If you’ve done much still photography, particularly on celluloid, you will probably have heard of the Sunny 16 Rule. It’s a useful shortcut for correctly exposing bright day exteriors without needing a light meter. Is it of any use in digital cinematography though? Yes, and I’ll explain how.

How the rule Works

Sunny 16 is very simple: if the sun is out, set your aperture to f/16 and your shutter speed denominator to the same as your ISO. For example, at ISO 100 set the shutter to 1/100th of a second. At ISO 400 set the shutter to 1/400th of a second – or 1/500th of a second, if that’s the closest option the camera permits – and so on.

You can use the rule to work out other combinations from there. Say your ISO is 100 but you want the sharper, less motion-blurred look of a 1/400th shutter. That’s two stops slower, so open the aperture from f/16 to f/8. (Check out my exposure series if this is all Dutch to you.)

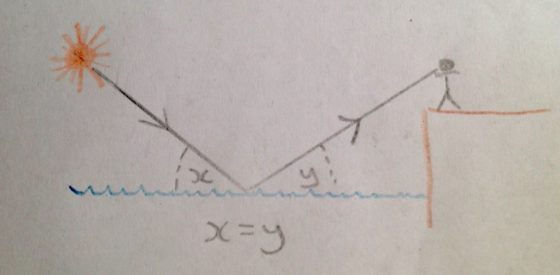

The Sunny 16 Rule works because the sun outputs a constant amount of light and is a constant distance from the earth – at least constant enough to make no significant difference. The sun’s illuminance at the earth’s surface is about 10,000 foot-candles. The following formula relates illuminance (b) to f-stop (f), shutter speed (s) and ISO (i):

Using Sunny 16 in the case of ISO 100 and a shutter speed of 1/100th of a second, this formula gives us…

… 6,400 foot-candles. Less than 10,000fc, certainly, but remember this is only a rule of thumb – and one designed for film, which isn’t hurt at all by a little over-exposure. The rule probably accounts for the fact that you may want to see into the shadows a bit too. (See my article “How Big a Light Do I Need?” for explanations of illuminance and foot-candles and more on the above formula.)

Anyway, you can see from the equation why the shutter speed denominator and ISO cancel each other out if they’re the same.

Using the rule in cinematography

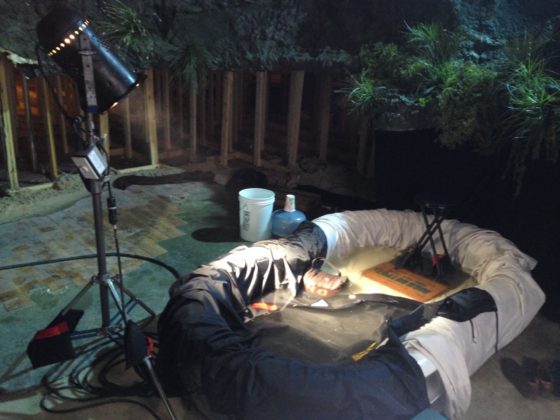

A few weeks ago when I was on the banks of the River Cam setting up for a scene in Harvey Greenfield is Running Late, my 1st AC Hamish Nichols asked which ND filter I wanted in the matte box. It was 5:30am; the sun had barely risen and certainly wasn’t high enough yet to reach me and my light meter over the trees and buildings on the horizon. But I knew that it would be hitting us by the time we turned over, and that the weather forecast was for a completely cloudless day, indeed the hottest day of the year at that time. So I was able to predict that we’d need the 2.1 ND.

A few weeks ago when I was on the banks of the River Cam setting up for a scene in Harvey Greenfield is Running Late, my 1st AC Hamish Nichols asked which ND filter I wanted in the matte box. It was 5:30am; the sun had barely risen and certainly wasn’t high enough yet to reach me and my light meter over the trees and buildings on the horizon. But I knew that it would be hitting us by the time we turned over, and that the weather forecast was for a completely cloudless day, indeed the hottest day of the year at that time. So I was able to predict that we’d need the 2.1 ND.

How did I work this out? From the Sunny 16 Rule as follows:

- I was shooting with a 1/50th of a second shutter interval (a 172.8° shutter angle at 24fps), so the Rule told me that f/16 (or T16) at ISO 50 would be the right exposure.

- I was actually at ISO 800, which is four stops faster than ISO 50. (Doubling 50 four times gives you 800.)

- I wanted to shoot at T5.6, which is three stops faster than T16.

- That’s a total of seven stops too much light. To find the right optical density of ND filter you multiply that by 0.3, so 0.3 x 7 = 2.1. (More on this in my ND filters post.)

Everything on a film set sucks up time, so the more you know in advance, the more efficient you can be. Little tricks like this mean you don’t have to do a last-minute filter swing and waste five minutes that the director could have used for another take.