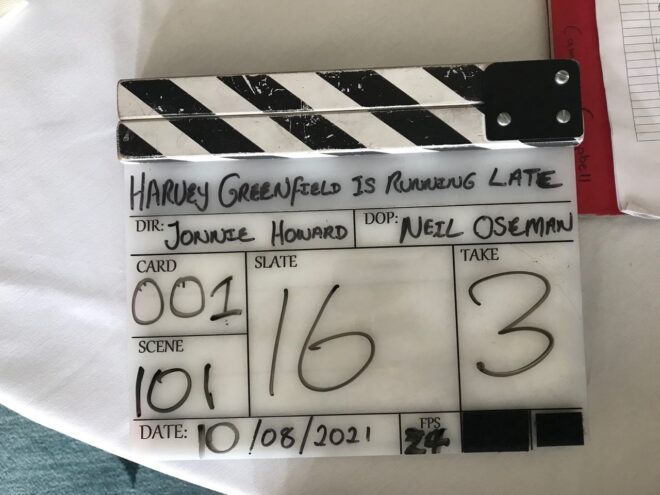

Day 1

The weather was dry and overcast, shedding a pleasantly soft light on the proceedings as the crew of Harvey Greenfield is Running Late set up for our first scene, in front of a small primary school in rural Cambridgeshire.

Then we started shooting and the weather went bananas.

One moment we had bright sunshine, the next we had heavy rain bordering on hail… sometimes in the same take. We had lots of fun and games dodging the showers, maneouvering a 12×12′ silk to soften the sun, keeping reflections and shadows out of shot, waiting for noisy trains to pass, and trying to get through takes without the light changing. But we got there in the end.

In the afternoon we moved into the school hall, which we were using as a makeshift studio. As well as numerous flashbacks, the film includes several imaginary sequences, including a spoof advert. This we shot against a black backdrop using dual backlights, one on either side, to highlight the talent. I totally stole this look from the Men in Black poster.

Our last shot of the day was Harvey’s first, and another imaginary scene, this time set in a coffin. To give the appearance of it being underground, the coffin (with no lid and one side missing) was placed on rostra with a black drape hanging below it. To create darkness above it, we simply set a flag in front of camera. Harvey (Paul Richards) lights a match to illuminate himself, which gaffer Stephen Allwright supplemented with two 1×1′ Aladdin Bi-flexes set to tungsten and gelled even more orange.

Day 2

One of the few occasions in my life when I’ve been able to walk to set from home: we started at the University Arms Hotel overlooking Parker’s Piece, one of Cambridge’s many green spaces (and, fact fans, the place where the rules of Association Football were first established).

The hotel’s function room was dressed as an upmarket restaurant, where we captured Harvey’s first date with his girlfriend Alice (Liz Todd). We shot towards a window; putting your main light source in the background is always a good move, and it gave us the perfect excuse to do soft cross-backlight on the two characters. The room’s wood panelling and sconces looked great on camera too.

The unit then moved to Emmaus, a large charity shop north of the city, where we filmed a Wall of Pants and some tightly choreographed Sandwich Action. Here we broke out the Astera tubes for the fist time, using them as a toppy, fluorescent-style key-light and backlight.

By now we were getting into the visual rhythm of the film, embracing wide angles (our 18-35mm zoom gets heavy use), central framing (or sometimes short-siding), Wes Anderson-type pans/tilts, and a 14mm lens and/or handheld moves for crazier moments.

Day 3

We were based at Paul’s house for day 3, beginning in the street outside for a brief scene in his car. Shooting from the back, we mounted an Aladdin in the passenger seat to key Paul, and blacked out some of the rear windows to create negative fill, much like I did for the driving scenes in Above the Clouds.

The rest of the day was spent in and around Paul’s shed. Or, to be more specific, the middle one of his three sheds. This is Harvey’s “Happy Place” so I stepped up from the Soft FX 0.5 filter I’d been shooting with so far to the Soft FX 1, to diffuse the image a little more. We also used haze for the only time on the film.

Some shots through the shed window gave us the usual reflection challenges. Stephen rigged a 12×12 black solid to help with this, and we draped some bolton over the camera. Inside the shed we used an Aladdin to bring up the level, and once we stopped shooting through the window we fired a tungsten 2K in through there instead. This was gelled with just half CTB so that it would still be warm compared with the daylight, and Stephen swapped the solid for a silk to keep the natural light consistent and eliminate the real direct sun.

I made my first use of the Red Gemini’s low light mode today, switching to ISO 3200 to maintain the depth of field when filming in slow motion. (I have been shooting at T4-5.6 because a sharper, busier background feels more stressful for Harvey.)

Day 4

Back to the primary school. We spent the morning outside shooting flashbacks with some talented child actors from the Pauline Quirke Academy. We got some nice slider shots and comedy pans while dealing with the ever-changing cloud cover.

Inside in the afternoon we picked up a dropped scene from day 1, then moved on to one of the film’s biggest challenges: a six-minute dialogue scene travelling through a corridor and around a classroom, to be filmed in a single continuous Steadicam shot. This could easily have been a nightmare, but a number of factors worked in our favour. Firstly, we had rehearsed the scene on location with actors and a phone camera during pre-production. Secondly, we had the brilliant Rupert Peddle operating the Steadicam. Thirdly, it would have been so difficult to keep a boom and its shadows out of shot that mixer Filipe Pinheiro and his team didn’t even try, instead relying on lavaliers and a mic mounted on the camera.

For similar reasons, we didn’t do much lighting either; there were almost no areas of the rooms and their ceilings that didn’t come into shot at some point. In two places Stephen rigged blackout for negative fill. I then chose which of the existing ceiling lights to turn off and which to keep on, to get as much shape into the image as possible. We tried to rig a grid onto one of the ceiling lights to take it off a wall that was getting too hot, but after one take we realised that this was in frame, so instead we stuck a square of ND gel to it. We also rigged two Astera tubes in the corridor, but discovered that one of those came into frame too, so in the end a single Astera tube was the only additive lighting. The existing ceiling lights worked particularly well for a slow push-in to Alice near the end of the shot, providing her with both key and backlight from perfect angles.

Day 5

Today we shot a big scene based around a school play. Production designer Amanda Stekly had created a suitably cheesy, sparkly backdrop, and more PQA students dressed up in weird and wonderful costumes to enact snatches of a very random production called Spamlet (making it the second time this year I’ve shot “to be or not to be”, though this time was… er… a little different).

The school had a basic lighting rig already. We refocused and re-gelled some of the lights, keeping it very simple and frontal. Behind the set I put one of my old 800W Arri Lites as a backlight for the kids on stage. To one side, where Alice was standing, we used two Astera tubes, one to key her and one to backlight her. These were both set to a cool, slightly minty colour. My idea of using green for calming characters and moments hasn’t come to fruition quite as I’d planned, because it hasn’t fitted the locations and other design elements, but there’s a little hint of it here.

For the audience, Stephen rigged an Aputure 300D to the ceiling as a backlight, then we bounced the stage lighting back onto them using a silver board. We also used the school’s follow spot, which gave us some nice flares for the stressful moments later in the scene. It was daytime both in reality and in the story, but we closed the (thin) curtains and reduced the ambience outside with floppy flags so that the artificial lighting would have more effect.

We had to move at breakneck speed in the afternoon to get everything in the can before wrap time, but we managed it, finishing our first week on schedule. No mean feat.