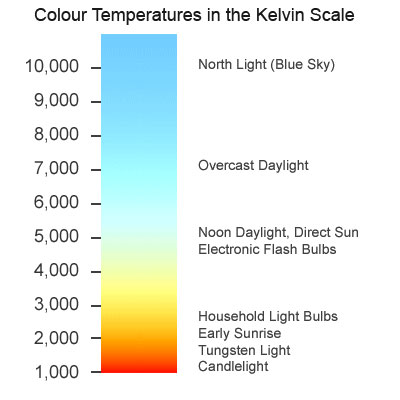

Colour temperature starts with something mysterious called a “black body”, a theoretical object which absorbs all frequencies of electromagnetic radiation and emits it according to Planck’s Law. Put simply, Planck’s Law states that as the temperature of such a body increases, the light which it emits moves toward the blue end of the spectrum. (Remember from chemistry lessons how the tip of the blue flame was the hottest part of the Bunsen Burner?)

Colour temperature is measured in kelvins, a scale of temperature that begins at absolute zero (-273°C), the coldest temperature physically possible in the universe. To convert centigrade to kelvin, simply add 273.

The surface of the sun has a temperature of 5,778K (5,505°C), so it emits a relatively blue light. The filament of a tungsten studio lamp reaches roughly 3,200K (2,927°C), providing more of an orange light. Connect that fixture to a dimmer and bring it down to 50% intensity and you might get a colour temperature of 2,950K, even more orange.

The surface of the sun has a temperature of 5,778K (5,505°C), so it emits a relatively blue light. The filament of a tungsten studio lamp reaches roughly 3,200K (2,927°C), providing more of an orange light. Connect that fixture to a dimmer and bring it down to 50% intensity and you might get a colour temperature of 2,950K, even more orange.

Incandescent lamps and the sun’s surface follow Planck’s Law fairly closely, but not all light sources rely on thermal radiation, and so their colour output is not dependent on temperature alone. This leads us to the concept of “correlated colour temperature”.

The correlated colour temperature of a source is the temperature which a black body would have to be at in order to emit the same colour of light as that source. For example, the earth’s atmosphere isn’t 7,100K hot, but the light from a clear sky is as blue as a Planckian body glowing at that temperature would be. Therefore a clear blue sky has a correlated colour temperature (CCT) of 7,100K.

The correlated colour temperature of a source is the temperature which a black body would have to be at in order to emit the same colour of light as that source. For example, the earth’s atmosphere isn’t 7,100K hot, but the light from a clear sky is as blue as a Planckian body glowing at that temperature would be. Therefore a clear blue sky has a correlated colour temperature (CCT) of 7,100K.

LED and fluorescent lights can have their colour cast at least partly defined by CCT, though since CCT is one-dimensional, measuring only the amount of blue versus red, it may give us an incomplete picture. The amounts of green and magenta which LEDs and fluorescents emit varies too, and some parts of the spectrum might be missing altogether, but that’s a whole other can of worms.

The human eye-brain system ignores most differences of colour temperature in daily life, accepting all but the most extreme examples as white light. In professional cinematography, we choose a white balance either to render colours as our eyes perceive them or for creative effect.

Most cameras today have a number of white balance presets, such as tungsten, sunny day and cloudy day, and the options to dial in a numerical colour temperature directly or to tell the camera that what it’s currently looking at (typically a white sheet of paper) is indeed white. These work by applying or reducing gain to the red or blue channels of the electronic image.

Interestingly, this means that all cameras have a “native” white balance, a white balance setting at which the least total gain is applied to the colour channels. Arri quotes 5,600K for the Alexa, and indeed the silicon in all digital sensors is inherently less sensitive to blue light than red, making large amounts of blue gain necessary under tungsten lighting. In an extreme scenario – shooting dark, saturated blues in tungsten mode, for example – this might result in objectionable picture noise, but the vast majority of the time it isn’t an issue.

The difficulty with white balance is mixed lighting. A typical example is a person standing in a room with a window on one side of them and a tungsten lamp on the other. Set your camera’s white balance to daylight (perhaps 5,600K) and the window side of their face looks correct, but the other side looks orange. Change the white balance to tungsten (3,200K) and you will correct that side of the subject’s face, but the daylight side will now look blue.

Throughout much of the history of colour cinematography, this sort of thing was considered to be an error. To correct it, you would add CTB (colour temperature blue) gel to the tungsten lamp or perhaps even place CTO (colour temperature orange) gel over the window. Nowadays, of course, we have bi-colour and RGB LED fixtures whose colour temperature can be instantly changed, but more importantly there has been a shift in taste. We’re no longer tied to making all light look white.

To give just one example, Suzie Lavelle, award-winning DP of Normal People, almost always shoots at 4,300K, halfway between typical tungsten and daylight temperatures. She allows her practical lamps to look warm and cozy, while daylight sources come out as a contrasting blue.

It is important to understand colour temperature as a DP, so that you can plan your lighting set-ups and know what colours will be obtained from different sources. However, the choice of white balance is ultimately a creative one, perhaps made at the monitor, dialling through the kelvins to see what you like, or even changed completely in post-production.