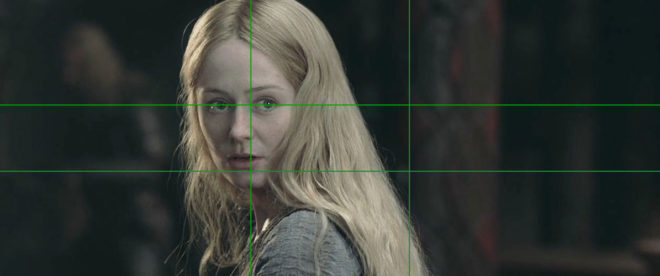

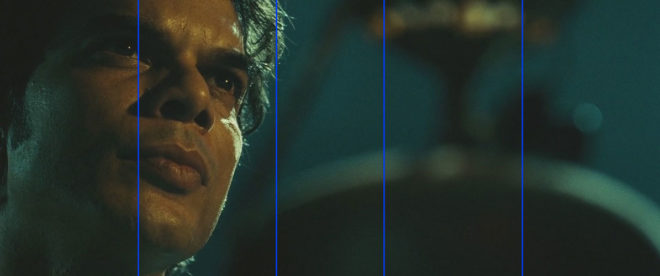

I used to be a casual follower of superhero films, until I was inducted into the Marvel Cinematic Universe via a movie marathon. Despite different directors for each instalment, the MCU has a fairly consistent look and feel, so I was a little surprised when we got to The Avengers to note that it differs visually in one significant way from all of its predecessors. Whereas the five previous films (and indeed most of the subsequent ones) were in the 2.39:1 aspect ratio, The Avengers was presented in the taller 1.85:1 ratio.

This initially struck me as counterintuitive. 2.39:1 was introduced in the 1950s to tempt watchers of the new-fangled TV back into the cinemas, and ever since then it has been associated with the biggest, most epic, most cinematic of movies. It seems like the natural choice for a superhero franchise, so it’s no surprise that the MCU adopted this ratio for most of its instalments. But if wider images mean a more epic movie, then surely The Avengers, the climax of Phase One and the coming-together of a whole team of superheroes, should be, if anything, even wider than its 2.39:1 predecessors?

I’m certainly not the first person to be nonplussed by the choice. A quick google later on threw up plenty of forums where fans complained that The Avengers was “not cinematic enough” because of its aspect ratio. Some linked the choice of ratio to director Joss Whedon’s TV background, claiming he was more comfortable with that shape of frame.

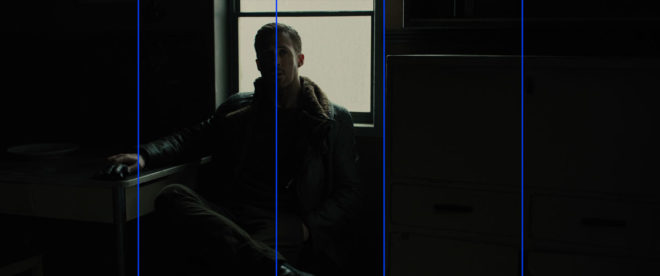

The real reason for Whedon’s decision became clear as the action ramped up into the third act. The battle of New York is not a two-dimensional conflict; Thor and Iron Man are flying around, the Hulk climbs up buildings, the Chitauri ships float above the streets, and Stark Tower plays a key part in the action. The extra frame height of 1.85 was essential to tell that story.

“I wanted to feel the space around us, and use wider lenses,” said Whedon. “That’s why I went 1.85 instead of wider. In IMAX, I wanted it to fill your eyeball completely.”

Continuing the movie marathon, the MCU does not return to 1.85 until Ant-Man, and director Peyton Reed initially encountered resistance from the studio when he advocated this ratio. “It’s a big conversation because it affects production design. It affects everything. And it felt to me… that shrinking was a vertical act and it was going to serve the movie even more. And I had to make a case for the fact that it was still going to be epic.”

I wonder if the days of wider aspect ratios being perceived as more epic are numbered. IMAX sequences are becoming more and more common in blockbusters, including the Marvel films. Digital IMAX has an aspect ratio of 1.90:1, very similar to the 1.85 which is so often perceived as the small-scale, poor man’s ratio. (To confuse matters, the 1.90 sequences are often cropped to 2.39 for ordinary cinemas and home entertainment release.) An epic feel is very much what the IMAX brand is selling, so the traditional perception is being turned on its head. Both Avengers: Infinity War and the recent Endgame were shot entirely in Imax 1.90:1, and are sure to be the very definition of epic for a while to come.

Things seem to be going the same way over in the DC universe too. On the social media platform Vevo, director Zak Snyder had this to say about Batman v. Superman and Justice League: “I had so much fun shooting the IMAX sections of my movie (BvS) [that I] sort of fell in love with that giant less rectangular aspect ratio and so that’s why I shot JL 1:85”.

Image size may have something to do with this shifting trend. After all, a larger image is surely more epic than a smaller one. In theory, 2.39 should result in the largest image, with curtains or masks at the sides of a cinema screen opening up for these widescreen presentations. In practice though, many smaller multiplex auditoria mask the top and bottom of their screens for 2.39, making for a smaller overall image than 1.85, just like when you watch 2.39 content at home on your TV or monitor (which is 1.78:1). My local multiplex recently converted its largest auditorium to IMAX, which involved no change to the width of the screen, but an increase in height.

Add to this the fact that 2.39 overtook 1.85 as the most common aspect ratio for top-grossing films over a decade ago, and it’s small wonder that filmmakers seeking to make their work stand out from the crowd are turning to taller frames.

However the trend of aspect ratios ends up going, it’s important to remember that there’s no wrong or right. I’ve done jobs where directors have told me, “It’s a movie, it’s got to be 2.39,” or, “It’s a series, it’s got to be 1.78,” but there is always a choice. Are your sets tall or wide? Are your lead characters similar or dissimilar in height? Are landscapes or body language most important to this story? It’s factors like these that should really determine the best ratio for your movie, just as Whedon and Reed both realised.

See also: