Last week, Greig Fraser, ASC, ACS and Baz Idoine were awarded the Emmy for Outstanding Cinematography for a Single-camera Series (Half-hour) for The Mandalorian. I haven’t yet seen this Star Wars TV series, but I’ve heard and read plenty about it, and to call it a revolution in filmmaking is not hyperbole.

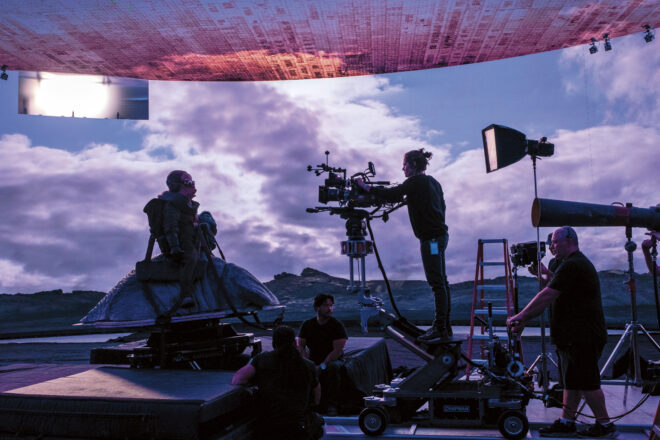

Half of the series was not shot on location or on sets, but on something called a volume: a stage with walls and ceiling made of LED screens, 20ft tall, 75ft across and encompassing 270° of the space. I’ve written before about using large video screens to provide backgrounds in limited aways, outside of train windows for example, and using them as sources of interactive light, but the volume takes things to a whole new level.

In the past, the drawback of the technology has been one of perspective; it’s a flat, two-dimensional screen. Any camera movement revealed this immediately, because of the lack of parallax. So these screens tended to be kept to the deep background, with limited camera movement, or with plenty of real people and objects in the foreground to draw the eye. The footage shown on the screens was pre-filmed or pre-rendered, just video files being played back.

The Mandalorian‘s system, run by multiple computers simultaneously, is much cleverer. Rather than a video clip, everything is rendered in real time from a pre-built 3D environment known as a load, running on software developed for the gaming industry called Unreal Engine. Around the stage are a number of witness cameras which use infra-red to monitor the movements of the cinema camera in the same way that an actor is performance-captured for a film like Avatar. The data is fed into Unreal Engine, which generates the correct shifts in perspective and sends them to the video walls in real time. The result is that the flat screen appears, from the cinema camera’s point of view, to have all the depth and distance required for the scene.

The loads are created by CG arists working to the production designer’s instructions, and textured with photographs taken at real locations around the world. In at least one case, a miniature set was built by the art department and then digitised. The scene is lit with virtual lights by the DP – all this still during preproduction.

The volume’s 270° of screens, plus two supplementary, moveable screens in the 90° gap behind camera, are big enough and bright enough that they provide most or all of the illumination required to film under. The advantages are obvious. “We can create a perfect environment where you have two minutes to sunset frozen in time for an entire ten-hour day,” Idoine explains. “If we need to do a turnaround, we merely rotate the sky and background, and we’re ready to shoot!”

Traditional lighting fixtures are used minimally on the volume, usually for hard light, which the omni-directional pixels of an LED screen can never reproduce. If the DPs require soft sources beyond what is built into the load, the technicians can turn any off-camera part of the video screens into an area of whatever colour and brightness are required – a virtual white poly-board or black solid, for example.

A key reason for choosing the volume technology was the reflective nature of the eponymous Mandalorian’s armour. Had the series been shot on a green-screen, reflections in his shiny helmet would have been a nightmare for the compositing team. The volume is also much more actor- and filmmaker-friendly; it’s better for everyone when you can capture things in-camera, rather than trying to imagine what they will look like after postproduction. “It gives the control of cinematography back to the cinematographer,” Idoine remarks. VR headsets mean that he and the director can even do a virtual recce.

The Mandalorian shoots on the Arri Alexa LF (large format), giving a shallow depth of field which helps to avoid moiré problems with the video wall. To ensure accurate chromatic reproduction, the wall was calibrated to the Alexa LF’s colour filter array.

Although the whole system was expensive to set up, once up and running it’s easy to imagine how quickly and cheaply the filmmakers can shoot on any given “set”. The volume has limitations, of course. If the cast need to get within a few feet of a wall, for example, or walk through a door, then that set-piece has to be real. If a scene calls for a lot of direct sunlight, then the crew move outside to the studio backlot. But undoubtedly this technology will improve rapidly, so that it won’t be long before we see films and TV episodes shot entirely on volumes. Perhaps one day it could overtake traditional production methods?