Continuing the tenth anniversary releases of the Soul Searcher DVD extras, this week we have the 10 Minute Lighting Masterclass. It’s a quick guide to some of the basic set-ups and techniques used to give the film its cinematic, moody look. Since making this featurette digital cameras have improved vastly and so has my lighting, so these days I would light more subtly with fill and soft sources, but the basic building blocks in this video are still valid. Later in the week I’ll expand on some of those building blocks here on the blog.

Directed by Neil

Blog posts from when Neil used to produce and direct his own micro-budget movies (2001-2014).

Soul Searcher: Low Tech FX

In this 2005 featurette I break down many of the visual effects in my feature film Soul Searcher, revealing how they were created using old school techniques, like pouring milk into a fishtank for apocalyptic clouds. Watch the shots being built up layer by layer, starting with mundane elements like the water from a kitchen tap or drinking straws stuck to a piece of cardboard.

Soul Searcher Bonus Features to be Released

My feature film Soul Searcher started shooting on October 20th 2003. To celebrate the tenth anniversary of the six week shoot, I’ll be releasing one of the DVD extras online every week starting this Sunday with the acclaimed feature-length documentary Going to Hell: The Making of Soul Searcher.

Going to Hell was chosen by Raindance as one of the six best behind-the-scenes docs ever, alongside classics like Heart of Darkness and Lost in La Mancha. Here is the trailer…

In subsequent weeks you can look forward to informative featurettes on lighting, props and martial arts choreography, a breakdown of the sound design of a key scene and a look at how some of the visual effects were created in incredibly low-tech ways using ordinary household items.

Haven’t seen Soul Searcher? Check it out below.

Update: Going to Hell is now online.

What Could Have Been – or Could It?

I recently came across some unpublished blog entries I wrote back in April 2005 when I was trying to sell my feature film Soul Searcher. It’s amazing how close I seemed at the time to getting my big break. It just goes to show you how big a pinch of salt you have to take what sales agents tell you with.

The Secret Diary of Neil Oseman, aged 24¾

April 26th 2005

I’ve decided to start up this secret parallel journal because distributors are now getting interested in the film and from a business point of view it’s not a good idea to be putting too much info about offers and stuff on the website. Hopefully this journal will one day see the light of day.

Today the number of sales agents/distributors planning to make an offer on the film went up to four. Echelon Entertainment (Burbank, sales agents) and Foundation Films (also California, sales agents) joined Third Millennium (London – the only UK distributor interested so far) and CinemaVault Releasing (Toronto, sales agent) in the ranks of the keen. CinemaVault sent me through the official Offer paperwork today but I haven’t read it yet.

The main reason I wanted to write this secret journal is to tell you about the e-mail I just got from Echelon. They reckon there’s a US TV show called Soul Searchers and they want to change my movie’s title to “Grim”. Who the hell’s going to buy a film called Grim? I politely replied that I couldn’t find any mention of this TV series on the net and that it might not be wise to change the film’s title after all the publicity it has had.

Another great story of sales agent stupidity which I couldn’t possibly put on the site is that CinemaVault reckoned SS cost $500,000 USD to make. Hahahahaha! Christ, I’d be seriously worried if SS was the best I could do for half a million bucks. [It actually cost £28,000.]

I just read the CinemaVault contract [see my previous post for an analysis of this]. The list of delivery requirements is five pages long. I estimate producing all the materials to be a two month full-time job. Most ludicrous of all is they want a “cut by cut description of the action in the Picture” and T/C in & outs for EVERY LINE OF DIALOGUE.

April 28th 2005

I just found out that CinemaVault want to push for a theatrical release. Fucking YEAAAH!!!

[An hour or so later…]

Okay, now I’ve calmed down a bit. I’ve recorded my thoughts on video for Going To Hell and I thought I should put some more in writing, only now I don’t know what to write.

Alright, here are the thoughts going round in my head right now:

- This is the FIRST company to make me a formal offer. They’re talking about probably a small US release, but what if another company proposes something bigger?

- SS hasn’t been to any festivals except Borderlines yet. That could be where the big boys pick it up. Surely I shouldn’t sign before it’s had a chance to go to Telluride, Raindance, etc? Though who knows if it’ll get in.

- Cannes of course is coming up. Perhaps I can meet Michael Paszt [from CinemaVault] face to face there. Should I fess up about the budget? (He thinks it cost nearly US$500,000.) After all, the fact that I made it for so little is a major publicity point.

- What will happen when I tell CinemaVault that there’s no 35mm print? Surely they’ve guessed that already, but what if they’re not prepared to bear the cost of it? Can I raise the necessary funds to pay for it, even with a sales agent behind me?

- These are HUGE, HUGE things I’m dealing with. Should I get someone who’s business savvy to negotiate this stuff?

- Who framed Roger Rabbit?

- Doesn’t the fact that I’ve had this offer mean I should be able to get more? I mean, now I can say I’ve been offered a theatrical release – surely other sales agents/distributors will come running? Can I somehow use this to break into Hollywood?

The journal also includes a few previously unpublished thoughts from my trip to Cannes the following month.

I was feeling frustrated that I must seem to buyers like another punk kid with another lame movie. I had to tell them it cost $400,000 to make – if I’d have told them the truth they would either have ripped me off or not given me the time of day. The problem is that it’s not a good advert for me. If SS was the best film I could make for $400,000 I’d be seriously worried. I want to show them the Guardian article – explain how the fact that it was made for so little should be the cornerstone of the publicity campaign – the double-disc DVD, the making-of book. The El Mariachi effect. This is NOT just another low budget film. But I know that just another low budget film was all these people wanted.

Ultimately most of the interest trickled away. After initial enthusiasm and talk of theatrical releases, the sales agents retreated to much smaller offers (“maybe we’ll do a theatrical but probably not”) or stopped returning my calls. Soul Searcher failed to get into any major festivals and was released only on DVD and VOD by a small UK company that went bust shortly before the distribution term expired last year.

The moral of the story is that it can be extremely exciting to be offered a distribution deal, but these companies will have no qualms about leading you on. Most hope you’ll sign quickly, but you should never do that. Ask them tough questions – many won’t even reply and the rest probably won’t give you the answers you want, but you must know what you’re getting into when you sign away your baby.

The One That Got Away: Storyboards

The One That Got Away, the puppet film I submitted to Virgin Media Shorts this year, didn’t have a script. Instead, I storyboarded it from a brief outline written by my wife Katie. Here are those storyboards.

What to Look For in a Distribution Contract

What follows should not be construed as legal advice, and you should ALWAYS get legal advice before signing a contract. However, if you’ve been offered your first distribution deal and money is tight, these basic tips might help you reach a rough understanding of what exactly is on the table before you splash out on a solicitor.

![]() As an example I’m going to use one of the contracts I was offered for my feature Soul Searcher, but not the one I signed.

As an example I’m going to use one of the contracts I was offered for my feature Soul Searcher, but not the one I signed.

Download the contract (PDF, 143KB) – I cannot be held responsible for any losses arising from the use of this contract or the following blog post.

|

Grant of Rights Producer hereby grants to Distributor, with respect to the Term and the Territory set out below, the exclusive distribution and exhibition rights in all media now known or devised later including, but not limited to Theatrical, and Non Theatrical rights, Video/DVD rights, rights pertaining to all forms of Television syndicated or non syndicated, ancillary rights, and all kinds of internet rights pertaining to the feature film entitled “SOUL SEARCHER” (the “Picture”) a film by Neil Oseman, shot in Mini DV. Territory: The World excluding U.K. Term: Commencing immediately and expiring 25 years from the Date of Complete Delivery. |

First of all check out the TERRITORY and MEDIA, i.e. what countries are you allowing the sales agent to distribute the film in and in what form (theatrical, DVD, TV, VOD…), but be aware that just because the contract grants them the right to release your film in cinemas, for example, it doesn’t mean they are under any obligation to do that. Also check out the TERM – how long will they get these rights for? The 25 year term in this contract is unusually long; five would be more typical.

|

Minimum Guarantee (“ Advance”) Distributor agrees to pay Producer Fifteen thousand dollars ($15,000.00 USD) as a Minimum Guarantee of Producer’s share of Gross Receipts payable 20% on signing of this agreement and approval of Chain of title. The remaining 80% balance will be on complete delivery and acceptance, in terms of technical specifications, of all the items noted under Schedule “ A”. |

This contract offers an ADVANCE – meaning that they pay you upfront, later recouping this advance out of the profits. But if your film doesn’t make any profits you’ve still got the advance. This is a great deal for a low budget filmmaker.

|

Distribution Fees, Expenses and Reporting Distributor shall be entitled to a distribution fee of 25% of gross receipts net of withholding tax from exploitation of the Rights. |

The crux of the contract is the PERCENTAGE of any earnings that the sales agent will pass on to you the producer, the higher the better. Here they are proposing to take 25%. That leaves 75% for me – pretty good, huh? But wait….

|

Distributor shall also be entitled to distribution expenses to a maximum cap of U.S. $ 75,000.00 excluding deliverables, unless additional expenses are approved in writing by Producer, which approval will not be unreasonably withheld (“Distribution Expenses”). Distribution Expenses mean out-of-pocket costs incurred by the Distributor, directly or indirectly, in specific connection with distribution, promotion, and marketing of the Picture including any costs which can reasonably and proportionately be allocated to the Picture in accordance with normal accounting practices of the motion picture industry. Gross receipts shall be disbursed in the following order: (1) Distributor’s fee (2) To recoup Distributor’s costs for creating or correcting any deficient materials as set forth above (3) Distribution Expenses (4) Balance to Producer |

Check out that last paragraph. When the money comes in, the sales agent creams off their 25%, then they recoup any costs in correcting the delivery materials (more on that later), then they recoup their EXPENSES, and only then does the producer get what’s left of the pie. So they can swan off to Cannes, Berlin, the American Film Market and so on, to promote their catalogue of films, and take the cost of all their lunches and air fares and slap-up dinners out of the profits before the producers of those films get to see a penny.

You should look for an EXPENSES CAP in the contract, limiting the amount the sales agent can claim out of the profits before they’re passed to you. Here it’s $75,000. The chances of a microbudget film ever making more than that are extremely slim. Result? You never see any money (except the advance, if you’re lucky enough to have been offered one).

|

Representations and Warranties Producer warrants, represents and agrees that it is the holder of the copyright, and has the right to convey all of the rights, licenses and privileges granted herein; that it has not entered and will not enter into any agreement, commitment, arrangement or other grant of rights competing with, interfering with, affecting or diminishing any of the rights and licenses granted herein, and that the Picture, insofar as the Rights granted herein are concerned, are free and clear of any encumbrance and do not infringe upon the rights of any party or parties whomsoever. |

If you sign this contract, what you’re saying via the paragraph above is that you haven’t already sold the rights to anyone else and that your film doesn’t infringe anyone else’s copyright. You’re WARRANTING that you’ve cleared all the music and branding that appears in your film. You got Apple’s permission to show that logo on the iPhone your lead character’s always using, right? And you got WHSmith’s permission to have their shopfront in the background of that highstreet scene?

Now we come to the reason I didn’t sign this contract: the DELIVERY MATERIALS, the list of which occupies five full pages of this contract, so check out the PDF download above to see them.

When you sell a film, you can’t just hand over one master copy of it. The sales agent wants all kinds of different versions – eleven different submasters in this contract, plus all the film elements (those would have been expensive – I didn’t shoot on film!), sound elements, press kits…. And then the documents. Some of the things listed on pages eight and nine (especially the E&O insurance) are serious legal documents that could have cost thousands of pounds to have drawn up. The delivery materials could easily have eaten up the whole $15,000 advance and might even have cost more than the whole production budget of the film. I recommend getting quotes for all delivery materials before signing any distribution deal.

I hope this has given you some idea of what to look for, but let me say again, GET PROFESSIONAL LEGAL ADVICE BEFORE YOU SIGN ANYTHING!

Filming in Belper

Stop/Eject‘s producer Sophie Black gives us a virtual tour of the film’s locations, stopping off along the way to see the work of other filmmakers who have shot in the area. Featuring interviews with actors Georgina Sherrington and Therese Collins, and Yours Truly. Clips courtesy of All Doors Lead Somewhere Productions and Sam Jordan.

Audience Interpretations and the Importance of Test Screenings

One thing I often find myself struggling with as a filmmaker is clarity of motivation and storyline. It’s amazing how easily an audience can misinterpret something – or perhaps I should say how easily they can interpret it differently from the director, writer, etc. Here are some examples:

- Stop/Eject‘s protagonist Kate is a costume designer, though this is never stated explicitly, and the scene that might have hinted most at it was deleted early on in the editing process. In the opening scene she enters a charity shop and gets a scrapbook of costume designs out of her bag to refer to whilst browsing the clothing rack. But after trimming the scene to improve the pace, the sequence of events in the locked edit became: Kate enters the charity shop with her husband Dan; she approaches a clothing rack and opens her bag; we then cut to Dan asking the shopkeeper how much a record is, drawing her away from Kate’s location. In short, it looked like Kate was opening her bag to do some shoplifting and Dan was abetting her by distracting the shopkeeper. I was blind to this because I knew Kate’s real intention, but my wife picked it up as soon as she saw it. Despite having locked the edit, on spotting this issue we hastily cut out the shot of Kate opening her bag.

- In the same scene in Stop/Eject, Alice the shopkeeper was filmed looking at her watch. The intention was to show that she knew the cassette in the magic tape recorder needed turning over very soon, and was weighing up whether she had time to answer Dan’s query first. But test audiences thought that, given Alice’s mysterious connection to the time-travelling tape recorder, she was looking at her watch because she knew that any minute now an accident was going to happen, which indeed it does at the end of the scene. The solution was to simply cut Alice’s watch check.

- My 2012 Virgin Media Shorts entry, Ghost-trainspotting, is about a deceased nerd who spots trains of an equally ghostly nature. His ghostly nature, however, is not revealed until late in the film. This revelation comes in the form of (a) him ascending into the clouds in a shaft of heavenly light, his final mission on earth being complete, and (b) a closing shot of his photo in a shrine. But we had to cut the shrine shot due to the competition’s strict length limit, and some viewers thought the shaft of heavenly light looked more like he was being beamed up by aliens. Result? A complete misunderstanding of the story. Sadly, with the competition deadline upon me, I was unable to correct this issue in time.

Audiences aren’t stupid; you just have to remember that they haven’t read the script, been on the set and worked on the edit for months. They’re coming to it completely fresh, and if the right clues aren’t in the film, they have little chance of interpreting it as you intended.

This is why test screenings are so important. Happily most of these types of issues can be resolved fairly easily by cutting something out or adding a line of ADR, but unless you show your edit to fresh eyes you probably won’t even know they are issues in the first place.

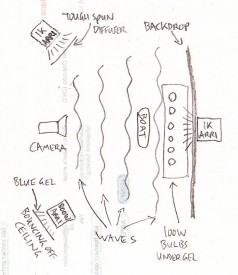

Lighting The One That Got Away

Here’s a breakdown of the lighting choices made on my little puppet film, The One That Got Away. You can watch the film over at the Virgin Media Shorts website. If you enjoy it, please use the tweet button to register your vote and help us get a place on the shortlist.

Conventional wisdom with marionettes is probably to go for very flat lighting with no backlight, to make it as difficult as possible to see the strings. But on TOTGA I wanted to embrace and celebrate the tactile, handmade look of the puppets and sets, so I chose a traditional three-point lighting scheme that imparted depth and made no effort to hide the strings.

Normally I shoot wide open – typically f1.8 – on my DSLR, but as the puppets were small the depth of field would have been ridiculously shallow at that aperture. Instead I lit the set very brightly (about 3KW of tungsten horsepower in our cramped living room – not very pleasant during a heatwave!) and stopped down to around f4.

Daylight

For the daylight scenes I used my three open-face tungsten Arrilites: a 1K poking over the top of the backdrop for backlight, another 1K with tough-spun diffuser off camera left for key, and an 800W bouncing off the ceiling for fill. This last lamp was gelled blue to suggest ambient skylight.

I tried to simulate the camerawork that would have been used had this been shot at sea with real actors, so:

- the camera bobs up and down in wide shots, as if Henry’s boat is being shot from another vessel;

- the camera and boat are fixed in close-ups, with the background bobbing up and down, as if we’re now shooting on a tripod in Henry’s boat.

Underwater

The underwater dream sequence was all shot dry-for-wet at 50fps for a watery slow motion. Using Magic Lantern I dialled in a cool white balance of around 2500K, and pumped in smoke to add diffusion and suggest currents. (I wished I’d use a lot more smoke, but we would have all choked to death.)

I used just two light sources: the 1K backlight, now gelled blue, and the other 1K, bounced off sheets of silver wrapping paper tacked loosely to the ceiling. This is exactly the same method I used for a scene in Ashes – flapping a piece of card at the wrapping paper makes the light ripple in a very watery way.

The underwater lighting scheme was a lot darker than the daylight one, so I opened up to around f2, giving a crazily shallow depth of field that worked nicely for this dream sequence. The mermaid’s close-ups were all shot through a CD case for an old-school soft-focus look.

I would have liked to have shot this sequence handheld, but a lack of crew meant I had to lock the camera off so I could operate the smoke machine, fan the wrapping paper and move little fish through frame.

Sunset

When Henry awakens from his dream, the fish escapes and he gives chase. Orange gels and lens flare were used to suggest the sun getting lower in the sky, until finally Henry and his quarry are silhouetted against the solar disc itself. This is a domestic 100W tungsten bulb peeking over the back wave. The only other light source is a row of six more such bulbs under a sheet of orange gel, just behind and below the first one.

As the scene moves into twilight, the first bulb is removed and the orange gel over the other six is replaced with a purple one. The 1K backlight is turned back on (possibly it would have been more realistic without, but I’m just a sucker for backlight) and some pink fill is provided by placing a sheet of Minus Green gel on the other 1K and bouncing it off a reflector.

That’s all folks. Please do tweet about the film (being sure to include the title The One That Got Away and the hashtag #VMShortsVote for it to count as a vote) and click here to watch the behind-the-scenes featurette if you missed it.

The Making of Henry

Guest blogger Katie Lake tells the story of how Henry Otto, the marionette star of The One That Got Away, came into this world. Click here to watch the film and please tweet about it to help us make the competition shortlist.

It started as a whim, a crazy idea. I have wanted to do a puppet film with Neil for a while. But if I couldn’t make a puppet, there would be no puppet film. No pressure.

I started with his head. I wound newspaper around metal wire that would become his controls, then covered the newspaper ball with a layer of air-drying clay, shaping his head, and face. I did a test with lights to see if I liked the shape I got (1).

I then made his body. This started out as a toilet roll tube, covered in papier-mâché, and his arms and legs were rolled up newspaper “beads”. I then painted them beige, and sculpted hands using more clay over wire. I fit the legs and arms with wire, and before I put him together this was how he was looking (2). I liked the big head, spindly legs and long arms. So together he went.

I made the start of a neck, and then painted his face. He now had an expression, a look, a character. I (hesitantly) fell in love with Henry when I first sculpted his head and face, but was really worried that I wouldn’t be able to do him justice with paint. Thankfully I was pleased with the results. And this is when I knew the name swirling around in my head, was the name he was going to be. There is something about him that reminds me of my maternal grandfather’s side of the family, so Henry is sort of an homage.

He then needed some clothes. Despite, or maybe because of my costume background, deciding what clothes to make for him was by far the hardest bit. In the end we decided jeans were a good place to start. I drafted a pattern in cloth, then altered it, and cut them out of an old charity shop skirt. I also gave him some hand stitched details around the waist. I temporarily strung him up, and tested out what we could get him to do. This was also his first camera test (3).

It was now that we realised he needed lateral head controls (one on either side of his head so we could make him look left and right). Oops. I attached lateral controls to the outside of his head as I didn’t want to risk drilling, so he now needed a hat or wisps of hair to hide the wire. He also needed a top, and boots.

Enter Jo Henshaw, who kindly offered to come and help out. She helped finalize costume design decisions, and made him his cute beanie (out of an old sleeve) and started his sweater (out of an old sweater) (4).

I made boots (out of more toilet roll tubes cut and bent, glued into shape and then papier-mâchéd, and then painted black) (5). I should also mention stop-motion animator Emily Currie, another helpful volunteer, who used her expertise to ensure the lateral controls stayed put.

Henry’s sweater was then sewn onto him, covering the multiple pieces. I kept the arms separate for greater movement. I finished him off with braces made out of old shoe laces, made buttons out of clay which I painted brown, sewed a patch onto his arm from an old scrap and aged his costume with some brown and black paint.

Lastly I strung him up using extra strong navy thread. The T bar I made using a piece of flat doweling, some screw eyes (upcycled from old curtain rings) and nails to make the cross bars removable. And Henry was ready for his debut (6).

You can visit Katie’s blog at www.katiedidonline.com. To find out what Henry’s up to, why not befriend him on Facebook?

Tomorrow I’ll look at the camera and lighting techniques used to shoot the film.