Back in February 2019 I spent a long day in Black Park, a forest behind Pinewood Studio, shooting a short film called Alder for director Vanda Ladeira. A little late perhaps, but here are my reflections on the cinematography and general experience of making this experimental fairytale.

Back in February 2019 I spent a long day in Black Park, a forest behind Pinewood Studio, shooting a short film called Alder for director Vanda Ladeira. A little late perhaps, but here are my reflections on the cinematography and general experience of making this experimental fairytale.

The film is about a forager (Odne Stenseth) who does not realise he is being watched by the very spirit of the forest, the titular Alder (Libby Welsh). As he cuts a sprig of holly, or steps on a mushroom, he is unknowingly causing her pain. Meanwhile a group of ghosts – Alder’s former victims? – cavort in the woodland, and strips of film made with ground-up human bone reach out from the trees to ensnare the forager.

Vanda contacted me after seeing my work on Ren: The Girl with the Mark. She was keen for Alder’s lair to have the same feel as Karn’s house in that series. We had a number of meetings to discuss the tone, visuals and the logistics of the shoot, which initially was going to take place over two days but was eventually compressed to one.

In October 2018 we conducted a recce in a forest that we ultimately weren’t able to use. I remember at the time that I was considering shooting the project on celluloid, tying in with the plot point about Alder making film from her victims’ bones. I dropped the idea after taking light readings on that recce – when it was very overcast – and realising just how dark it could be under the tree canopy.

We ultimately shot on a Blackmagic Ursa Mini and Xeen primes, provided along with the lighting kit by gaffer Jeremy Dawson. The Blackmagic sensors seem to do very well with earthy tones, as I noticed on the village set of Ren, and the Ursa rendered the browns of the bracken, the soil and the forager’s costume nicely. Jeremy also provided us with a jib which enabled us to underscore the forager’s action with some definite moves: an introductory crane down; a dramatic pull up as he drives his knife into a tree; and a frantic boom down with him as he searches for his lost compass. In Alder’s lair we kept the camera drifting from side to side or up and down to bring energy to her more static scenes.

Lighting for the forager’s scenes was all natural, with just a little bounce or negative fill from time to time to keep some shape to the image. An Artem smoke gun, operated by Claire Finn, was used on almost every shot to give the forest some life and mystery, and also to keep the backgrounds from getting too busy; the grey wall of smoke serves to fade the background slightly, keeping the eye focused on the foreground action.

As there was no dialogue, I was free to change the frame rate expressively. Examples include: over-cranking close-ups of the forager’s feet and hands in contact with nature, emphasing the sensuality of his unwitting connection to Alder; over-cranking the dance of the ghosts to make their movements even more beautiful and supernatural; and under-cranking the forager slightly to enhance his panic when he finds himself lost and surrounded.

Alder’s lair was a set built by Denisa Dumitrescu in the forest. I took broadly the same approach to lighting it as I had for the reference scene from Ren, making some holes in the branch-covered roof and shining a blinder (a bank of four LED spotlights) through it to produce dappled shafts of sunlight. On the floor around Alder were a number of candles; we beefed up the light from these by skipping an 800W tungsten lamp off a bounce board on the floor.

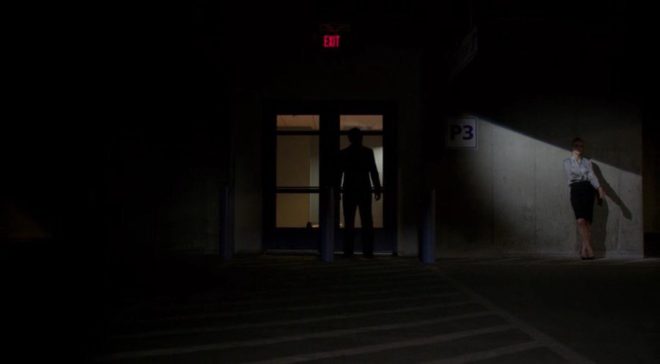

The biggest challenge was the meeting between the two main characters, a scene scripted for daylight which we were forced to shoot after dark due to running behind schedule. It was the longest and most important scene in the film and suddenly the cinematography had to be completely improvised. We did not have anywhere near the lighting package that a woodland night exterior normally calls for – just 800W tungsten lamps, a few LED fixtures, and a generator only powerful enough to run one of each.

What I ended up doing was putting an 800 in the background, ostensibly as a setting sun, and bouncing a blinder off poly-board as fill. We shot the whole scene through in a single handheld shot, once with smoke and once without, then picked up a few close-ups.I tried to hide the lack of light in the background by allowing the 800 to flare the lens and render the smoke almost impenetrable at times. Vanda and her editor, Tom Chandler, leant into the strange, stylised look and bravely intercut the smoky and smokeless takes. The result is much more magical and expressive than what we would have shot if we had still had daylight.

You can watch the finished film here. It won me Best Cinematographer at the New York Cinematography Awards (August 2019) and Film Craft Award: Cinematography at Play Short International Film Awards (2019).