An article of mine from 2014 weighing the merits of shooting at 24 vs. 25 frames per second has recently been getting a lot of hits. I’m surprised that there’s still so much uncertainty around this issue, because for me it’s pretty clear-cut these days.

When I started out making films at the turn of the millennium, 25fps (or its interlaced variant, 50i) was the only option for video. The tapes ran at that speed and that was that. Cathode ray tube TVs were similarly inflexible, as was PAL DVD when it emerged.

Film could be shot at 24fps, and generally was for theatrical movies, since most cinema projectors only run at that speed, but film for television was shot at 25fps.

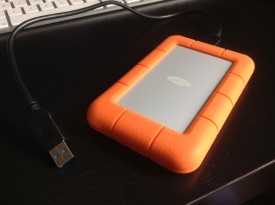

Three big technological shifts occurred in the late noughties: the delivery of video over the internet, flat-screen TVs and tapeless cameras. All of these support multiple frame rates, so gradually we found that we had a choice. At the start of a shoot, as a DP I would have to ask which frame rate to set.

Americans and others in NTSC regions are in a different situation. Their TV standard of 30fps has a discernibly different look to the international movie standard of 24fps, so the choice of frame rate is as much creative as it is technical. I don’t think anyone can tell the difference between 24 and 25fps, even on a subconscious level, so in Europe it seems we must decide on a purely technical basis.

But in fact, the decision is as much about what people are used to as anything else. I shot a feature film pilot once on 35mm at 25fps and it really freaked out the lab simply because they weren’t used to it.

And what people seem to be most used to and comfortable with in the UK today is 24fps. It offers the most compatibility with digital cinemas and Blu-ray without needing frame rate conversion. (Some cinemas can play 25fps DCPs, and Blu-rays support 25fps in a 50i wrapper which might not play in a lot of US machines, but 24 is always a safer bet for these formats.)

Historically, flickering of non-incandescent light sources and any TV screens in shot was a problem when shooting 24fps in the UK. These days it’s very easy to set your shutter to 172.8° (if your camera measures it as an angle) or 1/50th (if your camera measures it as an interval). This ensures that every frame – even though there are 24 of them per second – captures 1/50th of a second, in sync with the 50Hz mains supply.

The Times when 25fps is best

There are some situations in which 25fps is still the best or only option though, most notably when you’re shooting something intended primarily for broadcast on a traditional TV channel in the UK or Europe. The same goes if your primary distribution is on PAL DVD, which I know is still the case for certain types of corporate and educational videos.

Once I was puzzled by a director’s monitor not working on a short film shoot, and discovered that it didn’t support 24fps signals, so I had to choose 25 as my frame rate for that film. So it might be worth checking your monitors if you haven’t shot 24fps with them before.

Finally, if your film contains a lot of archive material or stock footage at 25fps, it makes sense to match that frame rate.

Whichever frame rate you ultimately choose, always discuss it with your postproduction team ahead of time to make sure that you’re all on the same page.