Filmmakers have used all kinds of tricks over the years to show low or zero gravity on screen, from wire work to underwater shooting, and more recently even blasting off to capture the real thing.

Many early sci-fi films simply ignored the realities of being in space. The 1964 adaptation of H. G. Wells’ The First Men in the Moon, for example, shows its Victorian astronauts walking around the “lunar” surface without any attempt to disguise the earthly gravity.

But as the space race heated up, and audiences were treated to real footage of astronauts in Earth orbit, greater realism was required from filmmakers. None met this challenge more determinedly than Stanley Kubrick, who built a huge rotating set for 2001: A Space Odyssey. The set was based on a real concept of artificial gravity: spinning the spacecraft to create centrifugal force that pushes astronauts out to the circular wall, which effectively becomes the floor. Kubrick’s giant hamster wheel allowed him to film Dr Dave Bowman (Keir Dullea) running around this circular wall.

Ron Howard chose to shoot in real weightlessness for his 1995 film Apollo 13, a dramatisation of the near-disastrous moon mission that saw astronauts Jim Lovell, Jack Swigert and Fred Haise temporarily stranded in space after an explosion in an oxygen tank. Howard and his team – including actors Tom Hanks, Kevin Bacon and Bill Paxton – took numerous flights in the KC-135 “vomit comet”. This NASA training plane flies in a steep parabola so that passengers can experience 25 seconds of weightlessness on the way down.

612 parabolas were required for Howard to capture the pieces of the action he needed. Apparently few people lost their lunch, though minor bumps and bruises were sometimes sustained when weightlessness ended. “It was difficult to do,” said the director at the time, “but it was an extraordinary experience.” The vomit comet footage was intercut with lower-tech angles where the actors were simply standing on see-saw-like boards which grips could gently rock up and down.

For a 2006 episode of Doctor Who, “The Impossible Planet”, the production team used Pinewood Studios’ underwater stage for a brief zero-gravity sequence. MyAnna Buring’s character Scooti has been sucked out of an airlock by a possessed colleague, and the Doctor and co watch helplessly through a window as her body floats towards a black hole. Buring was filmed floating underwater, which enabled her long hair to flow out realistically, and then composited into CGI of the black hole by The Mill.

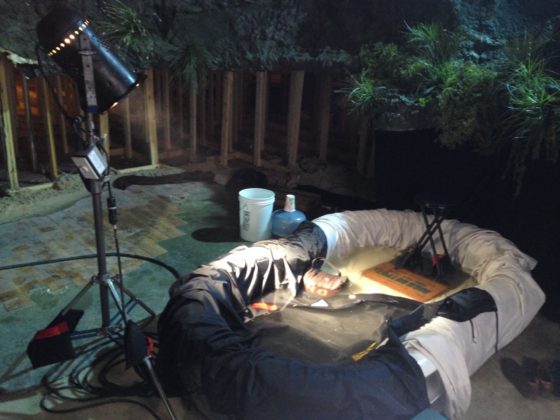

On the whole though, wire work is the standard way of portraying zero gravity, and a particularly impressive example appeared in 2010’s Inception. Director Christopher Nolan was inspired by 2001’s weightless scenes, for which Kubrick often pointed the camera straight upwards so that the suspending wires were blocked from view by the actor’s own body.

Inception sees a fight in a dreamscape – represented by a hotel corridor – becoming weightless when the dreamers go into free-fall in the real world. The scene was shot with a 100 ft corridor set suspended on end, with the camera at the bottom shooting upwards and the cast hung on wires inside. (Miniature explosions of spacecraft traditionally used a similar technique – shooting upwards and allowing the debris to fall towards the camera in slow motion.)

2013’s Gravity filmed George Clooney and Sandra Bullock in harnesses attached to motion-control rigs. Footage of their heads was then composited onto digital body doubles which could perfectly obey the laws of zero-gravity physics.

But all of these techniques were eclipsed last year by Vyzov (“The Challenge”), a Russian feature film that actually shot aboard the International Space Station. Director Klim Shipenko and actor Yulia Peresild blasted off in a Soyuz spacecraft piloted by cosmonaut Anton Shkaplerov in autumn 2021. After a glitch in the automatic docking system which forced Shkaplerov to bring the capsule in manually, the team docked at the ISS and began 12 days of photography. Another glitch temporarily halted shooting when the station tilted unexpectedly, but the filmmakers wrapped on schedule and returned safely to Earth.

At the time of writing Vyzov has yet to be released, but according to IMDb it “follows a female surgeon who has to perform an operation on a cosmonaut too ill to return to Earth immediately”. The ISS footage is expected to form about 35 minutes of the film’s final cut.

While Vyzov is not the first film to be shot in space, it is the first to put professional cast and crew in space, rather than relying on astronauts or space tourists behind and in front of camera. It certainly won’t be the last, as NASA announced in 2020 that Tom Cruise and SpaceX would collaborate on a $200 million feature directed by Doug Liman (Edge of Tomorrow, Jumper) again to be shot partly aboard the ISS. It’s possible that Vyzov was rushed into production simply to beat Hollywood to it. While realistic weightlessness is a definite benefit of shooting in space for real, the huge amount of free publicity is probably more of a deciding factor.