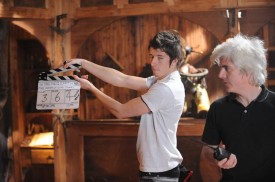

Last weekend I recorded the model shots for Ghost-trainspotting. The script was written with the train miniature from my 2005 feature film Soul Searcher in mind.

This model was built by Jonathan Hayes, with the wheels and linkages by my uncle and my late grandfather, and even some detailing by Yours Truly. If you’ve seen Going to Hell: The Making of Soul Searcher you’ll know what an absolute pain in the arse this train was to shoot back in the autumn of ’04. You can also check out the key blog entries here, here and here to experience the pain.

I’m pleased to report that filming the train this time around was considerably easier. The model has been sitting in my parents’ loft conversion for the last eight years, and that’s where I filmed it. All I had to do was rig some black drapes and line up the camera angles to the live action plates.

In the past, whenever I’ve needed to shoot a VFX element that had to match another, pre-existing element, I’ve used acetate. I would play back the existing element, typically a live action plate from principal photography, on a TV or monitor. I’d tape a sheet of acetate – the stuff teachers used to use on overhead projectors – over the screen and draw around the important landmarks with a felt-tip. Then I’d plug the camera into the same TV and adjust the camera angle until it matched the lines on the acetate. Low-tech, but effective.

Thanks to Magic Lantern – a firmware hack for the Canon HD-DSLRs – there’s now a more elegant solution. Magic Lantern provides a large number of handy features that Canon themselves were too tight or too lazy to include, but there are only two I regularly use: manual white balance, which lets you dial in the colour temperature in degrees kelvin, rather than relying on presets or holding up a white sheet of paper, and crop marks.

On Stop/Eject I used the crop marks to show us the 2:35:1 widescreen aspect ratio we were framing to, but you can actually overlay any monochrome image on the viewfinder by simply creating a .BMP image of the correct specifications on your computer and saving it to your SDHC card. So for Ghost-trainspotting, I loaded still frames from the two live action plates into Photoshop, and outlined them with the paint tool. After saving these outlines to the memory card as bitmaps, I could superimpose them on the Live View image on my Canon 600D’s flip-out screen. This made it a doddle to line up the shots.

So, the model shots are now in the can and yesterday I incorporated them into the film. I also tightened up the edit – finally getting it down to 2’20 exactly, including credits – mixed the audio and graded the images. The film is very nearly finished now; I’m just trying to decide whether to change the ending….

If you’re lucky, there may be a little VFX breakdown of the train shots coming in the next week or so. Meanwhile, here’s a nickel’s worth of free advice about shooting miniatures: