After seeing Barry Lyndon (1975) on the big screen this week, I felt compelled to write a blog post about its cinematography. But what aspect of the cinematography? The painterly look? The many zooms? The use of natural light?

After seeing Barry Lyndon (1975) on the big screen this week, I felt compelled to write a blog post about its cinematography. But what aspect of the cinematography? The painterly look? The many zooms? The use of natural light?

What I knew for certain is that I should definitely not write about the entirely candlelit scenes lensed on f/0.7 Nasa glass, because everyone knows that story. However, reading the vintage American Cinematographer article and some other material, I found the details surrounding this groundbreaking use of high-speed lenses so interesting that I decided to do it anyway.

The Vision

Barry Lyndon is the 18th century tale of a low-born Irishman who strives – through various misadventures, and ups and downs of fortune – to become a gentleman. The key visual influence of director Stanley Kubrick and DP John Alcott, BSC were the great painters of the story’s era, such as Vermeer.

Next week’s post will look at this painterly influence in Barry Lyndon more closely, but for now the important thing is the use of candlelight on those classical canvases, and Kubrick’s desire to replicate that look. According to lens expert Ed DiGuilio, who was tasked with adapting the f/0.7 glass for Lyndon, Kubrick “wanted to preserve the natural patina and feeling of these old castles at night as they actually were”.

Typically in movies, a candle in frame may motivate the lighting, but most of the illumination on the actors actually comes from an orange-gelled lamp just out of frame. Kubrick wasn’t interested in shooting Lyndon that way. He wanted all the light in those night interior scenes to genuinely come from the candles themselves.

The Problem

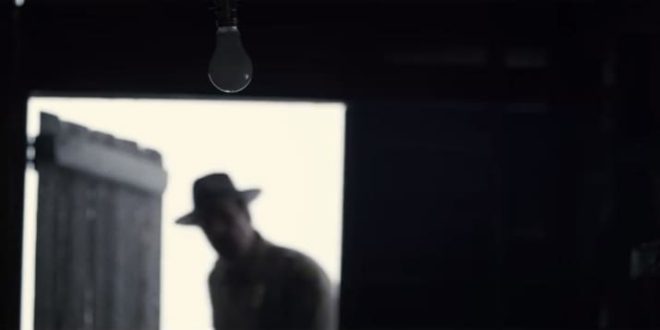

How much light does a candle shed? Conveniently, there is a unit of illumination called the foot-candle. One foot-candle is the amount of light received from a standard candle one foot away. Without going into the detail of what a “standard” candle is, it is enough for our purposes to say that the scene below has a key light of about three foot-candles…

… because there are three candles, about a foot away from the actor’s face. (The level of your key light, and consequently where you set your aperture, is almost always measured at your subject’s face, as that is usually the focus of the shot and the most important thing to get correctly exposed. This is why we DPs are always waving light meters in actors’ faces.)

If we look at an exposure table, such as this one, we can see that a three foot-candle key can be correctly exposed with an aperture of T1.4 and an EI (exposure index) of 800. Today that would be no problem, with many digital cameras having a native EI of 800, and the availability of fast lenses like Zeiss Master Primes and Super Speeds.

In the mid-seventies however, long before the advent of digital cameras, things were not so simple. Kubrick and Alcott had little choice but to shoot on Eastman Kodak 100T 5254. Those first three digits denote the film stock’s exposure index: 100. Alcott pushed the stock (brought the brightness up during processing) one stop, re-rating it to an EI of 200. But it still needed four times more light, or two stops more light than our modern-day Alexa or Red. (Check out my post on f-stops and T-stops if you’re getting lost.)

If we’re losing two stops on the EI, we need to gain two stops on the aperture to compensate. And two stops up from T1.4 is T0.7. You may notice that T0.7 isn’t on that table I linked to. This is because a lens with such a large relative aperture pretty much doesn’t exist.

Pretty much…

The Solution

Kubrick obsessively researched the problem. He eventually discovered that Nasa had commissioned Carl Zeiss to build ten Planar 50mm f/0.7 stills lenses in the sixties, which were used to take photos of the dark side of the moon. (I was unable to find out the T-stop of these lenses, but I’ll assume it was close enough to T0.7 for it to make little difference to my calculations above.) The developments leading to these lenses stretched back through Nazi military applications during WW2 all the way to the late Victorian era, when the double-Gauss cell at the core of the lenses was first invented.

Kubrick obsessively researched the problem. He eventually discovered that Nasa had commissioned Carl Zeiss to build ten Planar 50mm f/0.7 stills lenses in the sixties, which were used to take photos of the dark side of the moon. (I was unable to find out the T-stop of these lenses, but I’ll assume it was close enough to T0.7 for it to make little difference to my calculations above.) The developments leading to these lenses stretched back through Nazi military applications during WW2 all the way to the late Victorian era, when the double-Gauss cell at the core of the lenses was first invented.

Anyway, Kubrick promptly bought three of the Zeiss Planars. He liked to own equipment himself, rather than hire it in, and to this end he had also purchased at least one Mitchell BNC camera. As befits Kubrick’s perfectionism, these were perhaps the world’s most precisely engineered cameras, previously used for special effects work.

This is where Ed DiGuilio comes in: “[Kubrick] called one day to ask me if I thought I could fit a Zeiss lens he had procured… to his BNC.” It wasn’t simply a case of the f/0.7 glass having the wrong mount. The rear element was so large and needed to be so close to the film plane that DiGuilio had to extensively modify the camera, literally cutting parts out of it.

Once this was done, extensive testing ensued. The focus scale (distances marked on the barrel) had to be calibrated from scratch, and indeed the focus ring was re-engineered to allow the precision focusing that the lens’ tiny depth of field would require. Whereas the focus ring on a stills lens will turn about 90° to go from infinity to close focus, and the ring on a cine lens might turn 270°, the rings on these unique Planars now turned a whopping 720° – two whole revolutions!

50mm is a very useful lens length for close-ups, but Kubrick understandably wanted a wider option as well. Accordingly, DiGuilio located an adapter designed to adjust the throw of cinema projector lenses. Mounted onto one of the 50s, it gave an effective focal length of 36.5mm with only very minor light loss. A 24mm version was also tested, but Kubrick disliked the amount of distortion in its images, and rejected it.

The Execution

The colour brown and the trousers of Doug Milsone, Barry Lyndon‘s focus puller, cannot have been strangers to each other. Imagine trying to hold focus on this dolly-back at f/0.7!

By my calculations (which were difficult, because most depth of field tables/calculators don’t go to f/0.7!) an MCU on Kubrick’s 50mm Planar with the subject at 2.5m (8.2ft) and the iris wide open would have had a depth of field of about 43mm (1.7″). To get this same depth of field at f2.8, a popular working stop for cinematographers today, the subject would have to be just 1m (3.3ft) from the sensor plane, which would be a biggish close-up. And remember that focus monitors, peaking and Cine Tape did not exist in the seventies.

To give Milsone a fighting chance, a unique system of focus assist was developed. While the main camera shot an actor from the front, a CCTV camera captured them in profile. This profile image was piped to a monitor, over which a grid was placed. This grid was marked off with distances so that Milsone could see how much the actor had moved by, far more accurately than judging it by eye from beside the lens.

To give Milsone a fighting chance, a unique system of focus assist was developed. While the main camera shot an actor from the front, a CCTV camera captured them in profile. This profile image was piped to a monitor, over which a grid was placed. This grid was marked off with distances so that Milsone could see how much the actor had moved by, far more accurately than judging it by eye from beside the lens.

Another problem thrown up by the low-light cinematography was with the viewfinder. Interestingly, the Mitchell BNC was a non-reflex camera, meaning that it didn’t have a mirror on the shutter, reflecting the image to the viewfinder when the shutter was closed. Instead, the camera body racked over to one side to allow the viewfinder to get an image during line-ups and rehearsals, and when it was actually rolling the operator got their images from a side viewfinder with its own lens – just like in a disposable 35mm stills camera. The original prism-based viewfinder on Kubrick’s Mitchell BNC suffered from far too much light loss for a candlelit image to be visible through it, so it was replaced with a mirror-based viewfinder adapted from a Technicolor camera.

The shots resulting from all of these technical challenges are quite soft to the modern eye, but I think that only adds to their beauty. Barry Lyndon captured the exquisite fragility of candelight, and 42 years on the images are still unique and captivating.

I won my first DVD player in a trailer competition on a sort of YouTube forerunner site in December 2000. Over the next decade I was entertained and educated by many extras-packed Digital Versatile Discs. Now, of course, physical media is a thing of the past, but many of the anecdotes I heard in DVD commentaries have stuck in my mind. Some have even helped me on set when facing a new situation.

I won my first DVD player in a trailer competition on a sort of YouTube forerunner site in December 2000. Over the next decade I was entertained and educated by many extras-packed Digital Versatile Discs. Now, of course, physical media is a thing of the past, but many of the anecdotes I heard in DVD commentaries have stuck in my mind. Some have even helped me on set when facing a new situation.

Although the DVD menu lists it as a director’s commentary, Bryan Singer in fact pairs up with his DP Newton Thomas Sigel for this track. Sigel discusses the importance of building practicals into the sets to enhance realism and flexibility of shooting. He explains how he colour-coded certain scenes so that the audience would more readily understand where they were during the fast-paced action sequences; for example, the corridors of the Alkali Lake bunker were lit with a moss green.

Although the DVD menu lists it as a director’s commentary, Bryan Singer in fact pairs up with his DP Newton Thomas Sigel for this track. Sigel discusses the importance of building practicals into the sets to enhance realism and flexibility of shooting. He explains how he colour-coded certain scenes so that the audience would more readily understand where they were during the fast-paced action sequences; for example, the corridors of the Alkali Lake bunker were lit with a moss green.

The departure of director David Fincher from Alien 3 – under a cloud of studio interference and re-edits – is an infamous part of movie lore. Less well known is that the director of photography changed a week into shooting, after original DP Jordan Cronenworth (of Blade Runner fame) fell ill. Alex Thompson stepped in, and his humble, soft-spoken observations are spliced with other crew and cast members to form the commentary track on the Alien Quadrilogy boxset version of this film. Throughout the track he explains how he created the cool, toppy look of the prison’s communal areas, the dark, shadowy environs of the basements, and the hot, hellish feel of the lead-works. There are some interesting remarks about practicals too, such as the deliberate use of mismatched, low-CRI fluorescent tubes to give the canteen a run-down look, and tips for creating convincing firelight flicker.

The departure of director David Fincher from Alien 3 – under a cloud of studio interference and re-edits – is an infamous part of movie lore. Less well known is that the director of photography changed a week into shooting, after original DP Jordan Cronenworth (of Blade Runner fame) fell ill. Alex Thompson stepped in, and his humble, soft-spoken observations are spliced with other crew and cast members to form the commentary track on the Alien Quadrilogy boxset version of this film. Throughout the track he explains how he created the cool, toppy look of the prison’s communal areas, the dark, shadowy environs of the basements, and the hot, hellish feel of the lead-works. There are some interesting remarks about practicals too, such as the deliberate use of mismatched, low-CRI fluorescent tubes to give the canteen a run-down look, and tips for creating convincing firelight flicker.