“These are small,” Father Ted once tried to explain to Father Dougal, holding up toy cows, “but the ones out there are far away.” We may laugh at the gormless sitcom priest, but the chances are that we’ve all confounded size and distance, on screen at least.

The ship marooned in the desert in Close Encounters of the Third Kind, the cliff at the end of Tremors, the runways and planes visible through the windows of Die Hard 2’s control tower, the helicopter on the boat in The Wolf of Wall Street, even the beached whale in Mega Shark Versus Giant Octopus – all are small, not far away.

The most familiar forced perspective effect is the holiday snap of a friend or family member picking up the Eiffel Tower between thumb and forefinger, or trying to right the Leaning Tower of Pisa. By composing the image so that a close subject (the person) appears to be in physical contact with a distant subject (the landmark), the latter appears to be as close as the former, and therefore much smaller than it really is.

Architects have been playing tricks with perspective for centuries. Italy’s Palazzo Spada, for example, uses diminishing columns and a ramped floor to make a 26ft corridor look 100ft long. Many film sets – such as the basement of clones in Moon – have used the exact same technique to squeeze extra depth out of limited studio space or construction resources.

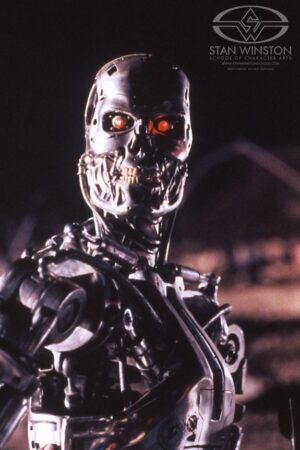

Even a set that is entirely miniature can benefit from forced perspective, with a larger scale being used in the foreground and a smaller one in the background, increasing the perceived depth. For example, The Terminator’s “Future War” scenes employ skulls of varying size, with background ruins on an even smaller scale.

An early cinematic display of forced perspective was the 1908 short Princess Nicotine, in which a fairy who appears to be cavorting on a man’s tabletop is actually a reflection in a distant mirror. “The little fairy moves so realistically that she cannot be explained away by assuming that she is a doll,” remarked a Scientific American article of the time, “and yet it is impossible to understand how she can be a living being, because of her small stature.”

During the 1950s, B movies featuring fantastically shrunk or enlarged characters made full use of forced perspective, as did the Disney musical Darby O’Gill and the Little People. VFX supervisor Peter Ellenshaw, interviewed for a 1994 episode of Movie Magic, remembered the challenges of creating sufficient depth of field to sell the illusion: “You had to focus both on the background and the foreground [simultaneously]. It was very difficult. We had to use so much light on set that eventually we blew the circuit-breakers in the Burbank power station.”

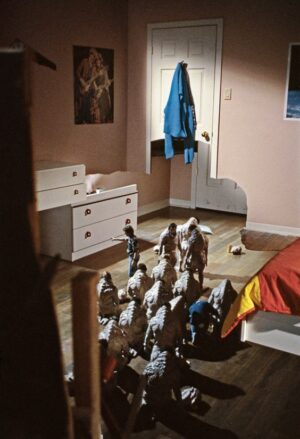

Randall William Cook was inspired years later by Ellenshaw’s work when he was called upon to realise quarter-scale demonic minions for the 1987 horror movie The Gate. Faced with a tiny budget, Cook devised in-camera solutions with human characters on raised foreground platforms, and costumed minions on giant set-pieces further back, all carefully designed so that the join was undetectable. As the contemporary coverage in Cinefex magazine noted, “One of the advantages of a well-executed forced perspective shot is that the final product requires no optical work and can therefore be viewed along with the next day’s rushes.”

A subgroup of forced perspective effects is the hanging miniature – a small-scale model suspended in front of camera, typically as a set extension. The 1925 version of Ben Hur used this technique for wide shots of the iconic chariot race. The arena of the Circus Maximus was full size, but in front of and above it was hung a miniature spectators’ gallery containing 10,000 tiny puppets which could stand and wave as required.

Doctor Who used foreground miniatures throughout its classic run, often more successfully than it used the yellow-fringed chromakey of the time. Earthly miniatures like radar dishes, missile launchers and big tops were captured on location, in camera, with real skies and landscapes behind them. The heroes convincingly disembark from an alien spaceship in the Tom Baker classic “Terror of the Zygons” by means of a foreground miniature and the actors jumping off the back of a van in the distance. A third-scale Tardis was employed in a similar way when the production wanted to save shipping costs on a 1984 location shoot on Lanzarote.

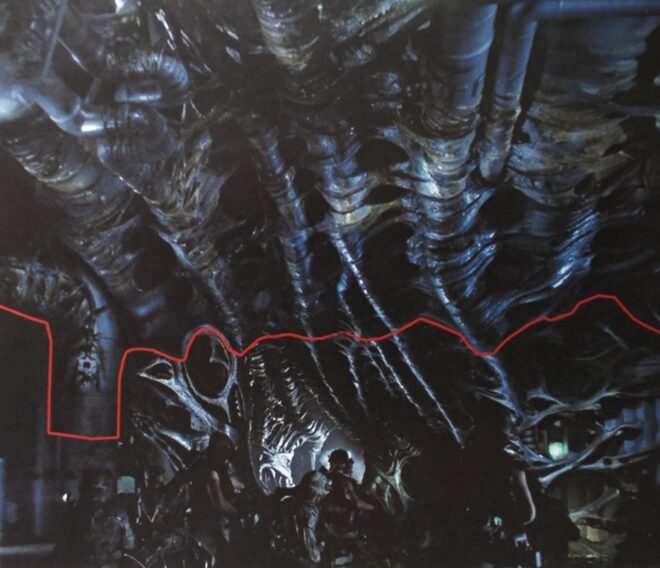

Even 60 years on from Ben Hur, Aliens employed the same technique to show the xenomorph-encrusted roof in the power plant nest scene. The shot – which fooled studio executives so utterly that they complained about extravagant spending on huge sets – required small lights to be moved across the miniature in sync with the actors’ head-torches.

The Aliens shot also featured a tilt-down, something only possible with forced perspective if the camera pivots around its nodal point – the point within the lens where the light focuses. Any other type of camera movement gives the game away due to parallax, the optical phenomenon which makes closer objects move through a field of view more quickly than distant ones.

The 1993 remake of Attack of the 50ft Woman made use of a nodal pan to follow Daniel Baldwin to the edge of an outdoor swimming pool which a giant Daryl Hannah is using as a bath. A 1/8th-scale pool with Hannah in was mounted on a raised platform to perfectly align on camera with the real poolside beyond, where Baldwin stood.

The immediacy of forced perspective, allowing actors of different scales to riff off each other in real time, made it the perfect choice for the seasonal comedy Elf. The technique is not without its disadvantages, however. “The first day of trying, the production lost a whole day setting up one shot and never captured it,” recalls VFX supervisor Joe Bauer in the recent documentary Holiday Movies That Made Us.

Elf’s studio, New Line, was reportedly concerned that the forced perspective shots would never work, but given what a certain Peter Jackson was doing for that same studio at the same time, they probably shouldn’t have worried.

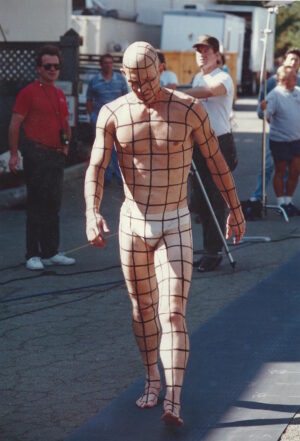

The Lord of the Rings employed a variety of techniques to sell the hobbits and dwarves as smaller than their human friends, but it was in the field of forced perspective that the trilogy was truly groundbreaking. One example was an extended cart built to accommodate Ian McKellen’s Gandalf and Elijah Wood’s supposedly-diminutive Frodo. “You could get Gandalf and Frodo sitting side by side apparently, although in fact Elijah Wood was sitting much further back from the camera than Gandalf,” explains producer Barrie Osborne in the trilogy’s extensive DVD extras.

Jackson insisted on the freedom to move his camera, so his team developed a computer-controlled system that would correct the tell-tale parallax. “You have the camera on a motion-controlled dolly, making it move in and out or side to side,” reveals VFX DP Brian Van’t Hul, “but you have another, smaller dolly [with one of the actors on] that’s electronically hooked to it and does the exact same motion but sort of in a counter movement.”

Forced perspective is still alive and kicking today. For Star Wars Episode IX: The Rise of Skywalker, production designer Kevin Jenkins built a 5ft sand-crawler for shooting in the Jordan Desert. “It was placed on a dressed table at height,” he explained on Twitter, “and the Jawa extras were shot at the same time a calculated distance back from the mini. A very fine powdery sand was dressed around for scale. We even made a roller to make mini track prints! Love miniatures :)”