Stanley Kubrick’s 1975 period epic Barry Lyndon, although indifferently received upon its original release, is considered a masterpiece by many today. This is largely due to its painterly photography with strong, precisely composed frames that leave the viewer feeling more like they’ve wandered through an art gallery than watched a movie. Today I’m going to look at eight methods that Kubrick and his team used to create this feel. It’s an excellent example of how a director with a strong vision can use the many aspects of filmmaking to realise that vision.

1. Storytelling

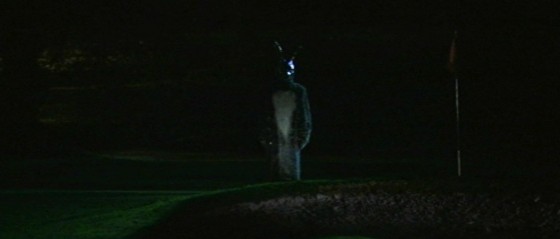

The American Cinematographer article on Barry Lyndon notes that “Kubrick has taken a basically talky novel and magically transformed it into an intensely visual film.” You have only to look at a series of frame-grabs from the movie to see just how much of the story is contained in the images. Just like a painter, Kubrick reveals a wealth of narrative within a single frame. The shot above, for example, while recalling the landscapes of artists like Constable in its background and composition, also clearly tells the story of a courtship threatened by a third party with violent designs.

2. Design

Kubrick was keen for Lyndon to feature the type of rich fabrics which are often seen in 18th century art. He referred costume designer Milena Canonero to various painters of the period. “Stanley wanted beautiful materials,” she recalls in the documentary Stanley Kubrick: A Life in Pictures, “because as he quite rightly said, that’s why in those paintings they gave that wonderful light.”

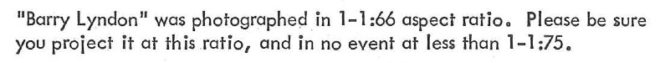

3. Aspect ratio

There was much confusion and controversy surrounding Kubrick’s intended ratio for Lyndon. The negative was apparently hard-masked to 1.6:1, with the result that VHS and DVDs used this ratio, while the images were vertically cropped to 1.78:1 for the later Blu-ray release. However, the discovery in 2011 of a letter from Kubrick to cinema projectionists finally proved that 1.66:1 was the ratio he wanted audiences to see the film in.

1.66:1 was a standard ratio in parts of Europe, but unusual in the UK and USA. It’s not far off the golden ratio (1.6180:1) – a mathematically significant ratio which some artists believe to be aesthetically pleasing. There is evidence that Kubrick was not a fan of wide aspect ratios in general, perhaps because of his background as a photographer, but it can be no coincidence that Lyndon distances itself from the cinematic ratios of 1.85 and 2.39, and instead takes a shape closer to that of a typical painting.

(Most of the images in this post come from Evan Richards’ Cinematographers Index, and he in turn grabbed them from the 1.78:1 Blu-ray. The image above is in 1.66:1 but shows the 1.78:1 crop-lines.)

4. Composition

“The actual compositions of our setups were very authentic to the drawings of the period,” says DP John Alcott, BSC in his interview with American Cinematographer. Perhaps the film’s most obvious compositional nod to classical art is the large amount of headroom seen in the wide shots. As this article by Art Adams explains, the concept of placing the subject’s head at the top of the frame is fairly new in the history of image creation. Plenty of traditional art includes lots of headroom, and Lyndon does the same.

5. Camera movement

There is little camera movement in Barry Lyndon, but there are 36 zoom shots. Unlike a physical dolly move, in which the parallax effect causes different planes of the image to shrink or enlarge at differing rates, a zoom merely magnifies or reduces the whole image as a single element. This of course only serves to enhance the impression of a two-dimensional piece of art. In fact, the zooms resemble nothing so much as the rostrum camera moves a documentary filmmaker might make across a painting – what today we’d call a Ken Burns effect.

It’s interesting to note that, although Barry Lyndon is famous for its fast lenses – the f/0.7 Zeiss Planar primes – the movie also used a very slow lens, a custom-built T9 24-480mm zoom. From various accounts, other zooms used seem to include a Cooke T3.1 20-100mm and possibly a 25-250mm of some description. Of course, none of the zoom lenses were anywhere near fast enough for the candlelit scenes, so in those instances the filmmakers were forced to use a Planar and pull back physically on a dolly.

6. Lighting

“In preparation for Barry Lyndon we studied the lighting effects achieved in the paintings of the Dutch masters,” Alcott says. “In most instances we were trying to create the feeling of natural light within the houses, mostly stately homes, that we used as shooting locations.” The DP closely observed how natural light would come in through the windows and emulate that using diffused mini-brutes outside. This made it possible to shoot long days during the British winter when natural light was in short supply. Last week I covered in detail the technical innovations which allowed Alcott and Kubrick to shoot night scenes with just genuine candlelight, as 18th century painters would have seen and depicted them.

7. Contrast

Film stock in the seventies was quite contrasty, so Alcott employed a few methods to adjust his images to a tonal range more in keeping with 18th century paintings. He used a Tiffen No. 3 Low Contrast Filter at all times, with an additional brown net for the wedding scene “where I wanted to control the highlights on the faces a bit more,” he explains. He also used graduated ND filters (as in the above frame) both outdoors and indoors, if one side of the room was too bright. Most interestingly, he even went so far as to cover white fireplaces and doorways with fine black nets – not on the lens but on the objects themselves.

8. Blocking

The blocking in Barry Lyndon is often static. While this is certainly a creative decision by Kubrick, again recalling painted canvases and their frozen figures, it was also technically necessary in the candlelit scenes. Whenever the f/0.7 lenses were in use, the cast were apparently instructed to move as little as possible, to prevent them going out of focus. As one YouTube commenter points out, the stillness imposed by these lenses mirrors the stillness required of a painter’s model.