Seven years ago, I transitioned to making a living purely as a director of photography on drama. I’ve since added writing and making an online course to my repertoire, but drama is still paying most of the bills. If you’re doing bits of what you love around a day job in an office, or freelance corporate videos, being able to leave those things behind you and pay the rent with stuff you enjoy doing can seem like the Holy Grail. So below I’m going to list the three things which I think, in combination, allowed me to make that transition.

Seven years ago, I transitioned to making a living purely as a director of photography on drama. I’ve since added writing and making an online course to my repertoire, but drama is still paying most of the bills. If you’re doing bits of what you love around a day job in an office, or freelance corporate videos, being able to leave those things behind you and pay the rent with stuff you enjoy doing can seem like the Holy Grail. So below I’m going to list the three things which I think, in combination, allowed me to make that transition.

1. Quantity of experience: putting in the hard graft

When I stopped doing corporates in 2014, I had been in the industry for a decade and a half. I had made two no-budget features off my own back, and photographed half a dozen other no-budget features and countless shorts, as well as the rent-paying work on participatory films, training videos and web video content. (Whether this kind of stuff really counts as being in “the industry” is debatable, but that’s a subject for another post.)

When I apply for a job I always start by introducing myself as a DP with x years of experience, because I think it speaks volumes about my passion and commitment, and proves that I must have talent and be pleasant to work with, if I’ve been able to keep doing it for so long.

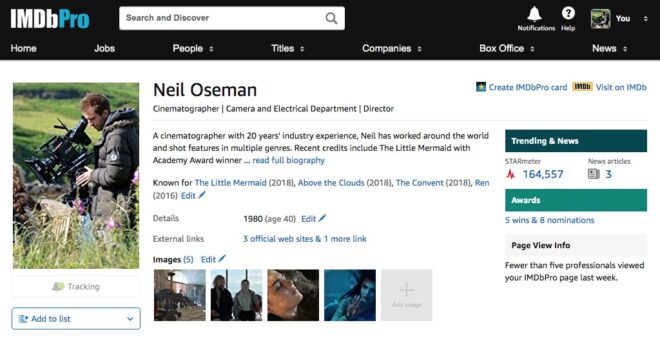

The number of IMDb credits I had is also important. I had almost 50 at the time I made the jump, over half of those as a cinematographer.

How many years of experience and how many IMDb credits you need before you can make the jump could be more or fewer than I needed, depending on the other two factors on this list and the quality of the contacts you make. (I haven’t included contacts as a separate item on this list because it comes naturally out of the jobs you do. Artificially generating contacts, for example by attending networking events, does not lead to jobs or career progression, at least not in my experience.)

2. Quality of experience: getting that killer production on your reel

I first noticed a change occurring in my career when I added material from Ren: The Girl with the Mark to my showreel. There was a noticeable increase in how often I was getting short-listed and selected for jobs. And The First Musketeer, in conjunction with Ren, led directly to my first paid feature film DP gig.

I first noticed a change occurring in my career when I added material from Ren: The Girl with the Mark to my showreel. There was a noticeable increase in how often I was getting short-listed and selected for jobs. And The First Musketeer, in conjunction with Ren, led directly to my first paid feature film DP gig.

What was it about these two projects which enabled them to do for my career what fifteen years’ worth of other no-budget projects couldn’t? Production value. Simple as that. They looked like “real” TV or film, and not in the way that your friends and family will look at anything you shot and go, “Wow, that looks like a real film!” They looked – even to people in the industry – like productions that had serious money behind them. And people are lazy when they’re looking at showreels. If they’re hiring for a job that has serious money behind it, they want to see material on your showreel that appears to have serious money behind it.

Most scripts that you will read for shorts or no-budget features will be written to make them achievable with little or no money. Often they will be set mainly in one house (the director’s, or a bland-looking Airbnb) in the present day, with no production design and only three or four characters. If the script is well written, and you’re an actor, then working on such a project could be great for your career. For most crew members, it’s a waste of time.

For DPs in particular, quality production design is incredibly important on your showreel. Most people who watch your reel won’t really be able to separate the cinematography from the overall look of the piece – the art, the costumes, the make-up, the locations – so getting showreel material that is visually stunning from all departments is the only way to kick your career up to the next level.

3. The Fear: making a living at it because you have to

Before I stopped doing corporates, I thought I was making every effort to get work as a drama DP. But I was wrong. As soon as I gave up the safety net of corporates, my whole attitude to drama work changed. Suddenly I had to do it, and I had to get paid reasonably well for it, otherwise I wouldn’t be able to pay my rent. It made me drive a harder bargain when negotiating my fee, it made me turn down unpaid projects and as a consequence it changed the way producers and directors saw me, and the kinds of projects they would consider me for.

Do not underestimate the value of The Fear. It’s not a magic wand, and you do need to have the experience and the killer production(s) on your reel before you make the jump, but The Fear will give you wings and help you get to the other side.