Astera Titan Tubes seem to be everywhere at the moment, every gaffer and DP’s favourite tool. Resembling fluorescent tubes, Asteras are wireless, flicker-free LED batons comprised of 16 pixels which can be individually coloured, flashed and programmed from an app to produce a range of effects.

Astera Titan Tubes seem to be everywhere at the moment, every gaffer and DP’s favourite tool. Resembling fluorescent tubes, Asteras are wireless, flicker-free LED batons comprised of 16 pixels which can be individually coloured, flashed and programmed from an app to produce a range of effects.

Here are five ways in which I used Titan Tubes on my most recent feature, Hamlet. I’m not being sponsored by Astera to write this. I just know that loads of people out there are using them and I thought it would be interesting to share my own experiences.

1. Substitute fluorescents

We had a lot of scenes with pre-existing practical fluorescents in them. Sometimes we gelled these with ND or a colour to get the look we wanted, but other times it was easier to remove the fluorescent tube and cable-tie an Astera into the housing. As long as the camera didn’t get too close you were never going to see the ties, and the light could now be altered with the tap of an app.

On other occasions, when we moved in for close-ups, the real fluorescents weren’t in an ideal position, so we would supplement or replace them with an Astera on a stand and match the colour.

2. Hidden behind corners

Orientated vertically, Asteras are easy to hide behind pillars and doorways. One of the rooms we shot in had quite a dark doorway into a narrow corridor. There was just enough space to put in a vertical pole-cat with a tube on it which would light up characters standing in the doorway without it being seen by the camera.

3. Eye light

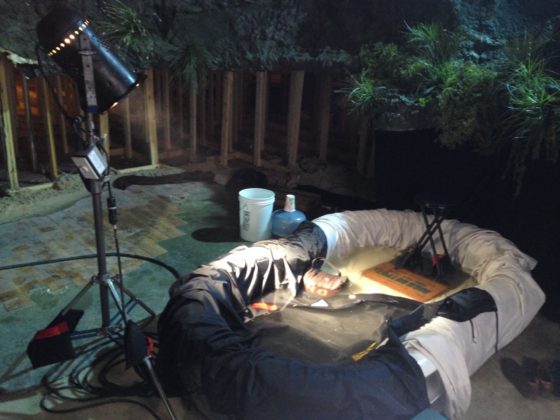

Ben Millar, Hamlet‘s gaffer, frequently lay an Astera on the floor to simulate a bit of floor bounce and put a sparkle in the talent’s eye. On other occasions when our key light was coming in at a very sidey angle, we would put an Astera in a more frontal position, to ping the eyes again and to wrap the side light very slightly.

4. rigged to the ceiling

We had a scene in a bathroom that was all white tiles. It looked very flat with the extant overhead light on. Our solution was to put up a couple of pole-cats, at the tops of the two walls that the camera would be facing most, and hang Asteras horizontally from them. Being tubes they have a low profile so it wasn’t hard to keep them out of the top of frame. We put honeycombs on them and the result was that we always had soft, wrappy backlight with minimal illumination of the bright white tiles.

5. Special effects

One of the most powerful things about Titan Tubes is that you can programme them with your own special effects. When we needed a Northern Lights effect, best boy Connor Adams researched the phenomenon and programmed a pattern of shifting greens into two tubes rigged above the set.

On War of the Worlds in 2019 we used the Asteras’ emergency lights preset to pick up some close-ups which were meant to have a police car just out of shot.

There are all kinds of other effects you could use the tubes for. There is a good example by DP Rowan Biddiscombe in this article I wrote for British Cinematographer.