There is a huge range of glass available to filmmakers today – everything from vintage cinema lenses from the 60s to modern stills glass made for DSLRs. How can a DP choose which is right for their production?

Mount

The first thing to take into account is the lens mount on your camera. If it is PL mount you will have access to a huge range of cinema lenses, some of them with decades of movie history. Other mounts such as Canon EF also provide plenty of choice, but mainly glass aimed at stills rather than cinematography. Some lenses can be mount-converted, some cameras can switch mounts, and adapters are available too, but it’s important to know upfront which lenses are going to be ruled out by your camera choice and which aren’t.

Spherical or Anamorphic

Anamorphic lenses squeeze the image horizontally, to be unsqueezed in post-production. The results are a wider picture, distinctive oval bokeh (out of focus areas) and often lens flares with horizontal streaks in them. This look is very cinematic, but anamorphic lenses tend to be bigger, heavier, more expensive, need more light than and don’t focus as close as their spherical counterparts, so think carefully before you choose them.

Speed

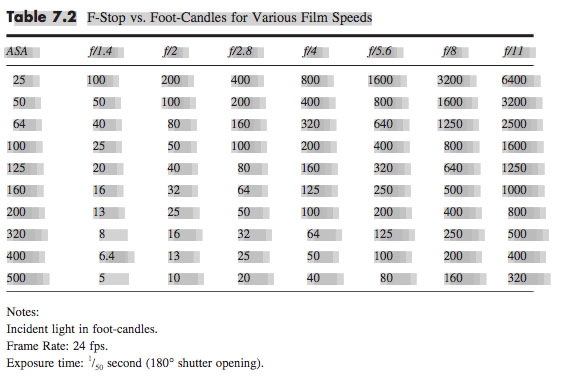

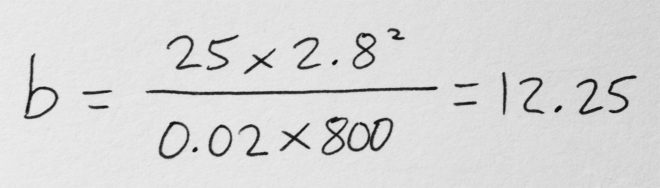

The speed of a lens – i.e. its maximum aperture – is one of its most important characteristics. A fast prime lens might open to T1.4, while a zoom or anamorphic prime might only go to T4. That’s three stops’ difference, equating to eight times more light required by the T4 lens. That can have a big impact on the size and number of lights you need. The ISO you plan to shoot at will also factor into this, of course.

Also consider how deep or shallow a depth of field you want. If you’re after super-blurry backgrounds, only a fast lens will give you those (though shooting on a large-format camera will help). This brings us to…

Bokeh

Bokeh is the appearance of out-of-focus areas in your image. It is most noticeable in small highlights such as fairy lights, which generally turn into big circles when they’re out of focus. Just how big and how smoothly circular depends on the lens and the aperture settings. Some lenses will have more geometric bokeh, octagons for example, which is a result of the shape and number of iris blades within. The bokeh may look rounder when the lens is wide open and more geometric when it is stopped down, or vice versa. It will also have a different shape at the edges of frame. What this comes down to is what look you feel is most aesthetically pleasing or appropriate for your story.

Lens Flares

Another aesthetic choice. How much does the lens flare when light shines straight into it? What about when the light is just out of frame? Is there much veiling flare – an overall milkiness to the image? Do you like the colours and shapes of the flare? Do they feel natural or intrusive, and which is most fitting for the tone of your piece?

Sharpness

This is an important factor with the resolutions of cameras ever increasing. Any decent lens will be sharp at T5.6, but the more you open the iris the more you might start to see the image softening, especially when it is wide open (or conversely when it is stopped down to its minimum aperture). Check also the edges of frame, which may be less sharp than the centre, especially on a vintage or anamorphic lens. If you plan to do a lot of central framing then soft edges may not matter, or may even help to draw the viewer’s eye to the subject, but if you plan to put your subjects at the extreme sides of the frame then you should be careful what lenses you select.

Breathing

A lens is said to breathe when pulling the focus makes the image zoom in or out slightly. It is most noticeable with zoom lenses, some stills lenses and older glass. If you are racking back and forth between the characters in a deep two-shot, lens breathing can become very distracting.

Other Considerations

Other things to look out for are diffraction spikes, the star effect that happens around bright light sources, and colour rendition, which can vary slightly from lens to lens. If you expect to be physically close to your subject you should note the minimum focus distance of the lenses, which will be different for each length in the series. Also consider what focal lengths your chosen lens series contains – are there enough different lengths to cover everything you hope to shoot, especially at the shortest and longest ends of the range?

If you’re still not sure where to start, test footage and comparison videos of different lenses can be found online, like this one I made in 2017:

Better still, ask a rental house if you can come in for a day and shoot your own tests.

See also: