In the autumn of 2014 I served as director of photography on Ren: The Girl with the Mark, an incredibly ambitious short-form fantasy series, and have since been assisting with postproduction in various ways. Now that season one of the show is complete and ready to show to the public at last, I took the opportunity to sit down with director Kate Madison and ask her about some of the unique aspects of the show’s production…

Kate, many people will know you as the director, producer, co-writer, actor and general driving force behind Born of Hope, a Lord of the Rings fan film with over 35 million YouTube views. Did that film’s success open any doors for you, and what was the journey from there that led you to want to make a web series?

Born of Hope potentially opened doors even if they weren’t visible doors, in the sense that although it didn’t result in Hollywood coming calling, it created a a bit of a buzz and it became known in the industry. Myself and Christopher Dane [the lead actor] did start work on a fantasy feature film script called The Last Beacon and spent time trying to pursue that avenue. That then led into another feature film idea, so we were looking down the route of a feature film rather than anything else, and spent what felt like a number of years just not going anywhere.

I started thinking, what can we actually do when we don’t know investors or people with money. We concluded that with the internet – there’s an audience there, our audience is there. The crowdfunding thing which worked for Born of Hope is online, so we need to go back to that.

Many people will ask, “Why fantasy when there are so many cheaper and easier genres?” How do you respond to that?

For me, film and TV is about escapism, so I enjoy action-adventures and comedies and historical stuff – things that are not Eastenders. Fantasy is a huge genre. To me it’s a way to have the freedom to do whatever you want. I can take things I like – historical things, costumes, set design – and the joy of fantasy over period is, you can go, “I’m going to use this Viking purse with this medieval-looking helmet!” I like the freedom of fantasy. You can still have a character-driven, interesting story, set in somewhere fantastical, or even just a forest. There’s no dragons or creatures in Ren – so far – but the options are there, that’s the joy of it.

There was an enormous amount of goodwill and legions of volunteers who helped with Born of Hope. How important were those people, and finding others like them, when it came to making Ren?

Hugely important! Born of Hope could not have been made without a ton of volunteers, having no budget at all. With Ren, because we were in a similar position – which was a shame really, after all that time we still hadn’t got a big enough budget – we again had to rely on volunteers to make it possible!

There was an incredible sense of community, of shared ownership and very high morale throughout the production of Ren. Was it important to you to foster those things?

It’s incredibly important to keep morale high. I think it’s slightly easier when people are volunteering because they’re there because they want to be there and not just for the pay cheque. I was very keen to let everyone have fun on the project and also to have fun myself, because these projects are incredibly hard. So if the work was all done for the day, OK, I’m allowed to switch off now and grab a Nerf gun! People were staying there [at the studio], so they wanted to have a good time in the evening.

If we work a little later because there’s a break in the middle where we’re having a laugh, that means you can go later because everyone’s chilled rather than slogging away and not feeling like they’re enjoying themselves.

When people are volunteering, it feels like [the project] is everybody’s, and it is. People would come in and help and maybe end up designing a dress. The joy of filmmaking for me is the collaborative nature of it. There’s always someone behind you with an idea. You don’t feel like you’re ever on your own completely. If you’re at a loss, then someone else – whether it’s the DoP or the runner – [can suggest things].

Very few micro-budget productions have their own studio, but Ren took over a disused factory for several months. How did that come about, and what were the benefits of it?

The benefits were through the roof, I’d say! We wonder if the project would have happened without it.

As we were going through budgets and scouting locations, we realised how difficult it was going to be [to shoot on location] – the logistics of making the village look like the village in the script and what if it rained for that week [the location was booked for]? It was just terrifying.

We started to think, is there another option here? It was just luck that Michelle [Golder, co-producer], on a dog walk, got talking to someone who knew someone. He mentioned this place in Caxton which was really big but we wouldn’t be in anyone’s way and we could just take it over. We were going to get a really good deal because it was sitting empty. It was twice as much for six months in Caxton in comparison with six days on location. And we would have the freedom to build whatever we wanted! There was all this interior space we could build in but also have costume rooms and production offices.

I’ve always loved the idea of having a place to work where everyone can come together. It’s fantastic nowadays that you can communicate with people all over the world, but you can’t beat a face-to-face conversation with someone and being able to look at the same picture and point at it and talk about it. It meant we were able to achieve a lot more in scope but also in quality.

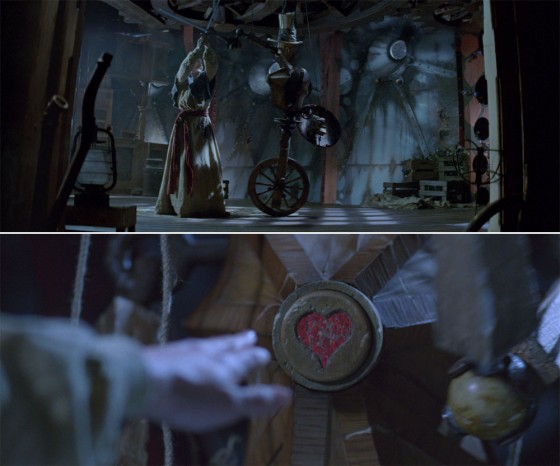

Perhaps the greatest achievement of the production was creating a medieval village from scratch. Building the set, sourcing enough extras and costuming everybody were three massive challenges. How did you tackle those?

I live in Cloud Cuckoo land sometimes I guess! The set build, I thought, “It’s fine, we can do this, we can build this circular wall essentially with a few alleyways going off it and fill it with some market stalls.” Chris was in charge of building the set, and did an amazing job with a bunch of volunteers that came back over and over again. Although we bought a bunch of materials we made use of an amazing site called Set Exchange which is a sort of Freecycle for sets and we found a bunch of flats on there – that helped a lot.

Populating the village was always going to be challenging. Suzanne [Emerson] who also played the role of Ida got heavily involved in helping to find extras. She’s involved in a lot of the amateur dramatics in Cambridge. It was probably horrible [for Suzanne and Michelle] but an amazing miracle for us that we’d finish shooting one day and go, “You know we’re actually going to shoot that tomorrow and we need some people,” and then the next morning you’d turn up and people would show up to do it. We had varying numbers, but there was never a day when no-one showed up.

As for dressing them – we grabbed all of the Born of Hope costumes, Miriam [Spring Davies, costume designer] had a bunch of stock stuff as well. We ended up buying a bunch of things from New Zealand, from a costume house called Shed 11 that did Legend of the Seeker. The Kah’Nath armour came from Norton Armouries; John Peck – who had been involved with Born of Hope supplying stuff for orcs – I called on his good will again.

It was lovely to make the hero costumes from scratch. Miriam and I would go through the costume designs and then we went and looked at material. Chris and I randomly on a holiday to Denmark found some material we really liked for Karn’s tunic. Ren’s dress – I bought that material ages ago and it had been sitting around. Miriam and I took a trip to the re-enactors’ market as well. And we went to Lyon’s Leathers, spent what felt like a whole day wandering his amazing storeroom and picking out stuff for different characters, for Hunter’s waistcoat and Ren’s overdress, and we got the belts made there.

I’ve heard you say more than once, “If it’s not right, it’s not worth doing.” How important is quality to you, and how do you balance that with the budgetary and scheduling pressures of such a huge project?

I’m not very good at compromising. If we’re going to spend months and months working on something that none of us are going to be happy with or proud of then it’s a waste of time and we might as well stop now. I think it’s probably that I’d like to be off in New Zealand making Legend of the Seeker, so I treat it as if I’m doing that I suppose, and I try not to let the budget or circumstances stop us from doing that.

I knew that most of the things are achievable. You know, to put together a costume that’s weathered well and looks really interesting is not hard to do, it just takes more time to do than buying it off the shelf and sticking it on, but the quality difference is so extreme. People will be much happier with you in the end if you’ve worked them hard for an amazing outcome than if you’ve worked them hard and it looks rubbish.

Most filmmakers are making stand-alone shorts or features, though the medium of web series is growing. Do you think it’s the way forward? Do you think there can be a sustainable career in it?

Ren is going to be an interesting experiment – can people watch something that, if we stuck [all the 10-minute episodes] together would be a pilot for TV – will they watch that on the web in the same way they would watch a TV thing or will they get bored and go and watch cats?

It is a new field. Although web series have been going on a long time, it’s still growing, there’s no funding in the UK, there’s no obvious way of having revenue from it, because the online platforms like YouTube, the advertising revenue is absolutely minimal as a percentage of views, and there’s only so many t-shirts you can sell. We struggled to raise money for the first season and we only raised enough to barely scrape our way through while putting in our own money.

Unless it does amazingly and maybe garners the interest of a big brand or sponsorship, if we’re having to crowdfund every time and we can’t crowdfund the huge figures that we’d need to make this, then it might not be the way forward for Ren and we might need to figure out a different thing… [unless] we get picked up by a bigger corporation like Amazon or Netflix.

We’ll see how this first season goes. We’d love it to become sustainable and a show that we can keep putting out and people can enjoy, but this is the experiment for that I suppose.

You can watch Ren: The Girl with the Mark for free, Tuesdays at 8pm GMT from March 1st, at rentheseries.com or on the Mythica Entertainment channel on YouTube.