With the runaway success of the first instalment, there was no way that Universal Pictures weren’t going to make another Back to the Future, with or without creators Bob Gale and Robert Zemeckis. So after confirming that Michael J. Fox and Christopher Lloyd were willing to reprise their roles as Marty McFly and Doc Emmett Brown, the producer and director got together to thrash out story ideas.

They knew from the fan mail which had been pouring in that they had to pick up the saga where they had left off: with Doc, Marty and his girlfriend Jennifer zooming into the future to do “something about your kids!” They soon hit upon the idea of an almanac of sport results being taken from 2015 into the past by Marty’s nemesis Biff Tannen (Thomas F. Wilson), resulting in a “Biff-horrific” alternate 1985 which Marty and Doc must undo by journeying into the past themselves.

Gale’s first draft of the sequel, written up while Zemeckis was away in England shooting Who Framed Roger Rabbit?, had Biff giving the almanac to his younger self in 1967. Marty would don bell-bottom trousers and love beads to blend into the hippy culture, meet his older siblings as very young children and his mother Lorraine as an anti-war protestor, and endanger his own existence again by preventing his parents going on the second honeymoon during which he was conceived.

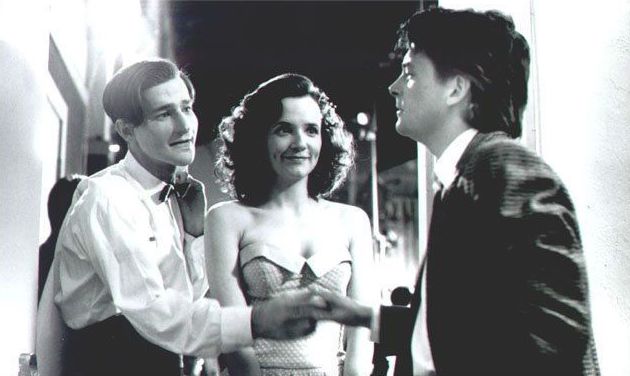

Upon returning from England and reading the draft, Zemeckis had two main notes: add a fourth act set in the Wild West, and how about 1955 again instead of 1967? “We could actually do what the audience really, really wants, which is to go back and revisit the movie they just saw,” Zemeckis later explained. “That is the thing that excited me most, this idea of seeing the same movie from a different angle.”

Adding the Wild West act ballooned the script to over two-and-a-half hours with an estimated budget of $60 million, far more than Universal wanted to spend. So Gale revised the screenplay, expanding it further with a neat point in the middle where it could be split in half. As two films, each budgeted at $35 million but shot back-to-back over 11 months, the project was much more appealing to the studio. However, it was still a bold and unusual move for Universal to green-light two sequels simultaneously, something that it’s easy to forget in these days of long-form movie franchises planned out years in advance.

A sticking point was Crispin Glover. As Marty’s father George McFly he had been a difficult actor to work with on the first film, and now he was demanding more than a ten-fold pay increase to appear in the sequels. “Crispin… asked for the same money that Michael J. Fox was receiving, as well as script approval and director approval,” according to Gale. He gave Glover’s agent two weeks to come back with a more realistic offer, but it didn’t come. Glover would not be reprising his role.

Gale accordingly made George dead in the Biff-horrific 1985, and Zemeckis employed several tricks to accomplish his other scenes. These included the reuse of footage from Part I, and hanging cheap replacement actor Jeffrey Weissman upside-down in a futuristic back brace throughout the 2015 scenes. Life casts of Glover’s face taken for the ageing effects in Part I were even used to produce prosthetic make-up appliances for Weissman so that he would resemble Glover more closely. “Oh, Crispin ain’t going to like this,” Fox reportedly remarked, and he was right. Glover would go on to successfully sue the production for using his likeness without permission, with the case triggering new Screen Actors Guild rules about likeness rights.

Make-up was a huge part of the second film, since all the main actors had to portray their characters at at least two different ages, and some played other members of the family too. A 3am start in the make-up chair was not unusual, the prosthetics became hot and uncomfortable during the long working days, and the chemicals used in their application and removal burnt the actors’ skin. “It was a true psychological challenge to retain enough concentration to approach the character correctly and maintain the performance,” said Wilson at the time.

Filming began in February 1989 with the ’55 scenes. To save time and money, only one side of the Hill Valley set – still standing on the Universal backlot – was dressed for this period. The company then shot on stage for a few weeks before returning to the backlot in March, by which time production designer Rick Carter and his team had transformed the set into a gangland nightmare to represent Biff-horrific 1985. In May the company revisited the Hill Valley set once more to record the 2015 scenes.

When the real 2015 rolled around, many were quick to compare the film’s vision of the future to reality, but Gale always knew that he would fail if he tried to make genuine predictions. “We decided that the only way to deal with it was to make it optimistic, and have a good time with it.” Microwave meals had begun to compete with home cooking in the ‘80s, so Gale invented a leap forward with the pizza-inflating food hydrator. Kids watched too much TV, so he envisaged a future in which this was taken to a ridiculous extreme, with Marty Jr. watching six channels simultaneously – not a million miles from today’s device-filled reality.

While the opening instalment of the trilogy had been relatively light on visual effects, Part II required everything from groundbreaking split-screens to flying cars and hoverboards. This last employed a range of techniques mostly involving Fox, Wilson and three other actors, plus five operators, hanging from cranes by wires. While every effort was made to hide these wires from camera – even to the extent of designing the set with a lot of camouflaging vertical lines – the film went down in VFX history as one of the first uses of digital wire removal.

But perhaps the most complex effect in the film was a seemingly innocuous dinner scene in which Marty, Marty Jr. and Marlene McFly all share a pizza. The complication was that all three roles were played by Michael J. Fox. To photograph the scene and numerous others in which cast members portrayed old and young versions of themselves, visual effects wizards Industrial Light & Magic developed a system called VistaGlide.

Based on the motion control rigs that had been used to shoot spaceships for Star Wars, the VistaGlide camera was mounted on a computer-controlled dolly. For the dinner scene, Fox was first filmed as old Marty by a human camera operator, with the VistaGlide recording its movements. Once Fox had switched to his Marty Jr. or Marlene costume and make-up, the rig could automatically repeat the camerawork while piping Fox’s earlier dialogue to a hidden earpiece so that he could speak to himself. Later the three elements were painstakingly and seamlessly assembled using hand-drawn masks and an analogue device called an optical printer.

The technically challenging Part II shoot came to an end on August 1st, 1989, as the team captured the last pieces of the rain-drenched scene in which Marty receives a 70-year-old letter telling him that Doc is living in the Old West. Four weeks later, the whole cast and crew were following Doc’s example as they began filming Part III.

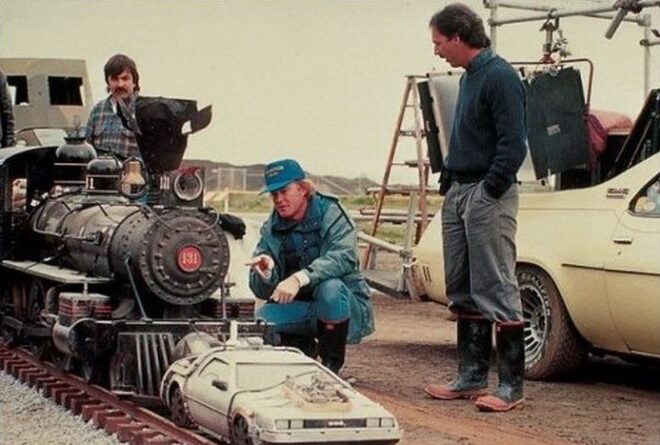

In order to have open country visible beyond the edges of 1885’s Hill Valley, the filmmakers opted to leave the Universal backlot and build a set 350 miles north in Sonora, California. The town – which had appeared in classic westerns like High Noon and Pale Rider – was chosen for its extant railway line and its genuine 19th century steam locomotive which would form a pivotal part of the plot.

Joining the cast was Mary Steenburgen as Doc’s love interest Clara. Initially unsure about the role, she was persuaded to take it by her children who were fans of the original film. “I confess to having been infatuated with her, and I think it was mutual,” LLoyd later admitted of his co-star. Though the pair never got involved, Part III’s romantic subplot did provide the veteran of over 30 films with his first on-screen kiss.

By all accounts, an enjoyable time was had by the whole cast and crew in the fresh air and open spaces of Sonora. Fox, who had simultaneously been working on Family Ties during the first two films, finally had the time to relax between scenes, even leading fishing trips to a nearby lake.

The set acquired the nickname “Club Hill Valley” as a volleyball court, mini golf and shooting range were constructed. “We had a great caterer,” recalled director of photography Dean Cundey, “but everybody would rush their meal so that they could get off to spend the rest of their lunch hour in their favourite activity.”

There was one person who was not relaxed, however: Robert Zemeckis. Part II was due for release on November 20th, about halfway through the shoot for Part III. While filming the action-packed climax in which the steam train propels the DeLorean to 88mph, the director was simultaneously supervising the sound mix for the previous instalment. After wrapping at the railway line, Zemeckis would fly to Burbank and eat his dinner on the dubbing stage while giving the sound team notes. He’d then sleep at the Sheraton Universal and get up at 4:30am to fly back to Sonora.

The train sequence had plenty of other challenges. Multiple DeLoreans had been employed in the making of the trilogy so far, including a lightweight fibreglass version that was lifted on cables or hoisted on a forklift for Part II’s flying scenes, and two off-road versions housing Volkswagen racing engines for Part III’s desert work. Another was now outfitted with railway wheels by physical effects designer Michael Lantieri. “One of the scariest things to do was the DeLorean doing the wheelie in front of the train,” he noted in 2015. “We had cables and had it hooked to the front of the train… A big cylinder would raise the front of the car.”

The film’s insurance company was unhappy about the risks of putting Michael J. Fox inside a car that could potentially derail and be crushed by the train, so whenever it was not possible to use a stunt double the action was played out in reverse; the locomotive would pull the DeLorean, and the footage would subsequently be run backwards.

The makers of Mission: Impossible 7 recently drove a full-scale mock-up of a steam locomotive off an unfinished bridge, but Back to the Future’s team opted to accomplish a very similar stunt in miniature. A quarter-scale locomotive was constructed along with a matching DeLorean, and propelled to its doom at 20mph with six cameras covering the action. Marty, of course, has returned safely to 1985 moments earlier.

Part III wrapped on January 12th, 1990 and was released on May 25th, just six months after Part II. Although each instalment made less money than its predecessor, the trilogy as a whole grossed almost $1 billion around the world, about ten times its total production cost. The franchise spawned a theme park ride, an animated series, comics and most recently a West End musical.

But what about Part IV? Thomas F. Wilson is a stand-up comedian as well as an actor, and on YouTube you can find a track of his called “Biff’s Questions Song” which humorously answers the most common queries he gets from fans. The penultimate chorus reveals all: “Do you all hang out together? No we don’t / How’s Crispin Glover? Never talk to him / Back to the Future IV? Not happening / Stop asking me the question!”