It’s time for one of my occasional asides celebrating the world of traditional visual effects – miniatures, matte paintings, rear projection, stop motion and the like. For a film using all of those techniques, look no further than The Abyss (1989). Arguably James Cameron’s most underrated film, it can also be considered his most ambitious. Whereas Terminator 2 had bigger action scenes, Titanic had a bigger set and Avatar had more cutting edge technology, these concerns all pale in comparison to the sheer difficulty of shooting so much material underwater.

The hour-long documentary Under Pressure makes the risks and challenges faced by Cameron and his crew very clear.

The Abyss won an Oscar for Best Visual Effects, and is remembered chiefly for the then-cutting-edge CG water tentacle. But it also ran the gamut of traditional effects techniques.

The film follows the crew of an experimental underwater drilling platform, led by Bud (Ed Harris), as they are roped into helping a team of navy divers, led by Lt. Coffey (Michael Biehn), investigate the sinking of a submarine. Underwater-dwelling aliens and cold war tensions become involved, and soon an unhinged Coffey is setting off in a submersible to dispatch a nuke to the bottom of the Cayman Trench and blow up the extra-terrestrials.

When Bud and his wife Lindsey (Mary Elizabeth Mastrantonio) give chase in a second submersible, a visual effects tour de force ensues. The following methods were used to build the sequence:

- Medium-wide shots of the actors in real submersibles shot in an abandoned power station that had been converted by the production into the world’s largest fresh-water filtered tank, equal in capacity to about eleven Olympic swimming pools.

- Close-ups of the actors in a submersible mock-up on stage.

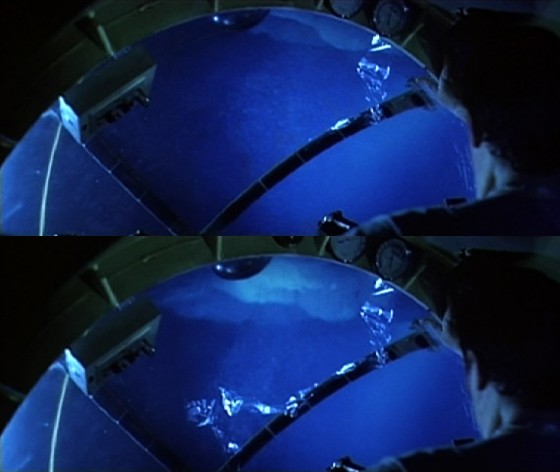

- Over-the-shoulder shots of the actors in the submersible mock-up, with a rear projection screen outside the craft’s dome, showing miniature footage accomplished with….

- Quarter-scale radio-controlled submarines, shot in a smaller tank. These miniatures were remarkably powerful and, due to the lights and batteries on board, weighed around 450lb (204kg). In order to see what they were doing, the operators were underwater as well, using sealed waterproof joysticks to direct the craft. The RC miniatures were used when the craft needed to collide with each other, or with the underwater landscape, and whenever the audience was not going to get a good look at the domes on the front of the submersibles and notice the lack of actors within.

-

One of the custom film projectors inserted into the miniature subs Where a more controlled camera move was required, or the actors needed to be visible inside the subs, but it was not practical to shoot full-scale, motion control was used. This is the same technique used to shoot spaceships in, for example, the original Star Wars trilogy. A computer-controlled camera moves around a static model (or vice versa), exposing film very slowly in order to maintain a large depth of field. The move is repeated several times for each different vehicle under different lighting conditions, before compositing all of the “passes” together on the optical printer in the desired ratios, to achieve the final look. For The Abyss’s motion control work, the illusion of being underwater was created with smoke. In shots featuring the submersibles’ robot arms, stop motion was employed to animate these appendages. But perhaps the neatest trick was in making the miniature subs appear to be inhabited; the models were fitted with tiny projectors which would throw pre-filmed footage of the actors onto a circular screen behind the dome.

The sub chase demonstrates perfectly how visual effects should work: mixing a range of techniques so that the audience never has time to figure out how each one is done, and using an appropriate technique for each individual shot so that you’re making things no more and no less complicated than necessary to tell that little piece of the story.

My favourite effect in the sequence is near the end, when the dome of Coffey’s sub cracks under the water pressure. This was filmed over-the-shoulder using rear projection for the view outside of the dome. But the dome was taken from a real submersible, and as such was too thick and too valuable to be genuinely cracked. So someone, and whoever he or she is is an absolute genius, came up with the idea of using an arrangement of backlit sellotape on the dome to create the appearance of a crack. A flag was then set in front of the backlight, rendering the sellotape invisible. On cue, the flag was slid aside, gradually illuminating the “crack”.

Now that, my friends, is thinking outside the box.