Last weekend saw many of the crew of Above the Clouds reunite to shoot the remaining scenes of this comedy road movie. Principal photography was captured on an Alexa Mini during summer 2016 on location in Kent, on the Isle of Skye, and at Longcross Studio in Buckinghamshire, with additional location shooting on a Blackmagic Micro Cinema Camera in October.

Last weekend saw many of the crew of Above the Clouds reunite to shoot the remaining scenes of this comedy road movie. Principal photography was captured on an Alexa Mini during summer 2016 on location in Kent, on the Isle of Skye, and at Longcross Studio in Buckinghamshire, with additional location shooting on a Blackmagic Micro Cinema Camera in October.

The outstanding scenes were to be photographed on stage, at Halliford Studio in Shepperton, this time on an Arri Amira. The Amira uses the same sensor as the Alexas, allowing us to match the look from principal photography in the most cost-effective way. With the addition of a Premium license, the camera is capable of the same ProRes 4444 recording codec as the Alexas too. As per last summer, our glass was a set of Arri/Zeiss Ultra Primes, with a half Soft FX filter to take the digital edge off.

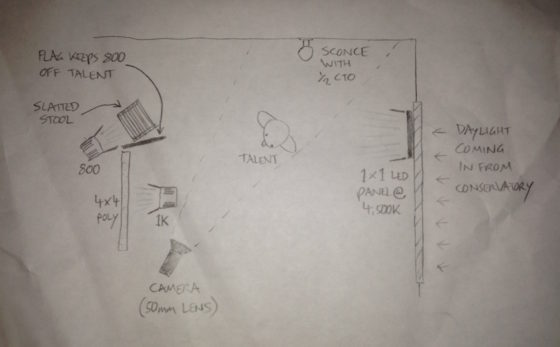

Director Leon Chambers designed and built the set himself, sending me photos of a scale model well in advance. He was also specific about certain lighting cues and states that were required across the two sets and six scenes we would be recording to complete the movie. Based on this information, I concocted a lighting plan, which I communicated to Halliford’s in-house gaffer Micky Reeves by Photoshopping stock images of lamps onto Leon’s set model photos.

Last Saturday was devoted to pre-lighting the sets, mainly the kitchen, while construction work continued on the second set.

Day 24 / Sunday

Day 24 / Sunday

We begin with a morning scene. A 5K fresnel serves as a low sun, streaking across the back wall of the set (see my post about lighting through windows). Even with this direct light four stops over, the natural bounce off the set isn’t enough to bring actor Philip Jackson – with his back to the window – up to key. Micky rigs a Dedo firing into a soft silver bounce just out of frame to solve the problem.

Also coming through the window are two 4×4 kinos, rigged on goalposts above the window. Their daylight tubes reflect off the blinds, serendipitously creating the illusion of a blue sky “outdoors”, where in fact there is only a wall and a white backdrop.

Philip exits into the hallway and disappears from view, supposedly to go out through the front door. No door exists. Instead there is a flag which spark Amir Moulfi rotates in front of a 2K, creating a momentary oblong of light in which Philip’s shadow appears.

The next scene follows on from an exterior captured last October at dusk, when the natural light was soft, flat and cool in colour, cheated even cooler with the white balance. This failing daylight is to be the only source of illumination now in the kitchen set, until Philip enters and turns on the lights. This is the main reason that the daylight 4×4 kinos outside the window were rigged. A third kino from the direction of the front door is added, plus a small LED reporter light to pick an important prop out of the shadows.

Lead actress Naomi Morris enters, silhouetted against the windows. Then Philip enters and hits the lights. Simultaneously, Amir flips a breaker on a lunchbox, activating a hanging practical fixture above the breakfast bar and the 5K which that practical motivates.

Generally I don’t like toplight. It throws the eyes – those windows to the soul… or windows to the performance – into shadow. But with the hanging practical in shot, whatever I was going to use to beef it up had to be somewhat toppy or it wouldn’t make sense. I considered space-lights and Jem balls, but in consultation with Micky I ultimately picked a 5K with a chimera, coming in at a 45 degree back/toplight angle. As you can see from the photos, this looks almost comically large. But large and close means soft, which is what I want. It had to be soft enough to wrap both actors when they faced each other across the bar.

Generally I don’t like toplight. It throws the eyes – those windows to the soul… or windows to the performance – into shadow. But with the hanging practical in shot, whatever I was going to use to beef it up had to be somewhat toppy or it wouldn’t make sense. I considered space-lights and Jem balls, but in consultation with Micky I ultimately picked a 5K with a chimera, coming in at a 45 degree back/toplight angle. As you can see from the photos, this looks almost comically large. But large and close means soft, which is what I want. It had to be soft enough to wrap both actors when they faced each other across the bar.

But why such a large lamp? Why not use a 2K, like Micky suggested yesterday? Bitter experience has always taught me to go with a bigger unit than you think you need, particularly if you’re softening it, and particularly if it’s going to take a while to rig. (The 5K was hung from another goalposts set-up.) We ended up dimming the 5K to 50% and scrimming it down a stop and a half. But having too much light like that is easy to deal with. If we had put up a 2K and it wasn’t bright enough, we would have to have taken the whole thing down and re-rigged with a 5K. And even if the 2K had seemed sufficient to begin with, blocking can often take actors into unexpected, dark corners of the set. Being able to turn up a dimmer a couple of notches to handle that kind of situation is very useful.

Besides the 5K, there are a few other sources playing: some 300W hairlights, a pup bouncing off the side of a cupboard to bring up the area around the cooker, a China ball in the hallway, and Leon’s Rosco LitePads serving as practical under-cabinet down-lighters.

Day 25 / Monday

I probably shouldn’t say what today’s set is, because it’s a little bit of a spoiler. There are some lighting similarities to the kitchen: again we have a character flicking a light switch, bringing on two hanging overhead practicals and a 2K with a chimera to beef them up.

I probably shouldn’t say what today’s set is, because it’s a little bit of a spoiler. There are some lighting similarities to the kitchen: again we have a character flicking a light switch, bringing on two hanging overhead practicals and a 2K with a chimera to beef them up.

A practical lamp on a desk was supposed to be turned on during the scene as well, but we all forget until it’s too late. It would have bounced off the desk and given Philip a little eye-light, and at first I regret losing this. But soon I realise that it is more appropriate for the scene not to have that level of refinement, for the lighting to be a little raw. The toppy, “broken key” angle of the chimera’s light works well for this tone too.

We wrap just before noon, releasing Naomi to high-tail it to Oxford to appear on stage in a musical this evening. Eventually there will be second-unit-style GVs and establishing shots to do, but there will only be three or four of us for that. For the cast and most of the crew, today brings Above the Clouds to an end, eight months after the camera first rolled.

See all my Above the Clouds posts here, or visit the official website.