Here’s another lighting breakdown from the short film Annabel Lee, which has won many awards at festivals around the world, including seven now for Best Cinematography.

I wanted the cottage to feel like a safe place for Annabel and E early in the film. When they come back inside and discuss going to the village for food, I knew I wanted a bright beam of sunlight coming in somewhere. I also knew that, as is usual for most DPs in most scenes, I wanted the lighting to be short-key, i.e. coming from the opposite of the characters’ eye-lines to the camera. The blocking of the scene made this difficult though, with Annabel and E standing against a wall and closed door. In the story the cottage does not have working electricity, so I couldn’t imply a ceiling light behind them to edge them out from the wall. Normally I would have suggested to the director, Amy Coop, that we flip things around and wedge the camera in between the cast and the wall so that we could use the depth of the kitchen as a background and the kitchen window as the source of key-light. But it had been agreed with the art department that we would never show the kitchen, which had not been dressed and was full of catering supplies.

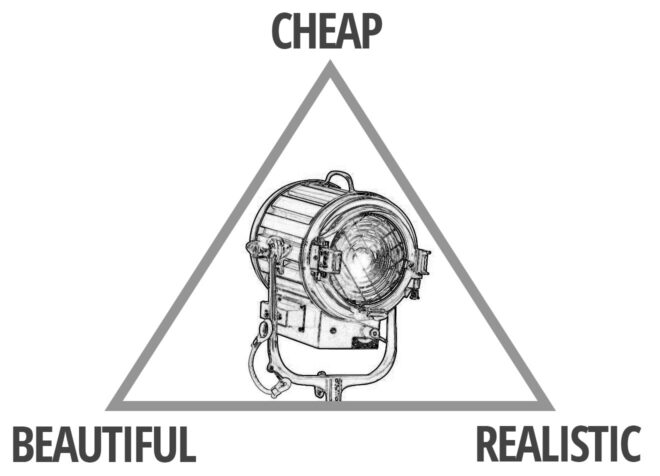

The solution was firing a 2.5K HMI in through one of the dining room windows to create a bright rectangle of light on the white wall. This rectangle of bounce became the source of key-light for the scene. We added a matt silver bounce board just out of the bottom of frame on the two-shot, and clamped silver card to the door for the close-ups, to increase the amount of bounce. The unseen kitchen window (behind camera in the two-shot) was blacked out to create contrast. I particularly like E’s close-up, where the diffuse light coming from the HMI’s beam in the haze gives him a lovely rim (stop sniggering).

Adding to the fun was the fact that it was a Steadicam scene. The two-shot had to follow E through into the dining room, almost all of which would be seen on camera, and end on a new two-shot. We put our second 2.5K outside the smaller window (camera left in the shot below), firing through a diffusion frame, to bring up the level in the room. I think we might have put an LED panel outside the bigger window, but it didn’t really do anything useful without coming into shot.

For more on the cinematography of Annabel Lee, visit these links: