What does a cinematographer’s working day look like? Here’s a snapshot of last Wednesday, the fifth shooting day of six on a short film in south London. It’s a split day, with one daylight and one night scene scheduled, so the call time is 2pm.

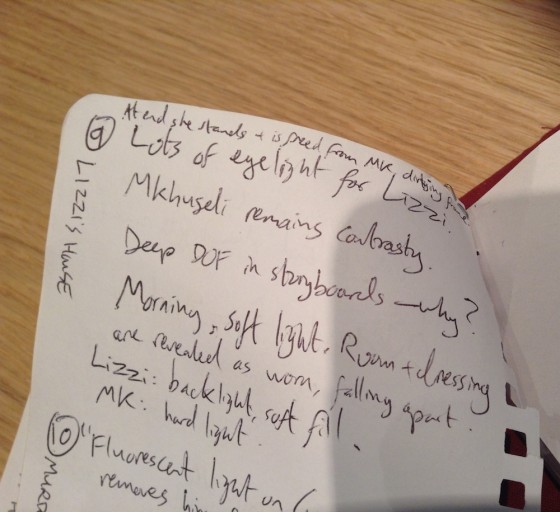

1:48pm As the cast and crew begin to arrive (I’m being accommodated at the location, conveniently) I check my notes for the upcoming scene. These were written during my second reading of the script, a few weeks previously, and include my thoughts and ideas on camerawork and lighting.

1:48pm As the cast and crew begin to arrive (I’m being accommodated at the location, conveniently) I check my notes for the upcoming scene. These were written during my second reading of the script, a few weeks previously, and include my thoughts and ideas on camerawork and lighting.

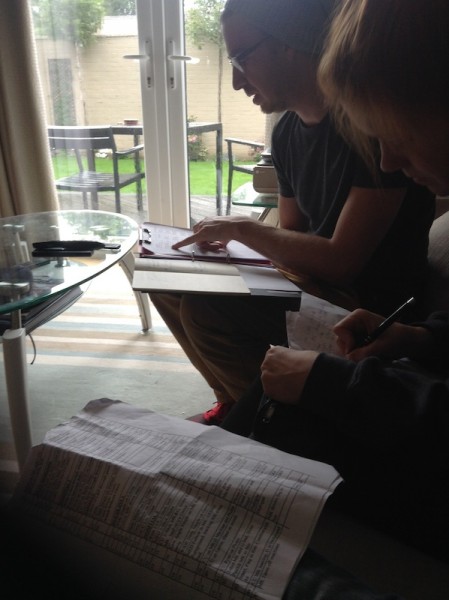

1:54pm I sit down with James the director and Mari the 1st AD to decide what order the day’s set-ups will be shot in. Generally shots are grouped by the rough direction the camera is pointing in, to minimise lighting resets.

1:54pm I sit down with James the director and Mari the 1st AD to decide what order the day’s set-ups will be shot in. Generally shots are grouped by the rough direction the camera is pointing in, to minimise lighting resets.

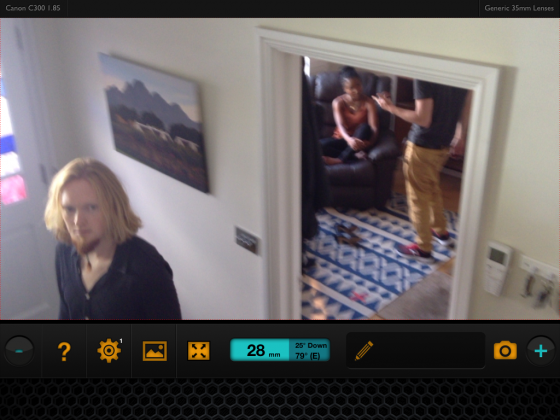

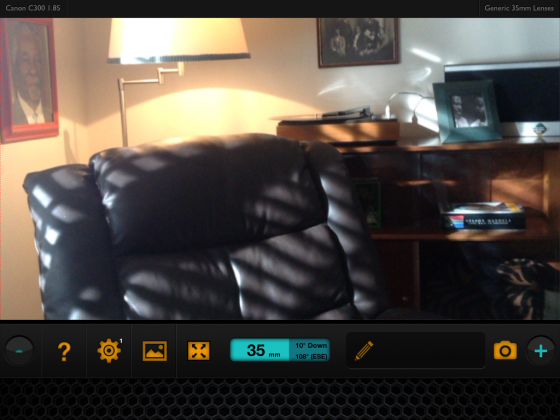

2:13pm Mari assembles the crew to watch a block through of the scene, so everyone knows what they’re doing. Using Artemis, the virtual viewfinder app, James and I select the lens and camera positions for the first set-up. It’s a Steadicam shot, so my 1st AC and Steadicam operator Rupert is in on this conversation.

2:13pm Mari assembles the crew to watch a block through of the scene, so everyone knows what they’re doing. Using Artemis, the virtual viewfinder app, James and I select the lens and camera positions for the first set-up. It’s a Steadicam shot, so my 1st AC and Steadicam operator Rupert is in on this conversation.

2:24pm The cast go into make-up and it’s time for my department to swing into action.

2:24pm The cast go into make-up and it’s time for my department to swing into action.

2:26pm On the recce the previous week I had broadly decided how to light this scene. I confirm the details with Ben, my gaffer, and he and the spark begin setting up the key light outside, a 2.5K HMI, and a kinoflo for fill.

2:26pm On the recce the previous week I had broadly decided how to light this scene. I confirm the details with Ben, my gaffer, and he and the spark begin setting up the key light outside, a 2.5K HMI, and a kinoflo for fill.  2:31pm I go and set up an Arrilite to shine down the stairs.

2:31pm I go and set up an Arrilite to shine down the stairs.

2:31pm The ACs rig the Steadicam and put on my chosen lens.

2:31pm The ACs rig the Steadicam and put on my chosen lens.

2:32pm Meanwhile, DIT and standby 1st AC Max sets up the director’s monitor and focus monitor, which are connected wirelessly to the camera with a Teradek Bolt system.

2:32pm Meanwhile, DIT and standby 1st AC Max sets up the director’s monitor and focus monitor, which are connected wirelessly to the camera with a Teradek Bolt system.

3:09pm Rupert rehearses the Steadicam move using a crew member as a stand-in.

3:09pm Rupert rehearses the Steadicam move using a crew member as a stand-in.

3:13pm 2nd AC Nat marks positions to aid Max in pulling focus.

3:13pm 2nd AC Nat marks positions to aid Max in pulling focus.

3:47pm With camera and lighting set, we get a break waiting for a tricky ageing make-up to be finished. We are completely professional during this hiatus.

3:47pm With camera and lighting set, we get a break waiting for a tricky ageing make-up to be finished. We are completely professional during this hiatus.

4:31pm We frame up the actor, Sibusiso, in position to check how the make-up looks under the right lighting.

4:31pm We frame up the actor, Sibusiso, in position to check how the make-up looks under the right lighting.

4:38pm Dimple, the spark, sits in while Sibusiso returns to make-up for tweaks, and I tweak my lighting.

4:38pm Dimple, the spark, sits in while Sibusiso returns to make-up for tweaks, and I tweak my lighting.

4:41pm I decide that the morning sunlight look I’m going for is too subtle, so I have Ben replace the HMI’s half CTO gel with full CTO.

4:41pm I decide that the morning sunlight look I’m going for is too subtle, so I have Ben replace the HMI’s half CTO gel with full CTO.

4:44pm Rupert and James finesse the camera move. When the make-up artist, Carly, is happy, we start shooting.

4:44pm Rupert and James finesse the camera move. When the make-up artist, Carly, is happy, we start shooting.

4:44pm I sit back and watch the monitor, giving a note or two to Rupert after the first take.

4:44pm I sit back and watch the monitor, giving a note or two to Rupert after the first take.

4:57pm With the Steadicam shot in the can, we select a lens and position for the next shot, a wide.

4:57pm With the Steadicam shot in the can, we select a lens and position for the next shot, a wide.

4:59pm Activity on set pauses while James catches a spider that is freaking out some of the crew.

4:59pm Activity on set pauses while James catches a spider that is freaking out some of the crew.

5:04pm I squeeze myself in behind the camera, which is set up on sticks on the stairs, ready to shoot the wide. James gives some final direction to Lasharne, the actress, before we shoot the first take.

5:04pm I squeeze myself in behind the camera, which is set up on sticks on the stairs, ready to shoot the wide. James gives some final direction to Lasharne, the actress, before we shoot the first take.

5:05pm Nat prepares the clapperboard for the next take.

5:05pm Nat prepares the clapperboard for the next take.

5:12pm The camera team set up the slider for the third set-up.

5:12pm The camera team set up the slider for the third set-up.

5:32pm Carly does final checks on Lasharne’s make-up.

5:32pm Carly does final checks on Lasharne’s make-up.

5:32pm For this set-up I’m using a polyboard under the camera in an effort to raise the room’s ambient light level closer to the burnt-out view through the window.

5:32pm For this set-up I’m using a polyboard under the camera in an effort to raise the room’s ambient light level closer to the burnt-out view through the window.

6:25pm Mari and James adjust an armchair to better suit the next set-up, another slider shot.

6:25pm Mari and James adjust an armchair to better suit the next set-up, another slider shot.

7:12pm Cunningly disguised as a lens, my cup of tea sits in easy reach beside the tripod.

7:12pm Cunningly disguised as a lens, my cup of tea sits in easy reach beside the tripod.

7:12pm We do a camera rehearsal to see if the set-up can accommodate Lasharne standing up, and it can. Max will move the slider while I control pan and tilt, and Rupert pulls focus remotely.

7:12pm We do a camera rehearsal to see if the set-up can accommodate Lasharne standing up, and it can. Max will move the slider while I control pan and tilt, and Rupert pulls focus remotely.

8:13pm As the daylight starts to fade, we complete the scene and break for ‘lunch’. The food is quickly devoured.

8:13pm As the daylight starts to fade, we complete the scene and break for ‘lunch’. The food is quickly devoured.

8:14pm We assemble on set again to watch a block through of the nighttime scene.

8:14pm We assemble on set again to watch a block through of the nighttime scene.

8:21pm Ben discusses a car headlight effect which James wants for the scene.

8:21pm Ben discusses a car headlight effect which James wants for the scene.

8:24pm We clear the set to allow Jorge, the art director, to dress it. I check my notes for the scene.

8:24pm We clear the set to allow Jorge, the art director, to dress it. I check my notes for the scene.

8:29pm Once Jorge has done his thing, James and I pick a lens and position for the first set-up. By this point most of the lighting has been done, except this…

8:29pm Once Jorge has done his thing, James and I pick a lens and position for the first set-up. By this point most of the lighting has been done, except this…

8:50pm Ben and Dimple construct a car headlight rig using two 300W tungsten fresnels mounted on a camera a dolly.

8:50pm Ben and Dimple construct a car headlight rig using two 300W tungsten fresnels mounted on a camera a dolly.

9:10pm The 300s prove too dim and the dolly too flimsy, so instead a Source 4 is rigged to Rupert’s Magliner.

9:10pm The 300s prove too dim and the dolly too flimsy, so instead a Source 4 is rigged to Rupert’s Magliner.

10:29pm The night scene is deliberately designed to echo the day scene, so I’m soon back on the stairs for a wide shot.

10:29pm The night scene is deliberately designed to echo the day scene, so I’m soon back on the stairs for a wide shot.

12:46am We carry on with the scene, getting some very cool shots in the can, before wrapping a little after midnight. The kit is packed away in the living room, ready to load into the van tomorrow. Cider and sleep beckon.

12:46am We carry on with the scene, getting some very cool shots in the can, before wrapping a little after midnight. The kit is packed away in the living room, ready to load into the van tomorrow. Cider and sleep beckon.