If you’re a fan of early Steven Spielberg films, you’ve probably heard of split diopter shots (also spelt “dioptre” in the UK). Brian de Palma used them a lot too, and Robert Wise’s Star Trek: The Motion Picture is absolutely riddled with them.

A split diopter allows half the image to be focused at one distance and half at another. Shallow depth of field is sought after by many filmmakers today, but it wasn’t always so popular. Sometimes a director or DP wanted both characters in a deep two-shot simultaneously in focus, and slow film stock and/or lenses meant that it wasn’t possible to just stop down the iris.

So what is a split diopter (a.k.a. split-field diopter)? It’s a convex lens of a semi-circular shape that can be slotted into your matte box. Light passing through this lens is converged so that it focuses closer, while light passing through the empty half of course goes unaltered to the main lens.

So what is a split diopter (a.k.a. split-field diopter)? It’s a convex lens of a semi-circular shape that can be slotted into your matte box. Light passing through this lens is converged so that it focuses closer, while light passing through the empty half of course goes unaltered to the main lens.

Bog-standard diopters are available too, with no missing half, enabling the entire image to be focused closer than normal. (In stills photography they are sometimes called close-up lenses or macro filters.) These are especially useful with anamorphic and zoom lenses, which tend to have greater close-focus distances than spherical primes. There’s no stop loss, so you don’t have to compensate with more light.

I carried a set of diopters with me on Hamlet and we used them for a couple of shots with the vintage Cooke Cinetal 25-250mm zoom (CF: 5’6″) when I was shooting quite tight and quite close to the talent.

So that’s what the physical object is. But a diopter is also a unit of measurement. A typical set of physical diopters (full or split) contains ½, 1, 2 and 3 strengths. What do those numbers mean?

A diopter is defined as a reciprocal metre, or 1 over the focal length. It’s the same unit used to define prescriptions for glasses. The important thing in cinematography is what effect a diopter of a given strength has on your minimum and maximum focus distances. Apps like pCAM Pro will work these out for you, but let’s do the maths ourselves because it’s my blog and I said so.

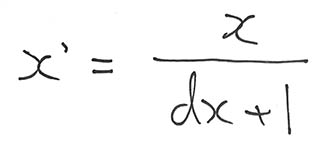

The formula for minimum focal distance is

where

- x is the normal minimum focus of the lens (in metres),

- x’ is the new minimum focus,

- and d is the strength of the diopter.

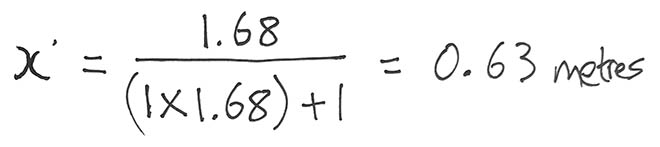

Let’s take my Cooke Cinetal as an example. The 5’6″ close focus in metres is 1.68, so with a number 1 diopter…

… or with a number 3 diopter…

Diopters can be stacked; simply add the strengths together and then drop that number into the formula, so in the above case we’d have a total of 4 diopters (diopters the units, not diopters the objects!) which would produce a close focus of 0.22m. Keep the strongest diopter closest to the camera when stacking.

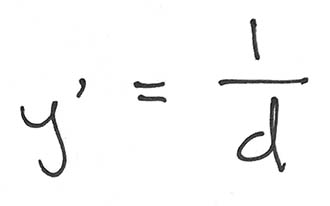

You have to be careful that you don’t reduce your maximum focal distance too much and find you can’t hold focus on a character as they move away. Your new maximum focal distance y’ (when the main lens is set to infinity) is

So that would be 1m with a number 1 diopter! Pretty restrictive, huh? A number 3 diopter gives you a maximum focal distance of 0.33m, even worse! I remember having to cheat Ian McKellen (CLANG!!!) a little closer to camera when we did a diopter shot on Hamlet, so that we could pull focus to him from a foreground actor’s hands.

If you bear that caveat in mind, however, a set of diopters is a very useful thing to have with you.