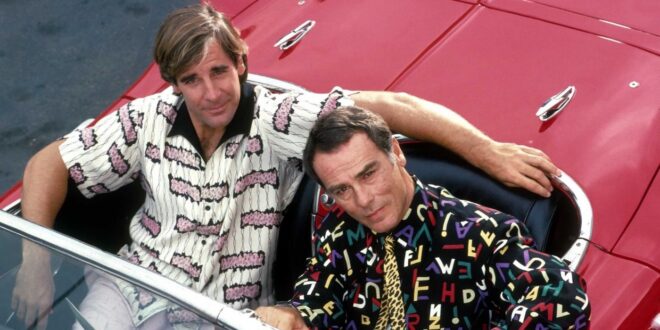

I have been a huge fan of the British sci-fi sitcom Red Dwarf since the age of 12 or 13. The show has undergone many changes over the years, and every fan has their own view about which era is the best, but for me seasons V and VI will always be my favourites. I discovered the show during season V and I remember the huge anticipation for the next season. During this time the show’s production values were very high but it was still extremely funny, with the main characters all well established and well rounded.

So I was delighted to come across Joe Nazzaro’s book The Making of Red Dwarf in a charity shop recently. It focuses on the production of the series’ most lauded episode, the International Emmy-winning “Gunmen of the Apocalypse” from 1993. The episode sees mechanoid Kryten deliberately contract a computer virus in order to save the Red Dwarf posse, and their efforts to help him battle the infection within the framework of a Wild West VR game representing his consciousness.

What I find fascinating is that the series, at that time at least, was made in such a different way to modern high-end TV or film, following instead the multi-camera sitcom pattern of rehearsing all week and recording in the evening on Saturday.

The cycle began on a Sunday, with production designer Mel Bibby removing the previous episode’s sets from Stage G at Shepperton and installing the new ones.

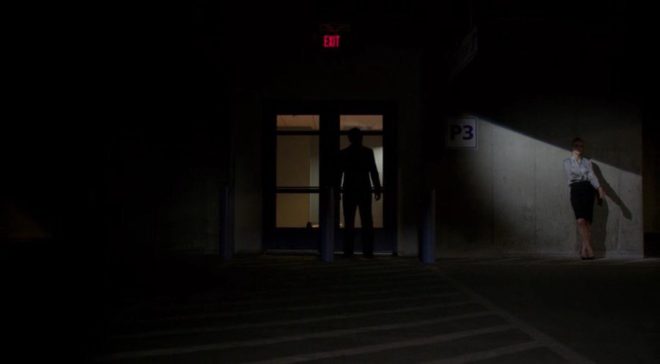

On Monday the director, writers and cast rehearsed on the set while certain crew members travelled to location – the Laredo Western Club in Kent – to pre-rig. A British sitcom at this time had no director of photography; instead the camera angles were chosen purely by the director and technically executed under the purview of the camera supervisor, while illumination was provided by the lighting director, in this case John Pomphrey. His work at Laredo included putting warm lights inside the buildings to match the look of the interiors which he planned for the studio.

Pomphrey lit a lot of rock and pop shows, and was inspired by concert lighting for such bands as Iron Maiden:

“If you look at them they’re into the same colours I am: oranges, deep blues; powerful colours. I don’t believe in understating something, because you’re generally watching it on a small screen in a well-lit room, so you’ve got to overstate the colours. In the cinema, you can get away with subtle tones, but I don’t think you can on this show… I’m a frustrated cinematographer: I want to make ‘Aliens’.”

Tuesday was the location shoot, conducted with multiple cameras (though not for every set-up) as director Andy DeEmmony worked through his storyboards. At this time all UK TV was 4:3 standard definition. While a high-end drama would have used 16mm film, most shows, including Red Dwarf, were captured on a tape format like Betacam SP. “Gunmen of the Apocalypse” saw the series make rare use of a crane, and behind-the-scenes photos also show at least one HMI shining through a diffusion frame. It was common practice at this time to use large HMIs to fill in shadows on sunny day exteriors.

On Wednesday rehearsals continued on stage, culminating in a tech run during which camera supervisor Rocket previewed shots using the classic hand-framing method. In the evening the production team convened to discuss the next episode, “Polymorph II: Emohawk”.

Thursday was known as the Pre-VT day: the day when all scenes too complex to shoot in front of the live audience must be recorded. With “Gunmen” this meant scenes inside the Last Chance Saloon which required such camera tricks as pulling knives out of antagonist Jimmy’s jacket on nylon wires so that in reverse it looked like the knives were pinning him to the wall, Rimmer’s bar fight with four cowboys, and a scene aboard the Simulant ship which is the source of Kryten’s infection.

Pomphrey would communicate by radio with Dai Thomas, who spent studio days in a darkened cabin operating a lighting desk while watching the action on two monitors.

Friday saw more rehearsals, while Tuesday and Thursday’s footage was edited to show to the live audience tomorrow.

Saturday began with blocking and camera rehearsals, before the doors opened to the public at 7pm and recording commenced at 7:30.

It seems that Shepperton Stage G was not equipped with a gallery like a dedicated TV studio; instead, vision mixing was done from the scanner – an outside broadcast truck. For those who don’t know, vision mixing is live editing, cutting from one camera to another in real time as a production assistant calls the shots from the director’s camera script. Elsewhere in the scanner, an engineer monitored the images, doing something akin to the job of a modern DIT, adjusting colours, sharpness and even remotely controlling the cameras’ irises. (Zoom and focus were controlled by the camera operators.)

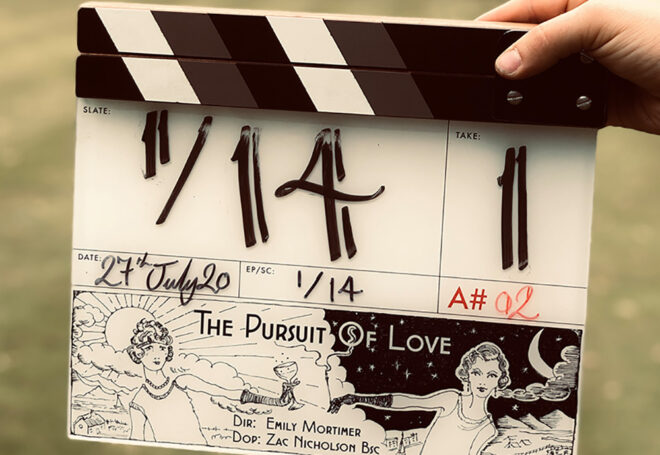

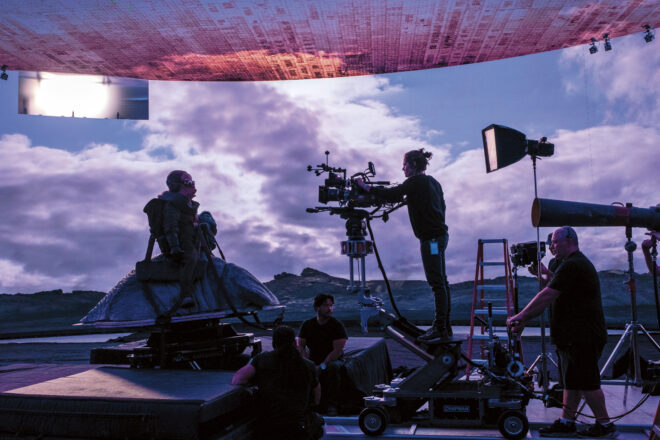

It’s a testament to all concerned that the show looked so cinematic despite being made this way. Later seasons became even more cinematic, doing away with the live audience for a little while, then bringing it back and later kick-starting Ed Moore BSC’s career when he shot seasons XI and XII beautifully. By this time the show was produced by Dave (a channel named, appropriately enough, after Red Dwarf‘s slobbish hero Dave Lister). It was now captured in HD, on Red cameras of some flavour if I remember rightly, with a focus puller for each one and a more film-like crew structure .

It’s unclear at present if any more seasons will follow 2020’s “The Promised Land”, but if they do I’m sure the series will continue to evolve and embrace new technologies and working practices. Which is a very dull way to end a post about a very funny show, so instead I’ll leave you with one of my favourite jokes from the series, which will make no sense whatsoever unless you remember the set-up.

Kryten, no kitchen appliance should give a human being a double polaroid.