The main event of last week’s prep was a test at Panavision of the Arri Alexa XT, Red Gemini and Sony F55, along with Cooke Panchro, Cooke Varotal, Zeiss Superspeed and Angenieux glass. More on that below, along with footage.

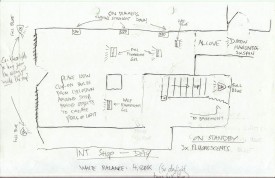

The week started with Zoom meetings with the costume designer, the make-up artist, potential fight choeographers and a theatrical lighting designer. The latter is handling a number of scenes which take place on a stage, which is a new and exciting collaboration for me. I met with her at the location the next day, along with the gaffer and best boy. After discussing the stage scenes and what extra sources we might need – even as some of them were starting to be rigged – I left the lighting designer to it. The rest of us then toured the various rooms of the location, with the best boy making notes and lighting plans on his tablet as the gaffer and I discussed them. They also took measurements and worked out what distro they would need, delivering a lighting kit list to production the next day.

Meanwhile, at the request of the producer, I began a shot list, beginning with two logistically complex scenes. Despite all the recces so far, I’ve not thought about shots as much as you might think, except where they are specified in the script or where they jumped out at me when viewing the location. I expect that much of the shot planning will be done during the rehearsals, using Artemis Pro. That’s much better and easier than sitting at home trying to imagine things, but it’s useful for other departments to be able to see a shot list as early as possible.

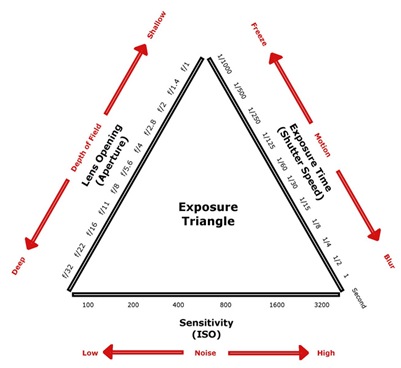

So, the camera tests. I knew all along that I wanted to test multiple cameras and lenses to find the right ones for this project, a practice that is common on features but which, for one reason and another, I’ve never had a proper chance to do before. So I was very excited to spend Wednesday at Panavision, not far from my old stomping ground in Perivale, playing around with expensive equipment.

Specifically we had: an Arri Alexa – a camera I’m very familiar with, and my gut instinct for shooting this project on; a Sony F55 – which I was curious to test because it was used to shoot the beautiful Outlander series; and a Red Gemini – because I haven’t used a Red in years and I wanted to check I wasn’t missing out on something awesome.

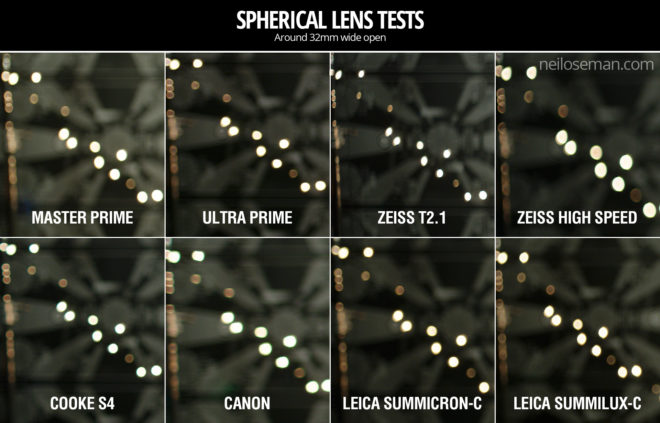

For lenses we had: a set of Cooke Panchros – again a gut instinct (I’ve never used them, but from what I’ve read they seemed to fit); a set of Zeiss Superspeeds – selected after reviewing my 2017 test footage from Arri Rental; a couple of Cooke Varotal zooms, and the equivalents by the ever-reliable Angenieux. Other than the Angenieux we used on the B-camera for The Little Mermaid (which I don’t think we ever zoomed during a take), I’ve not used cinema zooms before, but I want the old-fashioned look for this project.

Here are the edited highlights from the tests…

You’ll notice that the Sony F55 disappears from the video quite early on. This is because, although I quite liked the camera on the day, as soon as I looked at the images side by side I could see that the Sony was significantly softer than the other two.

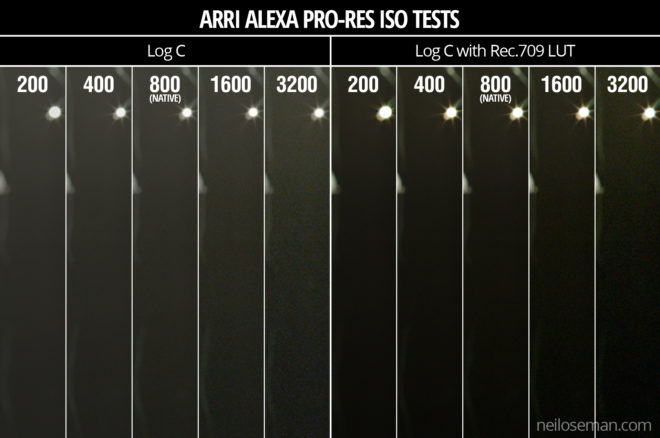

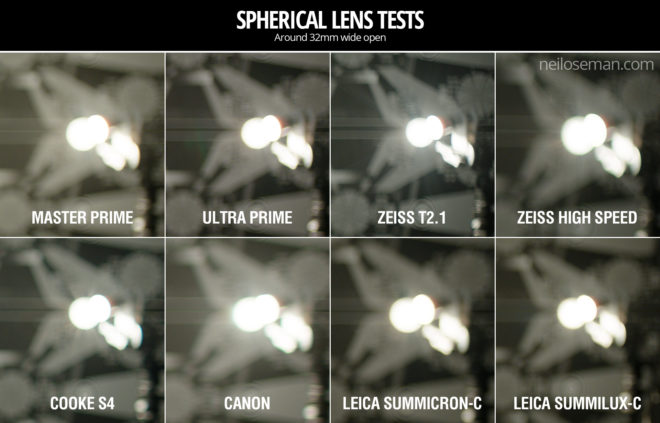

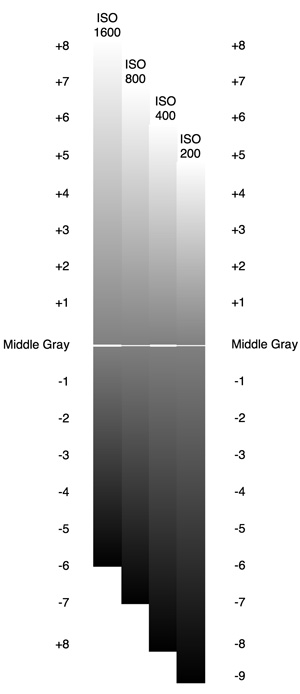

So it was down to the Alexa vs. the Gemini, and the Cookes vs. the Superspeeds. I spent most of Thursday and all of Friday morning playing with the footage in DaVinci Resolve, trying to decide between these two pairs of very close contenders. I tried various LUTs, did some rough grading (very badly, because I’m not a colourist), tested how far I could brighten the footage before it broke down, and examined flares and bokeh obsessively.

Ultimately I chose the Cooke Panchros because (a) they have a beautiful and very natural-looking flare pattern, (b) the bokeh has a slight glow to it which I like, (c) the bokeh remains a nice shape when stopped down, unlike the Superspeeds’, which goes a bit geometric, (d) they seem sharper than the Superspeeds at the edges of frame when wide open, and (e) more lengths are available.

As for the zoom lenses (not included in the video), the Cooke and the Angenieux were very similar indeed. I chose the former because it focuses a little closer and the bokeh again has that nice glow.

I came very close to picking the Gemini as my camera. I think you’d have to say, objectively, it produces a better image than the Alexa, heretical as that may sound. The colours seem more realistic (although we didn’t shoot a colour chart, which was a major oversight) and it grades extremely well. But…

I’m not making a documentary. I want a cinematic look, and while the Gemini is by no means un-cinematic, the Alexa was clearly engineered by people who loved the look of film and strove to recreate it. When comparing the footage with the Godfather and Fanny and Alexander screen-grabs that are the touchstone of the look I want to create, the Alexa was just a little bit closer. My familiarity and comfort level with the Alexa was a factor too, and the ACs felt the same way.

I’m very glad to have tested the Gemini though, and next time I’m called upon to shoot something great and deliver in 4K (not a requirement on this project) I will know exactly where to turn. A couple of interesting things I learnt about it are: (1) whichever resolution (and concomitant crop factor) you select, you can record a down-scaled 2K ProRes file, and this goes for the Helium too; (2) 4K gives the Super-35 field of view, whereas 5K shows more, resulting in some lenses vignetting at this resolution.