Here’s a breakdown of the lighting choices made on my little puppet film, The One That Got Away. You can watch the film over at the Virgin Media Shorts website. If you enjoy it, please use the tweet button to register your vote and help us get a place on the shortlist.

Conventional wisdom with marionettes is probably to go for very flat lighting with no backlight, to make it as difficult as possible to see the strings. But on TOTGA I wanted to embrace and celebrate the tactile, handmade look of the puppets and sets, so I chose a traditional three-point lighting scheme that imparted depth and made no effort to hide the strings.

Normally I shoot wide open – typically f1.8 – on my DSLR, but as the puppets were small the depth of field would have been ridiculously shallow at that aperture. Instead I lit the set very brightly (about 3KW of tungsten horsepower in our cramped living room – not very pleasant during a heatwave!) and stopped down to around f4.

Daylight

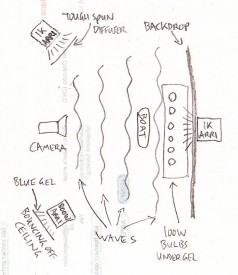

For the daylight scenes I used my three open-face tungsten Arrilites: a 1K poking over the top of the backdrop for backlight, another 1K with tough-spun diffuser off camera left for key, and an 800W bouncing off the ceiling for fill. This last lamp was gelled blue to suggest ambient skylight.

I tried to simulate the camerawork that would have been used had this been shot at sea with real actors, so:

- the camera bobs up and down in wide shots, as if Henry’s boat is being shot from another vessel;

- the camera and boat are fixed in close-ups, with the background bobbing up and down, as if we’re now shooting on a tripod in Henry’s boat.

Underwater

The underwater dream sequence was all shot dry-for-wet at 50fps for a watery slow motion. Using Magic Lantern I dialled in a cool white balance of around 2500K, and pumped in smoke to add diffusion and suggest currents. (I wished I’d use a lot more smoke, but we would have all choked to death.)

I used just two light sources: the 1K backlight, now gelled blue, and the other 1K, bounced off sheets of silver wrapping paper tacked loosely to the ceiling. This is exactly the same method I used for a scene in Ashes – flapping a piece of card at the wrapping paper makes the light ripple in a very watery way.

The underwater lighting scheme was a lot darker than the daylight one, so I opened up to around f2, giving a crazily shallow depth of field that worked nicely for this dream sequence. The mermaid’s close-ups were all shot through a CD case for an old-school soft-focus look.

I would have liked to have shot this sequence handheld, but a lack of crew meant I had to lock the camera off so I could operate the smoke machine, fan the wrapping paper and move little fish through frame.

Sunset

When Henry awakens from his dream, the fish escapes and he gives chase. Orange gels and lens flare were used to suggest the sun getting lower in the sky, until finally Henry and his quarry are silhouetted against the solar disc itself. This is a domestic 100W tungsten bulb peeking over the back wave. The only other light source is a row of six more such bulbs under a sheet of orange gel, just behind and below the first one.

As the scene moves into twilight, the first bulb is removed and the orange gel over the other six is replaced with a purple one. The 1K backlight is turned back on (possibly it would have been more realistic without, but I’m just a sucker for backlight) and some pink fill is provided by placing a sheet of Minus Green gel on the other 1K and bouncing it off a reflector.

That’s all folks. Please do tweet about the film (being sure to include the title The One That Got Away and the hashtag #VMShortsVote for it to count as a vote) and click here to watch the behind-the-scenes featurette if you missed it.