long as you balance it with creative and technical quality, of course.

When a scene has been blocked and the cast have gone off to have their make-up and costuming finished, and even the director has disappeared to make plans for future scenes, the DP is left on the set to light it. Though there is always time pressure on a film, it is at a minimum during this initial lighting period (usually for the wide shot). But once the wide is in the can, the DP is expected to move quickly when tweaking lights for the coverage, as all the cast and crew are standing around waiting for you.

So a wise DP always thinks ahead to the coverage, setting up as much as possible for it concurrently with the wide, or better still sets up the wide’s lighting so that it works for the coverage too.

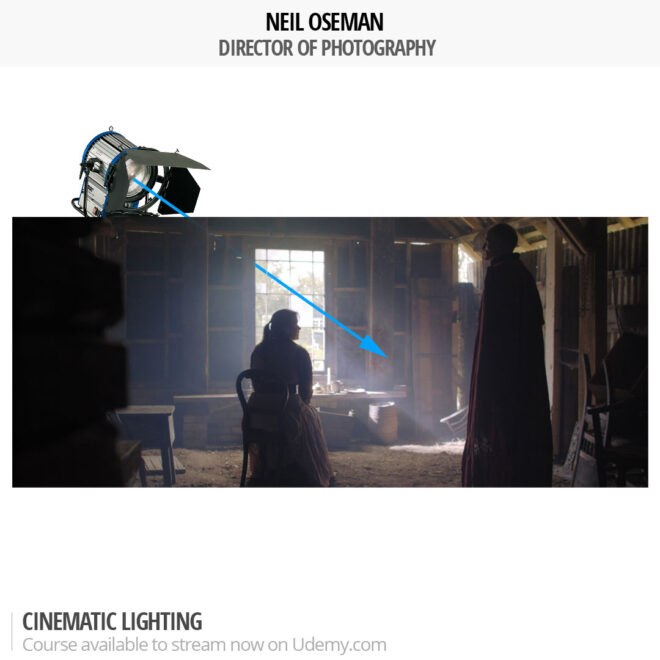

If we boil things right down, light looks best when it comes in from the side or the back, not the front. A common technique is to block and/or light the scene so that the main light source, be that the real sun, a window or an artificial source, is behind the cast in the wide. Let’s imagine this from the top down with the camera at 6 o’clock, the key light at 12 o’clock, and the actors in the centre.

Because of the 180º Rule, otherwise known as the Line of Action, the camera positions for the coverage are likely to all be on the bottom half of the clock face between 3 o’clock and 9 o’clock. At either of those two positions the 12 o’clock key light is now coming in from the side, so your image still has mood.

Another common set-up is cross-backlight. Here you would have two lights, one at about 10:30 and the other at 1:30. These give a three-quarter backlight in the wide and a three-quarter key light in the singles.

Something basic to avoid is lights actually being in shot when you move to a new camera position. Early in my career I used to put all my lamps on stands because I didn’t know any better (or have any rigging kit to do anything else), but that means you’re forever moving them. Much better to rig things to the ceiling, or to position them outside the room shining in through doors and windows.

Practicals lights are really helpful too, because you can get them in shot with impunity. You can save hours of pain on set by collaborating with the art department in pre-production to make sure there are enough practicals to justify light from all the angles you might need it. Put them all on dimmers and use a fast lens or high ISO and you may well find that when you change camera position you only need to dim down the frontal ones and bring up the back ones to get the shot looking nice.

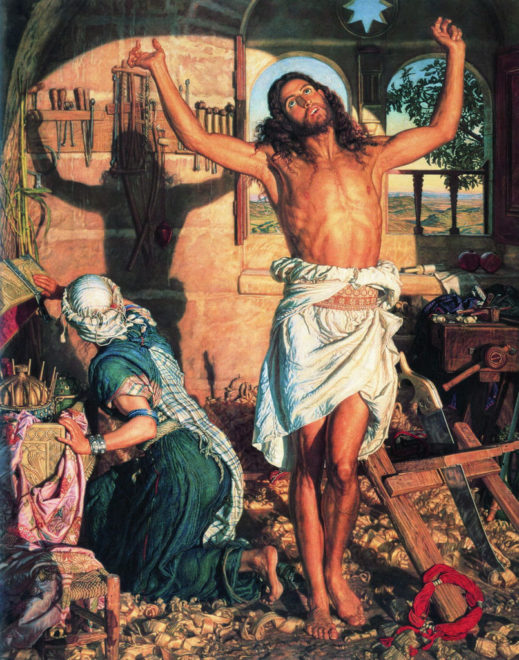

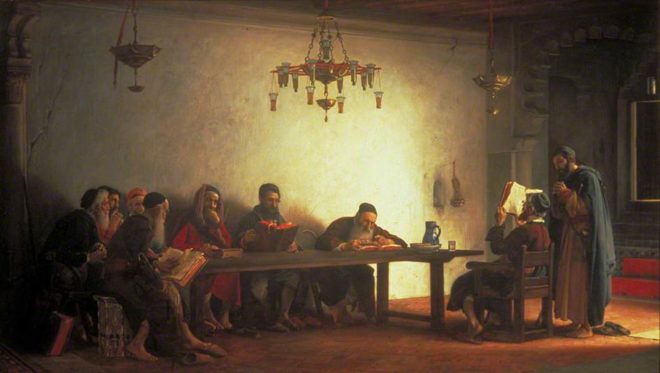

I once had to light a scene in a medieval chapel for a horror film called Heretiks. The master was a Steadicam shot moving 360º around the set. The gaffer and I invested the time beforehand to rig numerous 300W and 650W tungsten fresnels around the tops of all the walls, connected to dimmers. (The light was motivated by numerous candles.) With a bit of practice the gaffer and sparks were able to dim each lamp as the camera passed in front of it – to avoid camera shadows and the flat look of front light – and bring them back up afterwards, so there was always a wrapping backlight. A convenient side effect was that when we moved onto conventional coverage we could light shots in seconds by turning a few dimmers down or off and others up.

DP Benedict Spence used a similar principle on the recent BBC series This is Going to Hurt; he had 250 Astera Titan tubes built into the hospital set. While this was time-consuming and expensive upfront, it meant that shots could be lit very quickly by making a few tweaks at a lighting desk. And since the tubes looked like fluorescent strip-lights, there was never any problem with getting them in shot.

Once you start shooting a scene it’s important to keep up the pace so that the cast can stay in the zone. Spending extra time in prep or when lighting the wides will pay dividends in faster coverage, giving the director more time to get the best performances and to tell the story, which is ultimately what it’s all about.