This is the latest in my series about analogue photography. Previously, I’ve covered the science behind film capture, and how to develop your own black-and-white film. Now we’ll proceed to the next step: taking your negative and producing a print from it. Along the way we’ll discover the analogue origins of Photoshop’s dodge and burn tools.

Contact printing

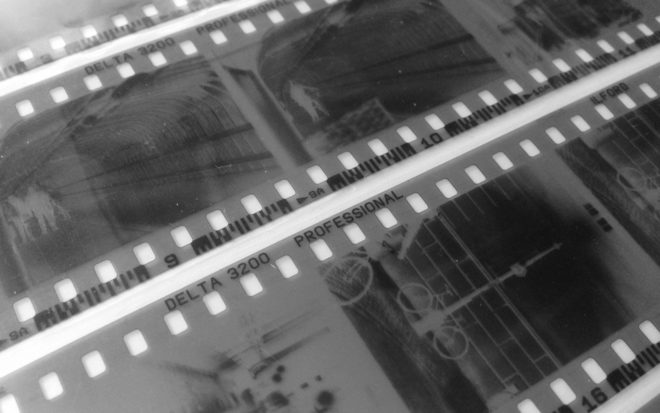

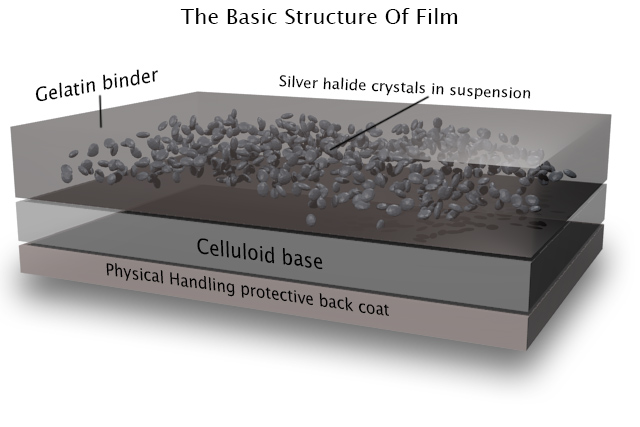

To briefly summarise my earlier posts, we’ve seen that photographic emulsion – with the exception of colour slide film – turns black when exposed to light, and remains transparent when not. This is how we end up with a negative, in which dark areas correspond to the highlights in the scene, and light areas correspond with the shadows.

The simplest way to make a positive print from a negative is contact-printing, so called because the negative is placed in direct contact with the photographic printing paper. This is typically done in a spring-loaded contact printing frame, the top of which is made of glass. You shine light through the glass, usually from an enlarger – see below – for a measured period of time, determined by trial and error. Where the negative is dark (highlights) the light can’t get through, and the photographic emulsion on the paper remains transparent, allowing the white paper base to show through. Where the negative is transparent (shadows) the light passes through, and the emulsion – once developed and fixed in the same way as the original film – turns black. Thus a positive image is produced.

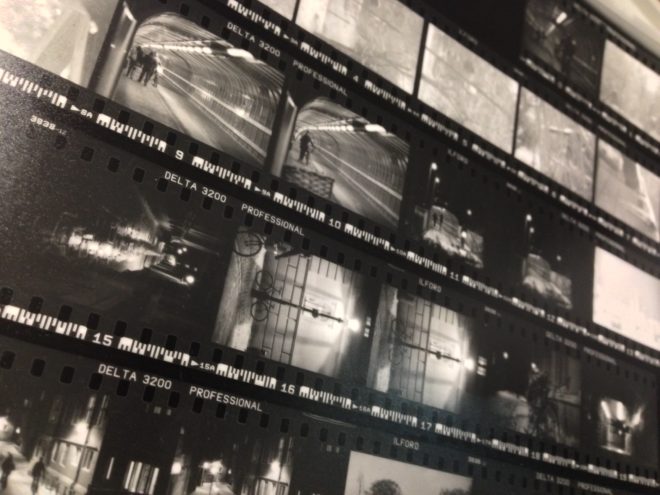

Normally you would contact-print multiple strips of negative at the same time, perhaps an entire roll of film’s worth, if your paper is large enough to fit them all. Then you can examine them through a loupe to decide which ones are worth enlarging. You have probably seen contact sheets, complete with circled images, stars and arrows indicating which frames the photographer or picture editor likes, where they might crop it, and which areas need doctoring. In fact, contact sheets are so aesthetically pleasing that it’s not uncommon these days for graphic designers to create fake digital ones.

The correct exposure time for a contact print can be found by exposing the whole sheet for, say, ten seconds, then covering a third of it with a piece of card, exposing it for another ten seconds, then covering that same third plus another third and exposing it for ten seconds more. Once developed, you can decide which exposure you like best, or try another set of timings.

Making an enlargement

Contact prints are all well and good, but they’re always the same size as the camera negative, which usually isn’t big enough for a finished product, especially with 35mm. This is where an enlarger comes in.

An enlarger is essentially a projector mounted on a stand. You place the negative of your chosen image into a drawer called the negative carrier. Above this is a bulb, and below it is a lens. When the bulb is turned on, light shines through the negative, and the lens focuses the image (upside-down of course) onto the paper below. By adjusting the height of the enlarger’s stand, you can alter the size of the projected image.

Just like a camera lens, an enlarger’s lens has adjustable focus and aperture. You can scrutinise the projected image using a loupe; if you can see the grain of the film, you know that the image is sharply focused.

The aperture is marked in f-stops as you would expect, and just like when shooting, you can trade off the iris size against the exposure time. For example, a print exposed for 30 seconds at f/8 will have the same brightness as one exposed for 15 seconds at f/5.6. (Opening from f/8 to f/5.6 doubles the light, or increases exposure by one stop, while halving the time cuts the light back to its original value.)

Dodging and burning

As with contact-printing, the optimum exposure for an enlargement can be found by test-printing strips for different lengths of time. This brings us to dodging and burning, which are respectively methods of decreasing or increasing the exposure time of specific parts of the image.

Remember that the printing paper starts off bright white, and turns black with exposure, so to brighten part of the image you need to reduce its exposure. This can be achieved by placing anything opaque between the projector lens and the paper for part of the exposure time. Typically a circle of cardboard on a piece of wire is used; this is known as a dodger. That’s the “lollipop” you see in the Photoshop icon. It’s important to keep the dodger moving during the exposure, otherwise you’ll end up with a sharply-defined bright area (not to mention a visible line where the wire handle was) rather than something subtle.

Let me just say that dodging is a joyful thing to do. It’s such a primitive-looking tool, but you feel like a child with a magic wand when you’re using it, and it can improve an image no end. It’s common practice today for digital colourists to power-window a face and increase its luminance to draw the eye to it; photographers have been doing this for decades and decades.

Burning is of couse the opposite of dodging, i.e. increasing the exposure time of part of the picture to make it darker. One common application is to bring back detail in a bright sky. To do this you would first of all expose the entire image in such a way that the land will look good. Then, before developing, you would use a piece of card to cover the land, and expose the sky for maybe five or ten seconds more. Again, you would keep the card in constant motion to blend the edges of the effect.

To burn a smaller area, you would cut a hole in a piece of card, or simply form your hands into a rough hole, as depicted in the Photoshop icon.

Requirements of a darkroom

The crucial thing which I haven’t yet mentioned is that all of the above needs to take place in near-darkness. Black-and-white photographic paper is less sensitive to the red end of the spectrum, so a dim red lamp known as a safe-light can be used to see what you’re doing. Anything brighter – even your phone’s screen – will fog your photographic paper as soon as you take it out of its lightproof box.

The crucial thing which I haven’t yet mentioned is that all of the above needs to take place in near-darkness. Black-and-white photographic paper is less sensitive to the red end of the spectrum, so a dim red lamp known as a safe-light can be used to see what you’re doing. Anything brighter – even your phone’s screen – will fog your photographic paper as soon as you take it out of its lightproof box.

Once your print is exposed, you need to agitate it in a tray of diluted developer for a couple of minutes, then dip it in a tray of water, then place it in a tray of diluted fixer. Only then can you turn on the main lights, but you must still fix the image for five minutes, then leave it in running water for ten minutes before drying it. (This all assumes you’re using resin-coated paper.)

Because you need an enlarger, which is fairly bulky, and space for the trays of chemicals, and running water, all in a room that is one hundred per cent lightproof, printing is a difficult thing to do at home. Fortunately there are a number of darkrooms available for hire around the country, so why not search for a local one and give analogue printing a go?