This week issue 40 of Infinity magazine comes out, featuring a couple of articles I wrote, including one about the cult sci-fi series Quantum Leap. The show saw Dr. Sam Beckett (Scott Bakula) bouncing around time into other people’s bodies and striving to put right what once went wrong, while his holographic friend Al (Dean Stockwell) smoked cigars, letched, and relayed exposition from Ziggy the computer.

I end the article by wondering whether it’s time for someone like Netflix to bring the show back (it definitely is). What I don’t mention in the magazine is that – unbeknownst to almost everyone – Quantum Leap has already been rebooted once.

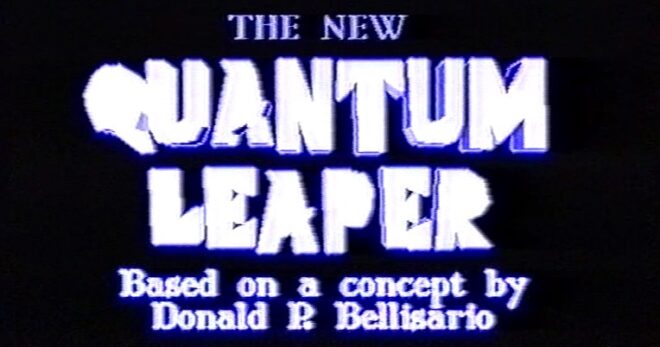

This, my loyal readers, is the story of Quantum Leaper.

Season One (1995)

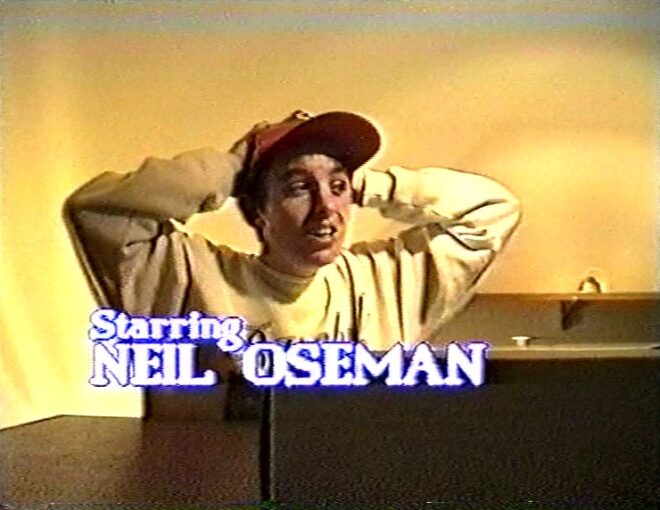

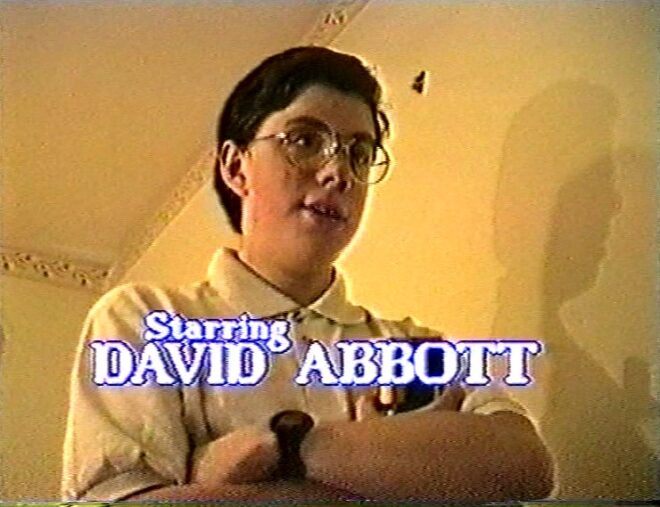

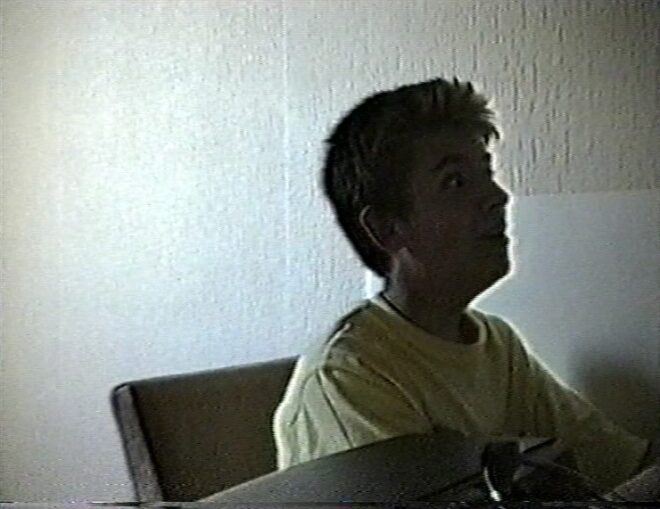

As teenagers, my friend David Abbott and I were huge Quantum Leap fans, and were bereft when the show was axed in 1993. I was developing an interest in filmmaking, having dabbled in 2D computer animation on my Atari ST and borrowed my grandfather’s Video-8 camcorder on a couple of occasions. When I was given that camcorder for my 15th birthday, David and I decided that we would make our own version of Quantum Leap, which we imaginatively titled Quantum Leaper.

The first episode was called “Just What the Doctor Ordered” and saw my character – named, again with great imagination, Neil – leaping into a doctor just as his patient is flatlining. I don’t remember much about the plot, but I do remember that we climbed the nearby Malvern Hills to film a fight scene.

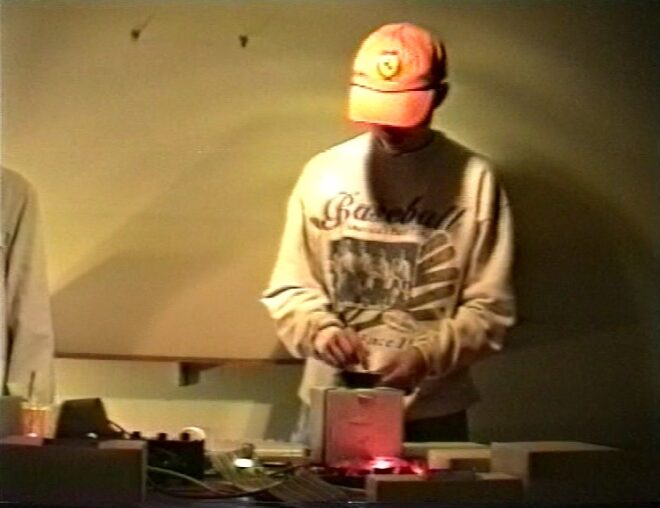

Dave played Albert, my holographic helper, communicating with Project Quantum Leap’s supercomputer Ziggy by means of a special hand-link, just like Dean Stockwell did. Unlike Dean Stockwell’s, this hand-link was a calculator.

The two of us also played all the supporting characters (often with the judicious addition of a hat or jacket) and operated the camera, unless we were both in shot, in which case it was locked off. Much of the the editing was done in camera – rewinding the 8mm videotape, cueing it up to the exact moment the last piece of action ended, then hitting record and calling action simultaneously – and the rest I did tape-to-tape with two VCRs connected together. A cheap four-track disco mixer enabled the addition of music (badly composed by me) and sound effects (many of which were sampled from Quantum Leap itself). As YouTube was still years away, the only viewers for the series were our parents and friends, forced to sit down in front of the TV and watch it off VHS.

Episode two, “Boom!”, saw the fictional Neil as a bomb disposal expert supposedly in Northern Ireland in 1980, though like the first episode it was all shot in and around my house. My sister Kate was drafted in to play a journalist whose life Neil has to save.

“A Leap into the Blue” was the next episode, with Neil in the body of a parachutist. Scenes of characters in free-fall were shot with us standing in front of a white wall; I digitised the footage on my ST with a Videomaster cartridge and composited scrolling clouds into the background. The resolution of the Videomaster was very limited – maybe 320×240 – the frame rate was very low too, and it could only do black and white.

Next we shot a “pilot” episode explaining how Neil and Albert switched places with Sam and Al. I remember digitising shots of Scott Bakula and Dean Stockwell from Quantum Leap and compositing them atrociously into our own footage. At about 30 minutes long, the pilot was double the length of our other episodes.

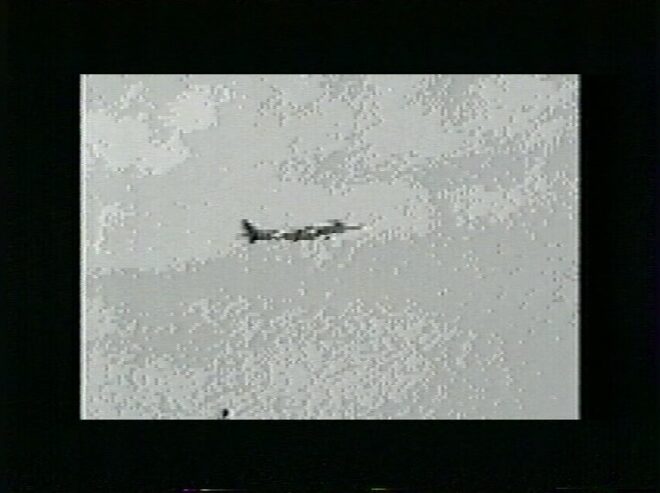

Then we continued the series where we’d left off. Dave’s script “One Giant Leap” has Neil on a space shuttle mission, an episode that included NASA footage taped off the TV. We made almost no attempt to create sets; the space shuttle cockpit was a plain wall, a computer keyboard and a piece of card to cover an incongruous bookcase.

The next two episodes find Neil meeting (and shooting) an evil future version of himself, then leaping into the crazy future space year of 2017. The latter involves a flying car – my mum’s Citroen AX with the wheels framed out, intercut with an extremely crude CGI model.

Dave’s episodes “Virtual Leaping” and “Bullets Over Leaping” see Neil become a VR programmer (with a headset made of Lego) and then an actor (in a studio suspiciously like Dave’s shed).

My next episode has Neil leaping into himself and saving his father’s life. (My actual dad provided some splendidly wooden acting.) But doing this causes a paradox, and the season finale sees Neil and Albert swap places (as Sam and Al do in a classic Quantum Leap episode) and Neil having to restore the timeline to prevent the destruction of the universe.

We were ambitious. You can say that much for us.

Season Two (1996)

The following year, while doing our GCSEs, we began work on a second season. In between I’d made a bad 40-minute comedy, Bob the Barbarian, and an appalling feature-length sci-fi film, The Dark Side of the Earth, and I’d learnt a few things that would lift the production values of Season Two very slightly. I’d also nagged my parents into buying me a genlock which would let me superimpose CGI over analogue video, meaning I didn’t have to digitise footage and suffer the horrendous image degradation any more.

The actual Quantum Leaping effect from this era of the show is surprisingly decent given the equipment we were working with. We would lock the camera off and jump-cut to a blue filter being over the lens, then a white glow would creep over me – an animation I achieved in software called Deluxe Paint – followed by tendrils of electricity. The screen would then fade to white and a similar effect would play out in reverse to show the leap in.

Another improvement was that we managed to convince a few other friends to act in the series, including fellow Quantum Leap fan Lee Richardson, as well as Chris Jenkins, Conrad Allen, Matt Hodges, Si Timbrell and Jim McKelvie. Recognising my lack of musical talent at last, I abandoned composing and instead used soundtrack CDs from Star Trek: Deep Space Nine (Dennis McCarthy), the John Woo film Broken Arrow (Hans Zimmer), and the Doctor Who story “The Curse of Fenric” (Mark Ayres). Albert’s hand-link prop got an upgrade too, from a calculator to a custom Lego build with flashing lights.

Season Two opens with Dave’s episodes “Project Hijacked” and “Oh Brother, Where Art Thou?” which focus on events at Project Quantum Leap, supposedly a high-tech facility in the New Mexico desert in 2005. In reality it was a living room with a control console made out of painted cardboard boxes and Christmas lights. In an early manifestation of my cinematography leanings, I snooted the ceiling light with a rolled-up piece of silver card, lending a little bit of mood to the look.

At the time, Dave’s family were training a hearing dog, Louis, so I wrote an episode to feature him; “Silence is Golden” sees Neil leap into a deaf man, and was followed by the morbid “Ashes to Ashes” where he leaps into a corpse.

The next episode, Dave’s “Driven to Distraction”, is probably the best of the lot. For once there were few enough characters that no-one needed to confusingly play dual roles, and there is plenty of action to boot. (I uploaded this episode to YouTube so long ago that the ten-minute time limit still applied.)

The X-Files-inspired “Close Encounters of the Leaping Kind” comes next, with Neil as a ufologist bothered by a shadowy government agent. Then Neil becomes a teenager who must prevent a drugs overdose, then a one-armed man who must overcome prejudice to hold down a job. Cringingly entitled “Not So Armless”, this latter was shot in a newsagent’s owned by a friend’s parents, one of the series’ few non-domestic locations.

Like Quantum Leap we had a mirror shot in every episode where Neil would see the leapee’s reflection looking back at him. Sometimes Dave would track the camera behind my back and we’d hide a cut in the darkness to swap me with whoever was playing the reflection. Another time we pretended the serving hatch in Dave’s house was a mirror and the two of us synchronised our movements. For a fight scene in “Not So Armless” Chris hid one arm inside his t-shirt so that Neil’s mirror image could appear to punch the antagonist with an invisible fist!

The penultimate episode of the season features several brief leaps, ending with one to Hiroshima in 1945, where the A-bomb detonation (more footage off the TV) causes both Neil and Albert to leap simultaneously. In the finale, Albert becomes a mountaineer caught in an avalanche, while Neil is a member of the rescue team – a premise thieved from the Quantum Leap novel “Search and Rescue”. We started shooting it during snowy weather, but the snow thawed and the episode was never completed. The friends who had been appearing as supporting characters now had part-time jobs and couldn’t spare the time for filming.

Legacy

We wrote all six episodes of a third season which would have explained how Neil became the evil future version of himself seen in an earlier episode, but nothing was ever filmed.

In 1997 we began a remake of the pilot using the experience we had gained since shooting the original, but again it was never completed. One part we did film was an action sequence with me on the roof rack of a car while the driver swerves around trying to throw me off. We shot this on Malvern’s Castlemorton Common and used a dummy of me for some of the wider and more dangerous shots. Its acting was probably better than mine. We remade the scene four years later as part of my Mini-DV feature The Beacon.

Today only five of the 20 Quantum Leaper episodes that we made survive, the rest having been callously taped over at some point in my late teens. That’s probably for the best, as most of it was hilariously bad, but making it taught me a hell of a lot about filmmaking. Without it, I doubt I’d have a career in cinematography today.